Spatial planning: the good, the bad and the needy

Unbalanced regional development is a common economic concern. It arises from ‘clustering’ of companies and resources, compounded by higher benefit-to-cost ratios for infrastructure projects in well developed regions. Government efforts to redress this balance have had mixed success. Dr Rupert Booth, Senior Adviser, proposes a practical programme to develop a National Spatial Strategy and adjust public investment guidelines to ease its implementation.

Unbalanced economic development is a perennial problem and it seems to be the case that ‘to those that have, more shall be given’, as a reinforcing feedback loop takes hold, in terms of both positive and negative regional outcomes. Such a loop arises from agglomeration effects, whereby a company benefits from being located near another, similar firm, often in a city. This leads to a clustering of companies in a particular industry sector, or even in most sectors. The underlying contributing factors include access to an already developed workforce, knowledge spillovers and collaboration, access to an existing network of suppliers or customers, or simply economies of scale in the use of supporting infrastructure, such as local schools for employees’ children or fast rail links.

In some cases, development authorities consciously develop industrial clusters to accelerate economic growth. One example is the EU’s sponsoring of agri-tourism to increase prosperity in rural locations.1 But more commonly this agglomeration presents itself as a problem, with a prosperous nucleus and a deprived periphery. This can be avoided, or at least offset, by the conscious adoption of a national spatial strategy (NSS).

Successes and failures

One example of co-ordinated spatial development is in the Netherlands, a small country that has planned for compact cities that resist suburban sprawl and encourages public transport and active travel. Given its low-lying territory, it has long been aware of water management and the need for resilient infrastructure, and this is being augmented by a commitment to sustainable development. Key to this is the adoption of transport-oriented development, and integrated land use to encouraged mixed-use developments that reduce the need for essential transport. All this is achieved with a tiered governance structure that encourages local participation in planning and zoning and avoids over-centralisation.

Another successful European example, this time in a large country, is in Germany. Here, spatial development has avoided wide regional disparities in wealth (although the reunification process of East and West Germany has created its own imbalances). Most of the planning has been delegated to Germany’s 16 Länder, although the federal government still sets the planning framework and ensures consistency with the EU spatial development policies (although note that a common European perspective is still work in progress).2

Outside Europe, one of the more proactive spatial development policies can be found in the Republic of Korea. The policy has evolved along with the nation, shaped by a combination of rapid industrialisation, urbanisation, economic development, and the need to address social and environmental challenges. Until the 1960s the priority was post-war reconstruction, and this was followed by industrialisation and urbanisation in the 1970s, leading to new town development and regional planning in the 1980s to address the over-development of the Seoul Metropolitan Area. The spatial plan led to the creation of satellite cities with connecting transportation links aimed at distributing the population and economic activities across a wider region. This was not entirely successful and in the new millennium Seoul still suffered from overpopulation, congestion and pollution, leading to new policies based on green growth and sustainability. Today’s focus is on smart cities using information technologies to support sustainability and resilience. The current national spatial plan is the 4th Comprehensive National Territorial Plan (2020–40). A key feature of the South Korean approach is the centralisation of policy and decision-making, which is very different from the European approach of working through multiple layers of government.

Not all NSSs are successful at the first attempt. Ireland launched its 20-year NSS in 2002 to widespread acclaim, but it did not last. This was for several reasons: it tried to be all things to all stakeholders and was not selective; the economic boom at the time led to unplanned development; and there was insufficient political sponsorship to integrate it with other relevant policies such as those relating to housing. Ireland is now undergoing another attempt at a national planning framework with Project Ireland 2040, launched in 2018.

In the UK the picture is mixed. Northern Ireland, Wales and Scotland have spatial plans, but England does not—and this is discussed further in the box below.

The English experience

A presentation at the Regulatory Policy Institute on housing policy1 proved to be an opportunity to ask an expert panel whether a NSS would work for England and help to resolve the housing crisis. The unanimous answer was ‘no’, not least because local political pressures would prevent effective implementation. Poor historical experience of spatial planning was also cited, when a failure to reinforce Birmingham infrastructure in the 1960s to deal with ‘congestion’ led to the redirection of industrial investment to Northern England and a decline of the city in the 1970s. Despite this pessimism, it remains the fact that regional imbalances in England have not been effectively addressed, despite this being a priority of both the previous and current governments. The latter has recognised that building more houses to resolve a housing crisis is not enough, and has promised to implement an ‘industrial strategy’. This would be cornerstone of a NSS—but there have been four such strategies in the past 14 years,2 which is hardly a good basis for long-term planning.

So what does England currently have in place of a NSS? It has a National Planning Policy Framework, with each local authority expected to produce Local Plans and Local Transport Plans. In theory, these could link together, but there is no mechanism to ensure that they do. In practice, the Local Plans are too granular for national or even regional spatial planning, although they do coordinate with Local Enterprise Partnerships. Until 2012 a set of broader planning agencies, the Regional Development Agencies, did fulfil the regional planning role, but these were abolished as part of cost-cutting measures without a direct replacement.

In conclusion, despite the benefits of a NSS for England, there is a need to start almost from scratch.

1 Annual Competition and Regulation Conference 2024, 9 September 2024, Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford.

2 These four strategies were: the sector-specific strategies of the Coalition government of 2010–15; the May industrial strategy of 2017 with ‘grand challenges’; the 2021 ‘Plan for growth’; and the priority given to net zero and decarbonisation from 2022 onwards. In October 2024 a consultation was launched on ‘Invest 2035’, the UK’s ‘modern industrial strategy’. It covers ten years and refers to eight growth-driving sectors (Advanced Manufacturing, Clean Energy Industries, Creative Industries, Defence, Digital and Technologies, Financial Services, Life Sciences, and Professional and Business Services), and emphasises building strong trading relations. See Department for Business and Trade (2024), ‘Invest 2035: the UK’s modern industrial strategy’, 14 December.

Creating the strategy

Below I outline a process for developing a NSS for a modern industrial state or region that already has an inventory of physical assets and available skills. There will almost certainly have been prior work, leading to a national or regional economic strategy, that has analysed relative national advantages in promising sectors and proposed future investments in these sectors through either public ‘seed-corn’ financing or facilitated private investment. If such an economic plan does not exist then proposing a spatial strategy is premature, as the economic plan would set out basic planning parameters such as population growth, housing requirements, industrial zoning needs, environmental pressures and necessary transport capacities. This economic plan would also forecast expected Gross Value Added (GVA)3 growth and the fiscal demands on the state for infrastructure provision, to be paid for from taxation revenue and loan finance, with perhaps the possibility of private finance.

Once there is such an economic plan, the spatial plan can follow. The aims and objectives should be stated, although the general aim is typically to create a polycentric region with particular areas focusing on different clusters, with good connectivity to neighbouring regions or nations. This will then lead to a proposed spatial structure, taking account of existing settlements with some modifications for growth and rehabilitation, which is then the basis for the planning of housing and enhanced transport and digital links. This will ensure that there is affordable housing close (in terms of commuting time) to the expected jobs, while enabling remote working where possible. There will be a need to plan for rural/urban integration to tie in local development to prosperous urban centres. Provision of enhanced energy, water and waste facilities will be required, along with plans for resilience given the certainty of climate change. Cultural facilities are also important, since skilled workers must be persuaded to locate to developing regions, and consideration of social cohesion is crucial, to ensure that the accelerated plans for development do not leave marginalised groups behind. Last but not least are the consultation and governance arrangements, because resistance to change is inevitable.

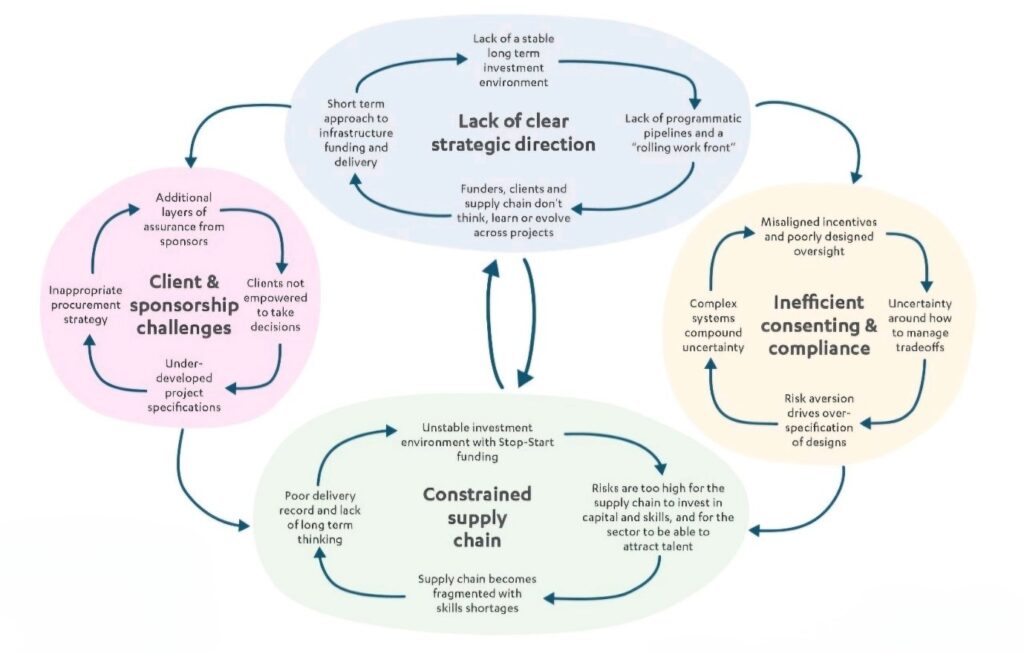

A related issue is capacity building and the need to ask: ‘Is there the infrastructure to build the infrastructure?’ Large-scale developments, of new towns, for example, require a civil engineering supply chain and any weakness will affect the implementation of the NSS. The UK has problems in this regard, and the National Infrastructure Commission has provided a systemic review, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 System analysis of UK infrastructure obstacles

Many of the above issues will not be unique to the UK, and the NSS needs to anticipate them if its implementation is not to be frustrated or delayed. Nor are constraining issues confined to engineering; local authority olanning capacity can also act as a bottleneck.

Investment appraisal

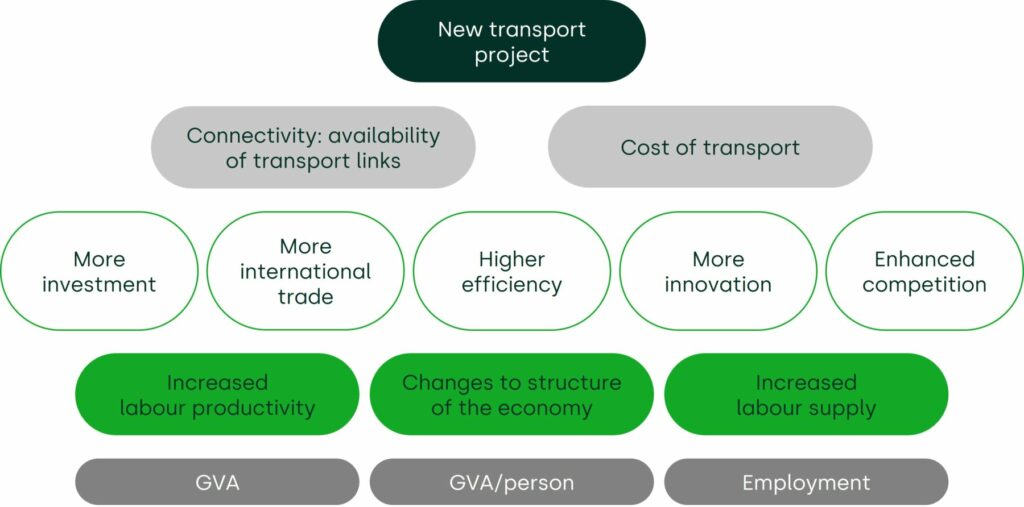

All of the above requires not only planning but also appraisals of the necessary investments. Simple cost–benefit analysis of public investments, based on welfare economics leading to a benefit–cost ratio (BCR), may not capture the nuances of long-term transformational investments, where entire zones are being re-developed. Figure 2 provides a summary of the potential factors contributing to the wider economic benefits of a transport project.

Figure 2 Wider economic benefits of transport development

Source : Oxera (2014), ‘Deep impact: assessing wider economic impacts in transport appraisal’, Agenda, November.

Appraisals of spatial development projects can be further complicated by theoretical questions surrounding the cost of land, which may not have a current market value. Economically, the land should be included in the appraisal at opportunity cost, but this cost may depend on its permitted use, which is an endogenous and discretionary factor in the scheme.

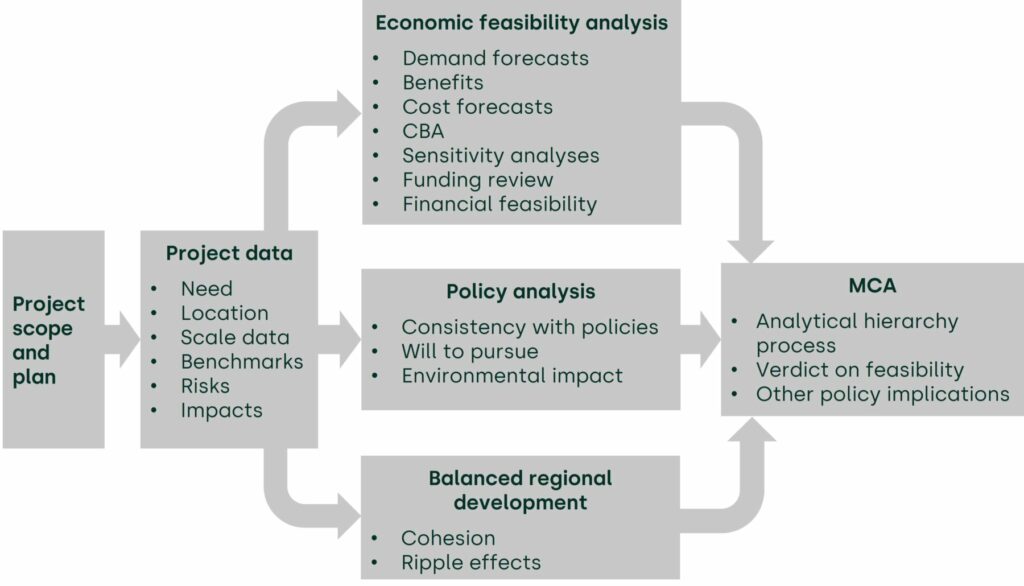

It may be that there is a need to include non-monetisable factors in the analysis, including the opinions of key experts. This can be done using multi-criteria analysis (MCA), and analytic hierarchy processing (AHP) provides one widely adopted method to do this. Figure 3 shows how AHP has been used for this purpose, based on Korean practice.

Figure 3 Use of multi-criteria analysis

Note that this process explicitly considers balanced regional development as a factor to be included in the MCA. This provides an explicit redress of the tendency of cost–benefit analysis to favour already well-developed regions because of their higher BCRs; this adjustment is more effective if there is a NSS against which to measure the conformance of the proposed scheme.

A way forward

Unbalanced regional development is a root cause of many ills, including income inequality, migration leading to over- or under-population, and social tensions. These can be mitigated by thoughtful spatial planning supported by economic appraisal to prove the financial viability of a proposed plan.

1 See European Cluster Collaboration Platform, ‘EU RURAL TOURISM: open call for tourism SMEs’, opportunity.

2 Schön, K.P. (2018), ‘European Spatial development policy’, Academy for Territorial Development in the Leibnitz Association, original translation from German.

3 GVA is the sum of Gross Domestic Product and product subsidies, less taxes. The two are closely related: GVA focuses on production, and GDP considers the value of products and services consumed.

Related

Blending incremental costing in activity-based costing systems

Allocating cost fairly across different parts of a business is a common requirement for regulatory purposes or to comply with competition law on price-setting. One popular approach to cost allocation, used in many sectors, is activity-based costing (ABC), a method that identifies the causes of cost and allocates accordingly. However,… Read More

The European growth problem and what to do about it

European growth is insufficient to improve lives in the ways that citizens would like. We use the UK as a case study to assess the scale of the growth problem, underlying causes, official responses and what else might be done to improve the situation. We suggest that capital market… Read More