Stepping on the gas: European emergency measures to deal with high energy prices

High gas and electricity prices across Europe have raised urgent concerns and started a debate about possible ways to mitigate the impacts on consumers. Countries have adopted a variety of national measures, which can be broadly classified under four categories: retail market interventions, wholesale market interventions, security of supply interventions, and energy demand reduction. What are their merits and trade-offs from an economic perspective?

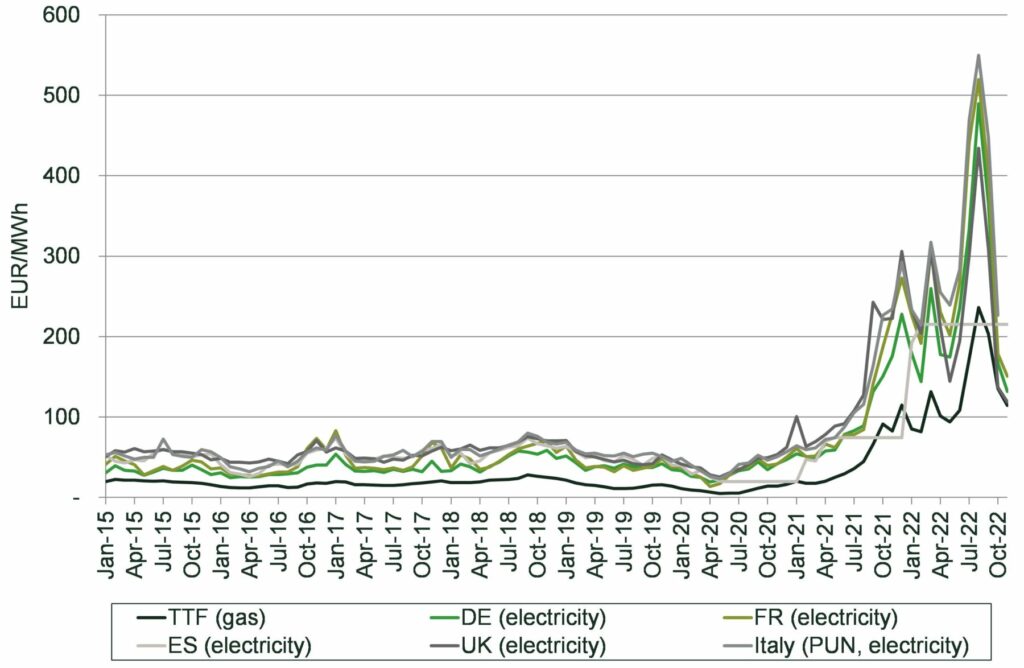

Since 2020, two separate ‘shocks’ have had a significant impact on European energy markets, affecting both demand and supply. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic drove prices down, and once restrictions were lifted electricity and gas demand rebounded. This, plus a combination of other factors, resulted in record high gas and electricity prices,1 as shown in Figure 1. The situation was then exacerbated by the war in Ukraine in 2022.

Figure 1 Wholesale electricity and gas prices

Source: Oxera analysis based on Bloomberg and Gestore dei Mercati Energetici data.

Tensions in the wholesale gas markets quickly translated into higher prices in the electricity markets. The two are closely connected, particularly through the ‘system marginal price’ mechanism.2 On wholesale electricity markets, all accepted bids in a given hour are remunerated at the price offered by the last generator needed to cover demand—known as the ‘marginal’ generator. The generators that are not price-setting (e.g. those that use renewable or nuclear fuel) are called ‘inframarginal’. As gas generators are usually the marginal technology in European markets, gas frequently sets the electricity wholesale price.

High prices on the wholesale markets have resulted in higher retail prices. These escalating prices have raised concerns about the effects on consumers, and started a debate about possible measures to mitigate their impact.

Countries have adopted different measures—there has been limited coordination, especially at the beginning. For this reason the European Commission has issued several guidelines and proposals.3 Several Energy Council meetings have taken place in recent months to agree on common measures.

Overall, measures that have been adopted or are currently under discussion at the national or EU level fall into four broad categories:

- retail market interventions;

- wholesale market interventions;

- security of supply interventions;

- energy consumption reduction.

Retail market interventions

Retail market interventions are among the first measures that governments across Europe introduced to protect consumers from high energy costs. There have been several approaches.

Direct (cash) support. Most European countries have introduced some form of direct support for consumers. For instance, in Germany, consumers received a €300 lump-sum payment as part of their September pay cheque.4 In the UK, the Energy Bills Support scheme will spread £400 of support over energy bills in six instalments.5 Some countries have introduced more targeted support for poorer households, including Portugal (a cash transfer to low-income households and pensioners)6 and Italy (strengthening social bonuses for low-income households).7

Removing various surcharges and levies from retail energy bills. In Italy, general system charges (oneri generali di sistema)8 have been removed from energy bills to ease the burden on consumers.9 Similarly, in Germany the removal of the renewables surcharge on energy bills was brought forward by six months.10 Portugal reduced VAT on electricity and suspended carbon tax increases.11

Retail price cap. Further limits on retail prices have been applied in several countries. For example, the UK already had a retail price cap that was originally designed to protect consumers on pre-payment meters. However, in January 2019 the Default Tariff Cap came into force as a temporary cap on standard variable tariffs and fixed-term default tariffs, and currently remains in place.12 Initially, the cap was updated every six months but—in light of rapidly increasing wholesale prices—this was then reduced to every three months to protect retailers (whose recovery of wholesale costs was limited by the cap).13 In addition, the UK introduced the Energy Price Guarantee, which caps the unit price that consumers pay for electricity and gas until 31 March 2023.14 Germany is planning to introduce a price cap for consumers and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), starting in March 2023, as well as industrial users, starting in January 2023. The policy will aim to maintain demand reduction incentives by capping prices for a minimum viable consumption level only. This is equal to 80% of historical demand for consumers and SMEs, and 70% for industrial users.

While it is understandable that governments have wanted to act quickly to protect consumers, there are at least two factors that policymakers would ordinarily pay attention to when considering such interventions.

First, given the limited resources available for offering financial support, subsidies would usually be targeted, where possible, at those who need them the most, rather than being handed out indiscriminately. That said, some of the initial support schemes that were directed at consumers (e.g. in Germany and the UK) were not means-tested (although the subsidies might be counted as income, and therefore subject to differing tax brackets, which means that people in higher income tax brackets would retain less of the subsidy).

Second, given the lack of alternatives to Russian natural gas in the short term, one key to addressing high energy prices is demand reduction. Policies should therefore ideally ensure that incentives to reduce energy consumption are maintained, while protecting more vulnerable consumers. Simply capping prices for consumers means that they are not exposed to high prices, and therefore do not have as much of a (financial) incentive to reduce their consumption absent the intervention. The German scheme takes this into account, as it exposes consumers to market prices for part of their consumption.

Wholesale market interventions

Several European countries have either proposed, or implemented, interventions in the wholesale gas or electricity markets.

Gas markets. A cap on wholesale gas prices at the EU level has been discussed extensively,15 but so far no measures have been implemented. The latest proposal by the European Commission is a dynamic cap on the TTF—the Dutch gas hub that is Europe’s largest and most liquid market for natural gas.16

Some EU member states have opposed this, as they believe it could make liquefied natural gas (LNG) delivery into the EU less attractive, or reduce incentives to decrease gas consumption. This has made agreement on a price cap difficult, as confirmed by the latest Commission proposal.

Electricity markets. European countries have not proposed capping the market price of electricity directly, but have instead implemented interventions that target a subset of generators, such as gas-fired plants (which are often price-setting), or renewables generators (which are often inframarginal generators).

In June, Spain and Portugal introduced a cap for gas used in electricity generation for one year (with a price of €40/MWh for the first six months, increasing to €70/MWh by the 12th month). Gas-fired generators receive a subsidy to cover the difference between the cap and wholesale gas prices.17 As gas generators are often the marginal generators in the electricity market, and so determine the price paid to other generators, this measure aims to reduce wholesale and, ultimately, retail electricity prices.

In Spain and Portugal, the cap has also resulted in higher consumption and exports to France (which did not introduce a cap), meaning that some of the subsidies benefited French consumers.18 The extension of this measure to the whole of the EU is currently under discussion, but its challenges will need to be addressed (e.g. preventing consumption increases, managing flows with third countries, and ensuring fair financing of the measure).

Some member states and the EU have introduced a revenue cap for inframarginal generators. This leaves price formation on the wholesale market unchanged, but means that inframarginal generators have to pay back any revenue above the cap. Governments use these amounts to fund measures to support consumers. Italy was one of the first countries to introduce a cap, in January 2022, and set it between €56/MWh and €75/MWh, depending on where the generator is located.19 A higher cap of €180/MWh was agreed at the EU level in October 2022.20 The UK has passed a similar price cap into law, although the precise level is yet to be determined by the Business Secretary.21

The decision on whether to cap inframarginal generators’ prices or revenues (and if so, at what level) will reflect a balance between two policy objectives:

- the desire to support consumers. The lower the cap, the lower the prices will be for end-consumers, or the higher the amount of redistribution that governments can provide to customers (as for the current revenue caps);

- the desire to encourage future renewable investments at low cost. A low cap could be interpreted by investors and operators as a sign of regulatory instability, potentially affecting future investment.

Security of supply interventions

In order to mitigate gas security of supply concerns and to reduce dependence on Russian fossil fuels, most of the countries took action in three areas.

Diversification of gas supplies. Various countries tried to maximise the potential of their alternative supplies—via both pipelines and LNG, in line with their geographical position and infrastructure. Efforts included signing new contracts with exporting countries, and procuring new Floating Storage Regasification Units (FSRUs) to increase regasification capacity. For example, Italy signed new contracts for additional gas volumes from Algeria, Egypt and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and mandated Snam (its gas TSO) to procure two FSRUs.22 Germany leased four FSRUs, with two expected to be online by the end of the year. A fifth FSRU terminal has also recently been announced.23

Gas storage filling. Last year, storage levels were below historical averages at the beginning of the season, contributing to gas prices remaining high. For this reason, and to reduce the risk of supply disruptions over the winter, new storage obligations have been introduced at the EU level, with a minimum filling target of 80% for 2022 and 90% for the following years.24 Countries’ efforts resulted in high filling levels (by October, over 92% on average),25 but simultaneously contributed to sustained high prices.

Fuel switching measures. In order to reduce gas consumption, in particular in the power sector, various countries delayed or postponed nuclear or coal phase-out plans, or restarted coal units that had been previously shut down. Germany recently extended the runtime of its three remaining reactors until April 2023, and restarted 12 coal and lignite plants.26 In September, Italy activated the ‘maximisation’ of power production from existing coal units, but high gas prices had already contributed to higher coal output.27

These measures reveal two sets of challenges. First, in order to diversify away from Russian gas and refill their storage facilities, European countries mostly acted in an uncoordinated way, each trying to protect their national interests. This often resulted in countries outbidding each other, increasing competition for (scarce) gas supplies and driving prices up. The setting up of the EU Energy Platform and joint purchasing of gas, as was recently proposed by the European Commission, if implemented, could help to mitigate this challenge and contribute to refilling gas storages ahead of next winter. The latter will be key to ensuring security of supply, but also pose a challenge, especially if Russian flows are completely halted and storage withdrawals this winter are significant.

Moreover, some of the above measures pose a question around their compatibility with decarbonisation objectives in the longer term. New gas contracts and gas infrastructure may result in a risk of a lock-in to gas, slowing down the energy transition. Moreover, there is a risk of stranded or underutilised gas infrastructure should gas demand decrease in line with the latest decarbonisation projections (e.g. the REPowerEU plan). A good balance between the objectives of security of supply and decarbonisation (and affordability) must be found, by looking both at the short and longer term when acting to mitigate current high prices.

Energy consumption reduction

European governments have also undertaken a number of efforts to reduce energy demand, in both the short and long term.

Short-run measures. These are aimed at rapidly reducing ‘non-essential’ gas demand to alleviate pressure on gas prices, and reduce the risk of demand reductions that have harmful social impacts (e.g. on vulnerable consumers or essential industries). European industry has already scaled back operations in response to the sharp price increases.28 Higher prices, however, may achieve less of a reduction in energy usage than could be achieved if other measures, such as legislative requirements, behavioural nudges, or information campaigns were implemented alongside the price reductions.

Most EU countries have undertaken government-sponsored reductions in energy consumption. By contrast, the UK government has previously rejected calls to implement an energy-saving campaign.29 However, the National Grid Electricity System Operator (NGESO) has introduced a policy to incentivise reductions in electricity consumption during peak times.30 According to the latest information, the government is now planning to launch an energy saving campaign.31

In Italy and Spain, laws have been passed that mandate that buildings used by businesses should set temperatures at or below 19°C.32 A similar mandate has been implemented for public buildings in Germany.33 In general, households have more frequently been targeted through awareness campaigns and government recommendations. Unlike those of other member states, France’s ambitious Sobriety Plan is largely voluntary and outlines measures for all consumer types.34

Long-run measures. These mostly refer to subsidising energy efficiency, renewables and low-carbon generation investments. Such measures aim to reduce energy consumption by encouraging the switch to cleaner technologies while accelerating their scalability. Similar measures form an integral part of the REPowerEU plan presented in May 2022,35 where the European Commission proposes to increase the binding target for a reduction in final energy consumption from 9% to 13% by 2030.

While most member states appear to be implementing measures that allow them to meet the previous targets,36 some have started work to meet the new ambitions. For example, the Netherlands has announced a ban on fossil fuel boilers from 2026, and will provide households with financial support to install heat pumps until at least 2030.37 Similarly, France has strengthened its existing subsidy programme for energy-efficiency renovations.38

While efficiency gains are crucial for energy savings, governments should be mindful of potential rebound effects39 and avoid creating suboptimal path-dependencies, such as prioritising particular technologies over others.

The challenges ahead

The latest projections show that in the coming years the European gas balance will continue to be tight, with prices forecast to decrease, but remain above historical averages.40

European governments generally want to mitigate the impact on consumers, while ensuring security of supply and maintaining the EU’s decarbonisation pathway. In order to achieve this, economic theory would suggest that:

- security of supply measures should be closely monitored to ensure that decarbonisation goals remain achievable;

- retail and wholesale interventions should maintain incentives to reduce consumption and invest in clean and flexible technologies;

- security of supply and demand reduction interventions should be closely coordinated, in order to correctly estimate the infrastructural gaps and (new) volumes needed, minimising the risk of stranded assets;

- to the extent that governments want to limit the cost of interventions, they may wish to prioritise targeted support for certain groups.

For member states to meet their objectives and mitigate the effects of the current shocks in the energy markets, it will be key for the EU to act in a coordinated way and progress measures quickly.

1 See Oxera (2022), ‘REPowerEU: managing energy supply and prices in the EU’, 27 May.

2 This is equivalent to a uniform price auction.

3 See Oxera (2022), ‘REPowerEU: managing energy supply and prices in the EU’, 27 May.

4 Bundesministerium der Finanzen (2022), ‘FAQs „Energiepreispauschale (EPP)“’.

5 Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (2022), ‘£400 energy bills discount to support households this winter’, press release, 29 July.

6 República Portuguesa (2022), ‘Governo aprova programa de 2400 milhões para apoiar rendimentos das famílias’, 5 September.

7 These are reductions to electricity and gas bills for vulnerable consumers. See ARERA, ‘Bonus sociali’.

8 These include renewable energy sources support scheme costs, tariff-protection measures for consumers (social bonuses), and nuclear dismantling costs.

9 The measure was initially introduced for Q3 2021, and was later extended until the end of 2022. See Decreto Legge 115/2022.

10 Die Bundesregierung (2022), ‘Stromkunden werden entlastet’, 28 May.

11 República Portuguesa (2022), ‘Governo aprova programa de 2400 milhões para apoiar rendimentos das famílias’, 5 September.

12 Ofgem (2022), ‘Default tariff cap level: 1 October 2022 to 31 December 2022’, 26 August.

13 Ofgem (2022), ‘Price cap – Decision on changes to the wholesale methodology’, 4 August.

14 Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (2022) ‘Energy bills support factsheet’, 1 November. The scheme was initially set to apply for two years, but this was subsequently reduced.

15 See Reuters (2022), ‘EU edges towards gas price cap with more emergency talks’, 25 October.

16 European Commission (2022), ‘Proposal for a Council Regulation on Enhancing solidarity through better coordination of gas purchases, exchanges of gas across borders and reliable price benchmarks’, 18 October. See also European Commission (2022), ‘Proposal for a Council Regulation Establishing a market correction mechanism to protect citizens and the economy against excessively high prices’, 22 November.

17 European Commission (2022), ‘State aid: Commission approves Spanish and Portuguese measure to lower electricity prices amid energy crisis’, 22 June.

18 Centre for Economic Policy Research (2022), ‘The Iberian electricity market intervention does not work for Europe’, VoxEU, 29 August.

19 The government set a cap for each of the seven bidding zones. Decreto Legge. 4/2022, article 15-bis, 29 March.

20 European Commission (2022), Council Regulation 2022/1854, Official Journal of the European Union, 6 October.

21 Addleshaw Goddard LLP (2022), ‘UK Energy Prices Act 2022 – five things you need to know’, 22 October.

22 Castriota, S. and Gambini, R. (2022), ‘L’opportunità per l’Italia di diventare hub del gas europeo’, Lavoce, 8 September.

23 Reuters (2022), ‘Factbox: Germany’s LNG import project plans’, 25 November.

24 Council of the European Union (2022), ‘Council adopts regulation on gas storage’, 27 June.

25 Council of the European Union (2022), ‘Infographic – How much gas have the EU countries stored?’, last accessed 15 November 2022.

26 Clean Energy Wire (2022), ‘German chancellor decides runtime extension for all remaining nuclear plants, ending coalition row’, 19 October. Handelsblatt (2022), ‘Welche Kohlekraftwerke im Oktober wieder in Betrieb gehen’, 6 October.

27 Picchio, G. (2022), ‘Carbone, la “massimizzazione” l’hanno già fatta i prezzi’, RiEnergia, 11 October.

28 For example, European industrial production was 2.3% lower in July 2022 than in July 2021. Financial Times (2022), ‘Will the energy crisis crush European Industry?’, 19 October. Eurostat (2022), Euroindicators, 14 September.

29 McKie, R. (2022), ‘Experts attack government inaction over energy saving guidance’, The Guardian, 9 October.

30 Race, M. and Simpson, E. (2022), ‘Money-off energy scheme launches to avoid blackouts’, BBC News, 4 November.

31 Financial Times (2022), ‘Downing Street draws up UK energy saving campaign’, 24 November.

32 La Moncloa (2022), ‘The government of Spain approves a plan for energy saving and air conditioning management’, 1 August. Gazzetta Ufficiale (2022), ‘LEGGE 27 aprile 2022, n. 34’.

33 Bundesregierung (2022), ‘Ordinance on the security of energy supply on measures effective in the short term’.

34 Government of France (2022), ‘Plan de sobriété énergétique’, 6 October.

35 European Commission (2022), ‘REPowerEU: A plan to rapidly reduce dependence on Russian fossil fuels and fast forward the green transition*’, press release, 18 May.

36 Euractiv (2022), ‘Germany moves ahead with energy efficiency law, amid ongoing EU talks’, 19 October.

37 Euractiv (2022), ‘Netherlands to ban fossil heating from 2026, make heat pumps mandatory’, 19 May. The Beacon (2022), ‘The Netherlands’ big bet on heat pumps’, 19 May.

38 Ministère de l’Économie, des Finances et de la Souveraineté industrielle et numérique (2022), ‘MaPrimeRénov’ : la prime pour la rénovation énergétique’, 13 April.

39 This refers to the undesirable phenomenon that energy savings from efficiency improvements do not materialise as expected due to income effects. This can result from changes in user behaviour—for example, if an increase in efficiency lowers the cost of purchasing/using a product or service, users may react by increasing demand (direct effect). In addition, there are indirect rebound effects, e.g. when the money saved is spent on something else, which in turn consumes energy.

40 See S&P Global Ratings (2022), ‘Europe’s LNG Focus Can Bring Pain As Well As Gain For Utilities’.

Contact

Rebecca Vitelli

Senior ConsultantContributors

Related

Related

Blending incremental costing in activity-based costing systems

Allocating cost fairly across different parts of a business is a common requirement for regulatory purposes or to comply with competition law on price-setting. One popular approach to cost allocation, used in many sectors, is activity-based costing (ABC), a method that identifies the causes of cost and allocates accordingly. However,… Read More

The European growth problem and what to do about it

European growth is insufficient to improve lives in the ways that citizens would like. We use the UK as a case study to assess the scale of the growth problem, underlying causes, official responses and what else might be done to improve the situation. We suggest that capital market… Read More