Striking a balance: legal and economic scrutiny of exclusive dealing in EU sports

Can a dominant sports organiser demand exclusivity from athletes or clubs? The ongoing European Super League and International Skating Union cases on exclusive dealing in sports, currently in front of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), are raising new legal and economics questions. For example, what should be the legal framework for assessing such cases? And what role does economic analysis play in assessing the legality of exclusive dealing in sports?

This article is based on Klein, T. (2023), ‘Exclusive dealing in sports after ESL and ISU’, working paper, SSRN 4351680.

A clash between football’s proposed European Super League (ESL) and governing bodies FIFA and UEFA, along with controversy surrounding the International Skating Union (ISU), has led to a thorough legal examination of exclusive dealing practices in European sports (see the box below). Both cases relate to the ability of sports organisers to demand exclusivity from participating athletes or clubs. Key questions in such cases include the following.1

- Legitimate objectives: what sporting or non-sporting justifications can legitimise competition restrictions imposed by sports organisers?

- Anticompetitive assessment: can exclusive dealing in sports be considered inherently anticompetitive ‘by object’, or should their ‘effect’ on competition be evaluated instead?

- Conflict of interest: what is the relevance of the dual role of sports regulators such as UEFA, FIFA and the ISU as both monopoly regulators and commercial event organisers?

What are ESL and ISU about?

European Super League (ESL) concerns how, in 2021, FIFA and UEFA prohibited top clubs from setting up their own breakaway league in competition with UEFA’s Champions League. In response, the ESL is suing FIFA and UEFA in front of the Madrid Commercial Court No. 17, on the grounds of anticompetitive foreclosure of a potential rival. In the context of these proceedings, the Madrid Commercial Court asked the CJEU for a preliminary ruling.1

In International Skating Union (ISU), the European Commission concluded, in 2017, that the ISU’s exclusivity rules imposed on ice speed skaters had the anticompetitive object of withholding a necessary input to competing organisers—namely, the athletes themselves.2 Although this decision was largely upheld by the General Court in 2020, as of the date of this article (June 2023) the ISU is appealing the decision in front of the CJEU.3

Note: 1 Request for a preliminary ruling from the Juzgado de lo Mercantil n.° 17 de Madrid (Spain) lodged on 27 May 2021 — European Super League Company, S.L. v Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) and Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), Case C-333/21. 2 International Skating Union v. European Commission, Case T-93/18. 3 See, for example, Reuters (2020), ‘Skating body ISU loses appeal against landmark EU penalty ruling’ (last accessed 26 June 2023); and Reuters (2020), ‘Skating-Governing body ISU asks EU top court to scrap penalty ruling’ (last accessed 26 June 2023).

Source: Oxera.

The final judgments by the CJEU are still pending as of June 2023. However, in two non-binding opinions published on 15 December 2022, Advocate General (AG) Rantos provides a glimpse of the potential direction that the CJEU may take in its final rulings.2

In this article, we explore the complexities of these recent cases, shedding light on their implications for EU competition law based on the direction of travel provided by AG Rantos. We also examine the role that economic analysis may play in determining the legality of exclusive dealing practices in EU sports.

The emerging legal framework

When a dominant sports organiser such as UEFA, FIFA or the ISU prohibits participants from participating in rival events, it risks harming competition by excluding rivals from the market and reducing competitive pressure. However, not all restrictions to competition are illegal.

According to the ‘ancillary restraints’ doctrine, competition restrictions are permitted if they are inherent in pursuing legitimate objectives and proportionate to those objectives.3 In ISU, the European Commission argues that the threat of a lifetime ban for non-exclusivity is disproportionate to any legitimate objective—an argument that is not refuted by the General Court or by AG Rantos. In ESL, however, AG Rantos contends that the restrictions imposed by UEFA and FIFA on clubs are inherent and proportionate to legitimate ‘sporting’ objectives, including open European competitions, financial solidarity from elite levels to lower levels of the sport, and competitive balance.

AG Rantos contends that these objectives are legitimate, given the ‘constitutional’ recognition of the ‘European Sports Model’ outlined in Article 165 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (TFEU) and the series of initiatives that led to its adoption (see the box below).4 Moreover, he considers that the economic objective of preventing opportunistic freeriding is legitimate under the ancillary restraints doctrine.

European versus North American sports models

The Council of the European Union defines the European Sports Model as:1

[…] an organisation of sport in an autonomous, democratic and territorial basis with a pyramidal structure, encompassing all levels of sport from grassroots to professional sport, comprising both club and national team competitions and including mechanisms to ensure financial solidarity, fairness and openness in competitions, such as the principle of promotion and relegation.

These characteristics of a pyramid structure, mechanisms of ‘vertical’ financial solidarity from professional- to amateur-level competitions, and open competitions based on sporting merit contrast with what is observed in many North American sports leagues.

For example, the National Basketball Association (NBA), National Football League (NFL), Major League Baseball (MLB) and National Hockey League (NHL) in the USA operate as closed franchises with a fixed number of teams, and without mechanisms of vertical financial solidarity from professional to amateur levels.

However, the North American Sports Model does have more ‘horizontal’ financial redistribution mechanisms in place to promote parity and competitive balance among participants.

1 Council of the European Union (2021), ‘Resolution of the Council and of the representatives of the Governments of the Member States meeting within the Council on the key features of a European Sport Model’, 14430/21, 30 November, para. 8. For more on the European Sports Model see, for example, Sloane, P.J. (2006), ‘The European Model of Sport’, in W. Andreff and S. Szymanski (eds), Handbook on the Economics of Sports, Edward Elgar Publishing; as well as European Commission (2007), ‘White Paper on Sport’, COM(2007) 391 final, 11 July.

Source: Oxera.

If the ancillary restraints doctrine does not preclude Article 101 TFEU (which prohibits anticompetitive agreements), regulations that lead to the exclusivity of participations would violate competition law if they have either the ‘object’ or the ‘effect’ of restricting competition.5 In ISU, the Commission determined that the pre-authorisation and eligibility rules had the anticompetitive object of restricting competition. AG Rantos, however, argues that exclusive dealing does not restrict competition ‘by its very nature’, and that neither the ISU’s broad discretion in authorising other organisers nor the disproportionality of its sanctions establishes anticompetitive object. As the General Court did not examine the effects analysis performed by the Commission, AG Rantos suggests sending the case back to the General Court.

On a potential infringement of Article 102 TFEU (which prohibits the abuse of a dominant position), AG Rantos opines that case law on ancillary restraints can be applied equivalently. If, however, the ancillary restraints doctrine does not preclude Article 102 TFEU, a sports federation acting as both regulator and organiser would not automatically constitute an abuse of dominance. The main obligation of a dominant sports organiser is to ensure that third parties are not ‘unduly’ denied access to the market to the point that competition is distorted, which can be achieved through means other than structural separation. Moreover, structural separation would put the pyramid structure under the European Sports Model at risk.

What role should economics play in this emerging legal framework? In hisOpinions, AG Rantos identifies legitimate sporting objectives based on political grounds. However, economics still plays a significant role in exclusive dealing cases in sports—by contributing to market definition, the theory and quantification of harm, and identifying potential procompetitive justifications for the restriction of competition.

Defining a sports market

Market definition plays a crucial role in EU competition policy to determine competitive constraints and assess dominance. In defining the relevant market, the Commission employs the hypothetical monopolist principle, which identifies as the relevant market the smallest market for which a price increase by a hypothetical monopolist would be profitable. The Commission considers both qualitative and quantitative evidence when undertaking its assessment, including factors such as product characteristics, customer and industry views, price correlations, and diversion ratios.6

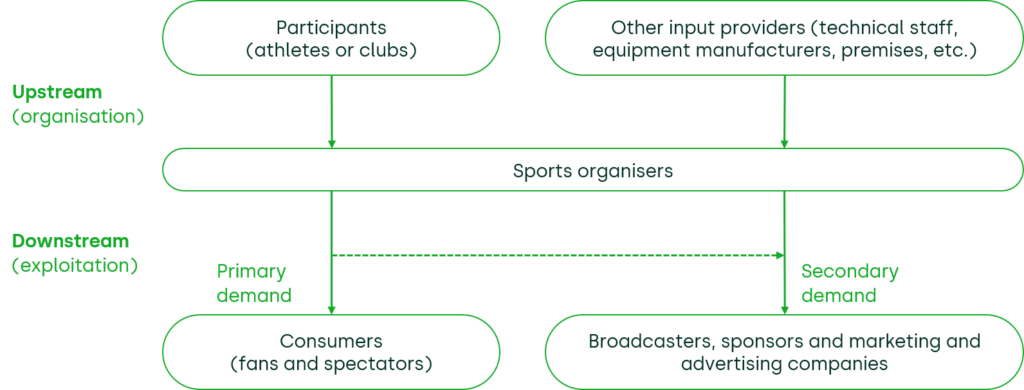

The Commission typically defines the market for sports organisers using a vertical market structure framework that considers downstream commercial exploitation and upstream input acquisition (see Figure 1 below). In this framework, consumers are the primary demand, while broadcasters, sponsors and advertisers are the secondary demand derived from the primary demand by consumers. Participants are then seen as sellers in an upstream market.

Figure 1 Vertical market structure for sports

Source: Klein, T. (2023), based on EU case law and decisional practice discussed therein.

Using this framework, the Commission generally concludes on a single market per sports discipline. However, the extent to which sports organisers face inter-sport competition on the other side of the vertical market remains a case-specific question for which no there is general answer.

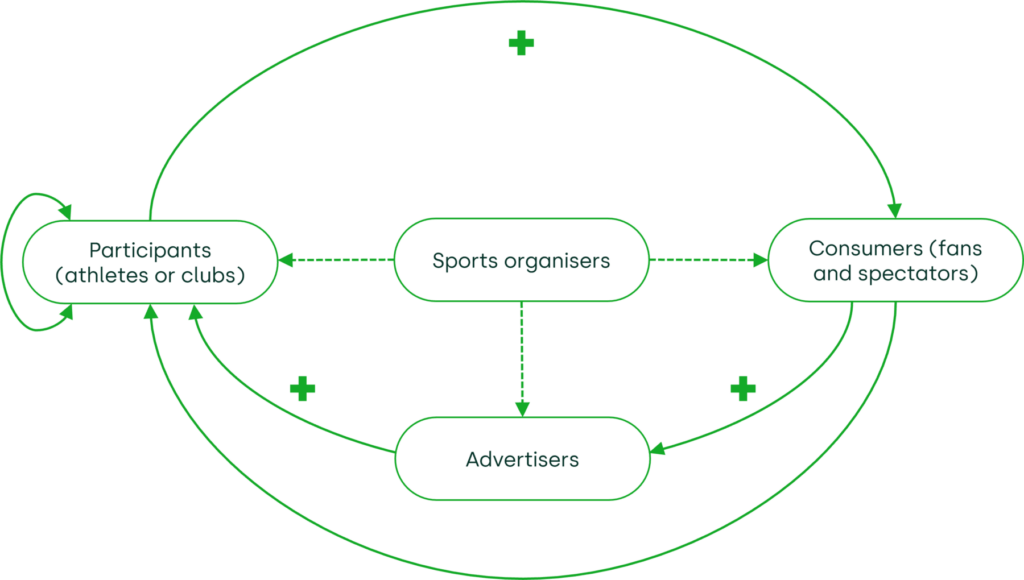

While the vertical market framework structure is helpful, it does ignore potentially relevant indirect network effects across different sides.7 As an alternative, sports organisers can be viewed as multisided platforms that create value for participants, consumers and advertisers by managing their network effects.8 In particular, the more top participants a sports organiser can attract, the more viewers—and, by extension, broadcasters and advertisers—it can attract. In turn, the more consumer and sponsor interest there is in an event, the more attractive it becomes for top participants to participate in it. This creates a positive feedback loop between the different sides that sports organisers aim to manage (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Multisided market structure for sports

Source: Klein, T. (2023).

This multisided market framework challenges the exclusive classification of participants as input providers (as assumed in Figure 1). Instead, it may be better to view them as customers of exposure services.9

Additionally, the presence of strong network effects may affect what is the most economically robust way in which to undertake a market definition exercise. For example, markets with multisided platforms require an explicit choice between a ‘single market’ approach (in which the transaction itself is seen as the product) and a ‘multi market’ approach (in which each side is assessed separately)—a choice that economics can inform.10

Moreover, indirect network effects complicate the assessment of demand substitution at prevailing prices, as platforms may decide to charge zero or even negative prices on one side while monetising on the other. A ‘small but significant, non-transitory increase in price’ (SSNIP) test may then not work well: if the price is zero (or negative), assuming a price increase of (say) five or ten percent does not make much sense.11

How to assess harm?

Exclusive dealing in sports can harm competition and customers by limiting market entry, reducing customer choice and discouraging price reductions, output increases, quality improvements and innovation by incumbent organisers. However, as recognised by AG Rantos, exclusive dealing is not anticompetitive ‘by its very nature’. Moreover, there is a puzzle here: why would participants ever accept an exclusive dealing restriction if this was not somehow to their advantage?12

Different theories identify conditions under which exclusive dealing would be harmful, while still explaining why participants accept them. In particular, participants may face a coordination failure that explains why they accept exclusivity despite its detrimental effects on them. When more participants are required to facilitate entry by a rival organiser, even very small compensation for exclusivity may be sufficient to ‘trap’ participants in a ‘bad equilibrium’, under which everyone continues to accept this exclusivity even though they would be collectively better off without it.

Moreover, a dominant sports organiser may be able to pitch participants against each other through a strategy of ‘divide and conquer’. One way of doing this would be for the organiser to create the prospect of a high compensation to other participants in return for exclusivity at some later stage. In those cases, a participant may be willing to accept exclusivity now in return for a low compensation, as he or she knows that rival entry will be foreclosed anyway. If enough participants sign up to exclusivity now in return for a low compensation, the organiser may not actually need to pay the prospected high compensation.13

Whether or not one can credibly advance an economic theory of harm in any one case requires close scrutiny of (i) the necessary conditions underlying each alternative theory of harm (such as an absence of effective participant coordination and high entry barriers); and (ii) whether these conditions hold in any particular case.

Additionally, or alternatively, one may also wish to undertake an actual quantification of harm. Within the context of sports, various possible quantitative metrics can be considered—including price, output, consumer choice, innovation, geographic expansion and customer satisfaction. On estimating the harm along each of these dimensions, traditional comparator-based methods for estimating competition damages can be employed.14 However, finding suitable comparators in the realm of sports can be challenging, due to inherent differences across sports or a lack of significant temporal variation.

What about the benefits?

Notwithstanding potential harms to competition, exclusive dealing can have procompetitive effects—also in the context of sports. In particular, as recognised by AG Rantos in his ESL Opinion, exclusive dealing can help to prevent opportunistic freeriding behaviour by participants who may switch to another organiser once they or their sport becomes successful.15 The prospect of such behaviour can undermine the incentives for organisers to invest in the development of a growing sport or its participants in the first place—harming both the organiser and its participants. Exclusive dealing restrictions can address this problem by protecting organisers during the recoupment stage of their investment.

Additionally, in the context of sports organisers as a multisided platform, exclusive dealing may help organisers to reduce or reach the minimum viable scale of participants on the one side, and viewers and advertisers on the other. When exclusivity of participants increases viewer interest, banning participant ‘multihoming’ can work to lower and reach the tipping point above which the platform becomes viable.

So, more or less economics?

The ESL and ISU cases have triggered an intense legal scrutiny in the EU of exclusive dealing restrictions by sports organisers. Key in this scrutiny is the concept of ‘legitimate objectives’, the general need to undertake an assessment of anticompetitive effects (as opposed to an anticompetitive object), and the conflict of interest facing sports organisers that are both the monopoly sports regulator and a commercial organiser of sports events.

The CJEU judgments in both cases are still pending. However, based on recent developments, including the opinions by AG Rantos from December 2022, two interesting developments can already be identified.

On the one hand, there appears to be more scope for more economics in assessing actual harm or benefit from exclusive dealing in sports whenever the ancillary restraints doctrine does not apply.

On the other hand, there appears to be more scope for less economics in considering the range of potentially legitimate objectives under the ancillary restraints doctrine. If the CJEU is to follow the opinions by AG Rantos, there will also be a clear endorsement of various sporting objectives as potentially legitimate. However, this does raise the question of whether there may be more non-economic objectives, unrelated to sports, that could similarly be classified as ‘legitimate’—such as sustainability or human rights (which surely enjoy at least as much political legitimisation as the sporting objectives cited).

If so, ESL and ISU may have repercussions even beyond the realm of sports.

1 European Super League Company, S.L. v Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) and Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), Case C-333/21. International Skating Union v. European Commission, Case T-93/18.

2 Opinion of CJEU Advocate General Rantos, Case C-333/21 European Super League Company SL v UEFA and FIFA, delivered on 15 December 2022; Opinion of CJEU Advocate General Rantos, Case C-124/21 P International Skating Union v European Commission, delivered on 15 December 2022.

3 Judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Union in Case C-309/99, J.C.J. Wouters, J.W. Savelbergh, Price Waterhouse Belastingadviseurs BV, delivered on 19 February 2002. For more on the ancillary restraints doctrine, see in particular Whish, R. and Bailey, D. (2011), Competition Law, 7th edition, section 3.4.e.

4 The series of initiatives cited by AG Rantos include the 1995 Bosman judgment by the CJEU (Judgment of the General Court in Case C-415/93 Bosman, delivered on 15 December 1995), the joint declaration on sport annexed to the 1997 Treaty of Amsterdam (Declaration No 29 on Sport, 2 October 1997, 11997D/AFI/DCL/29), the 1999 Commission report on the specific nature of sports in the context of competition law (European Commission (1999), ‘Report from the Commission to the European Council with a view to safeguarding current sports structures and maintaining the social function of sport within the Community framework – The Helsinki Report on Sport’, COM(1999) 644 final, 10 December), the Nice European Council declaration on the specific nature of sport (Nice European Council (2000), ‘Conclusions of the Presidency, Annex IV: Declaration on the specific characteristics of sport and its social function in Europe, of which account should be taken in implementing common policies’, 7–9 December), and the 2007 Commission’s White Paper on Sport (European Commission (2007), ‘White Paper on Sport’, COM(2007) 391 final, 11 July).

5 Article 101(1) TFEU prohibits agreements that are anticompetitive by either their ‘object’ (i.e. anticompetitiveness is inherent in the type of agreement, such as hardcore price-fixing agreements, and for which no actual effect needs to be shown), or their ‘effect (i.e. their actual effects on competition are negative, even if these effects are not inherent to the type of agreement). Concluding on an infringement of Article 101(1) TFEU still leaves open the option of an efficiency defence under Article 101(3) TFEU. For more on the distinction between restriction of competition ‘by object’ and ‘by effect’ see, in particular, Whish, R. (undated), ‘Anticompetitive object or effect’, Global Dictionary of Competition Law, Concurrences, Art. No. 86412.

6 Diversion ratios measure the probability that a consumer that currently buys from one firm would instead buy from another firm if it was incentivised or forced to switch.

7 Network effects are demand-side externalities, where the value to users of a product or service depends on the number of other users. These can be either direct (within the same user group) or indirect (between two user groups), and either positive or negative.

8 For more on market definition in the presence of multisided platforms, as well as concepts such as network effects and platforms, see Oxera (2020), ‘Two-sided market definition: some common misunderstandings’, Agenda, September.

9 The fact that participants often end up paying a negative price to sports organisers—as they may receive prize money and participation compensation that exceed their costs—does not invalidate this classification of participants as customers. As is well known, platforms may end up charging zero, or even a negative price, on one side of the platform in order to optimise the value creation through the management of the different network effects. In that sense, the price charged to each side is nothing more than a value on a continuous number line running from minus infinity to plus infinity.

10 European Commission (2022), ‘[Draft] Commission Notice on the definition of the relevant market for the purposes of Union competition law’, draft revision, 8 November, para. 95.

11 European Commission (2022), ‘[Draft] Commission Notice on the definition of the relevant market for the purposes of Union competition law’, draft revision, 8 November, paras 96–98.

12 This puzzle aligns with the criticism raised by ‘Chicago School’ economists in the 1970s. For example, see Posner, R.A. (1976), Antitrust Law: An Economic Perspective, University of Chicago Press; and Bork, R. (1978), The Antitrust Paradox: A Policy at War with Itself, Basic Books. See also Fumagalli, C., Motta, M. and Calcagno, C. (2018), Exclusionary Practices: The Economics of Monopolisation and Abuse of Dominance, Cambridge University Press, p. 240.

13 Moreover, the Chicago School benchmark assumes that competition between sports organisers would be perfect in the absence of exclusivity. If, instead, competition between organisers would be imperfect, it may actually be the case that the gain to a dominant organiser from exclusivity is enough to compensate the input provider for its loss (which is now lower because of the double marginalisation in case of no exclusivity).

14 This includes comparing across different comparable sports (cross-sectional), across time for the same sport (time-series), or a combination of the two (difference-in-difference). See, in particular, Oxera (2009), ‘Quantifying antitrust damages: towards non-binding guidance for courts’, study prepared for the European Commission, December; and European Commission (2013), ‘Practical guide on quantifying harm in actions for damages based on breaches of Article 101 or 102 of the TFEU’, Commission staff working document, C(2013) 3440, 11 June.

15 Opinion of CJEU Advocate General Rantos, Case C-124/21 P International Skating Union v European Commission, delivered on 15 December 2022, paras 106–108.

Related

Future of rail: how to shape a resilient and responsive Great British Railways

Great Britain’s railway is at a critical juncture, facing unprecedented pressures arising from changing travel patterns, ageing infrastructure, and ongoing financial strain. These challenges, exacerbated by the impacts of the pandemic and the imperative to achieve net zero, underscore the need for comprehensive and forward-looking reform. The UK government has proposed… Read More

Investing in distribution: ED3 and beyond

In the first quarter of this year the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC)1 published its vision for the UK’s electricity distribution network. Below, we review this in the context of Ofgem’s consultation on RIIO-ED32 and its published responses. One of the policy priorities is to ensure… Read More