Switching tracks: the regulatory implications of Great British Railways—part 1

The Labour government’s plan to nationalise private passenger train operators and introduce Great British Railways (GBR) marks a significant shift in the management of the rail network in Great Britain. The stated aim of reform is ‘to deliver a unified system that focuses on reliable, affordable, high-quality, and efficient services; along with ensuring safety and accessibility’.1 While these are laudable aims, questions remain as to how reform will be implemented in practice. In particular, what does this mean for the role of economic regulation?

Over two Agenda articles, we explore the regulatory implications of rail reform. In this first article, we examine the high-level options for regulating GBR, and we start by considering how the proposed industry structure differs from the status quo. In our next article, we will look at specific challenges for rail regulation including how best to incentivise GBR to be efficient and deliver for passengers, and the protections that could be introduced for open access and freight operators.

Note: for those rail experts eager to skip the basics and dive straight into our analysis of the regulatory implications likely to emerge under the new framework, please feel free to skip the following section—after all, we wouldn’t want to bore you with a recap of the current setup!

The current rail industry structure

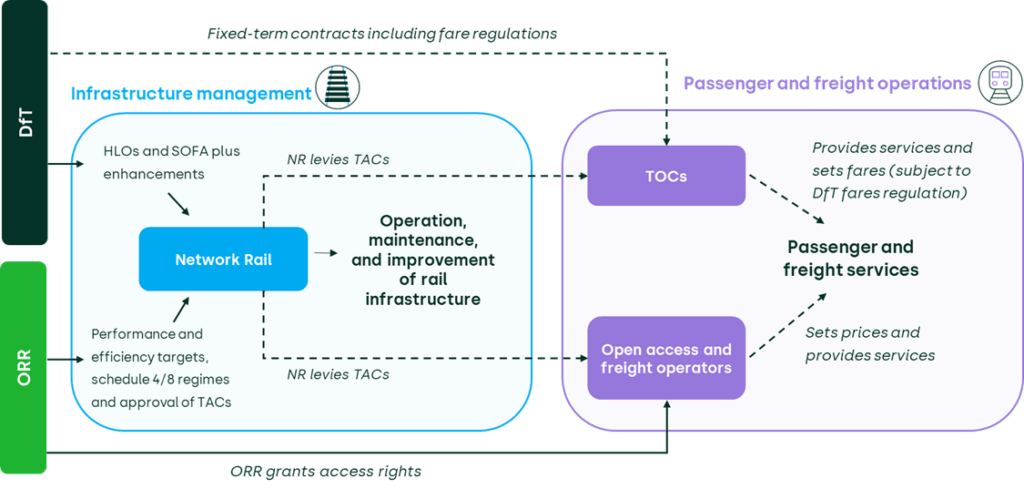

The rail industry in England and Wales is currently characterised by a clear division between infrastructure management and train operations. At the forefront is Network Rail, managing the infrastructure that keeps the railways running smoothly. On the other side, train operating companies are responsible for running the trains and providing passenger and freight services.2

The Department for Transport (DfT) sets the requirements for operators and the outcomes it expects from Network Rail. The Office of Rail and Road (ORR) independently assesses the outputs deliverable by Network Rail for the funding being provided by the government, as well as regulating Track Access Charges (TACs) levied on the operators.

Within this framework, open access, freight, and government-contracted operators all operate services across the heavily utilised network.3 Each player focuses on delivering their business, while a system of incentives—including Schedule 4 and Schedule 8 payments—seeks to ensure that operators minimise undue disruption on one another.4

Figure 1 illustrates the dynamics between these various players.

Figure 1 The current rail structure in England and Wales

Source: Oxera.

The new industry structure

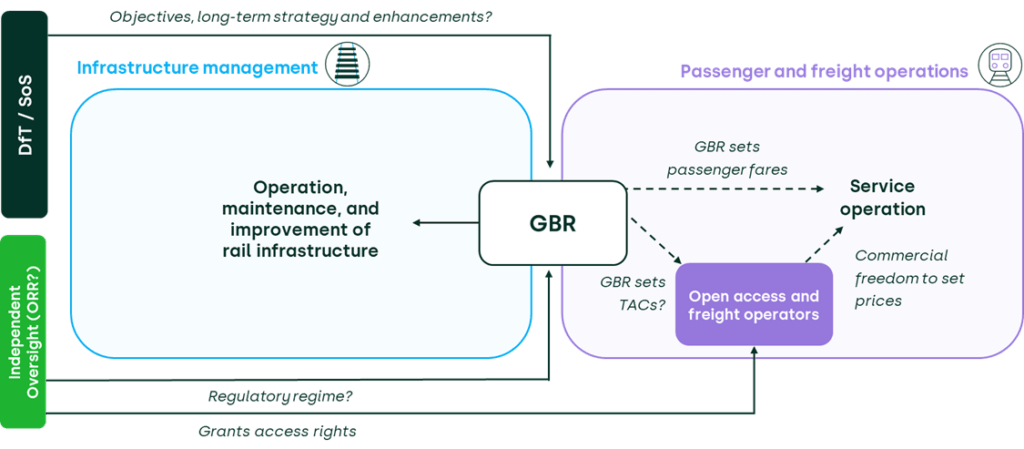

What can we expect under the new industry structure? For now, we know the intention is to:

- nationalise government-contracted passenger rail operations;5

- introduce GBR, a vertically integrated body that will oversee both track and operations for rail services.

Importantly, however, GBR will not fully ‘monopolise’ all rail operations. The government has made it clear that open access operators, freight companies, and devolved operators like Transport for London (TfL) will continue to have room on the network to function independently.6

The DfT is expected to take a more hands-off approach in this setup, setting GBR’s long-term strategy and priorities while only intervening in regard to ‘substantive’ issues.7 Meanwhile, GBR will assume direct control over key aspects such as fare setting, operations, and delivering service improvements. There may also be a role for decentralised, regional decision-making to allocate funding and tailor services to local demand. Additionally, a new watchdog—the Passenger Standards Authority—will be established to independently monitor service quality and push for improvements.8 A key question relates to the role of the ORR as the independent economic regulator, as we outline below.

Figure 2 illustrates what the new industry structure might look like.

Figure 2 The future rail structure

Source: Oxera.

Options for regulating Great British Railways

Under this new structure, it is not yet clear whether the ORR will continue in its current capacity or take on a smaller or expanded role as the independent economic regulator.9

When considering how to regulate GBR, there are several options. We know it is the intention that GBR will be accountable to Parliament, with a continued role for the DfT in setting priorities and a new independent passenger watchdog, the Passenger Standards Authority.10

There is a case to go beyond this with expert independent regulatory oversight of GBR, whether through the ORR or a similar body. Why? Because an independent regulator has the expertise and the resources available to hold GBR accountable for its performance. This includes monitoring cost efficiency and service delivery in line with the responsible use of taxpayer money, and making sure that TACs are fair—including ensuring that open access operators and freight companies have a fair opportunity to use the network and shared facilities such as stations and depots.11

The self-regulation option

Before considering a formal regulatory model, it is worth exploring whether a self-regulation approach, such as the approach previously adopted for the BBC, could be sufficient. This model allows an organisation to maintain internal accountability, provided it has strong governance structures in place, while potentially reducing regulatory burdens.

Designing effective oversight for complex public service organisations like the BBC, NHS, or GBR requires careful thought. Lessons from self-regulation in other sectors can provide valuable insights into achieving the right balance between independence and accountability.

Monitor, and later NHS Improvement, previously oversaw NHS performance at the local level. However, with the Health and Care Act 2022, NHS England has transitioned to a more integrated and devolved approach through Integrated Care Systems (ICSs).12 ICSs are overseen by Integrated Care Boards, which consist of local partners responsible for planning health services, managing NHS budgets, and collaborating with local providers. This model prioritises regional autonomy within a structured framework, striking a balance between independence and alignment with national priorities tailored to local needs.

The history of the oversight of the NHS provides another useful lesson for rail. As with the stated policy intention for rail reform of removing DfT from day-to-day decision making in rail, the Lansley reforms that formed part of the Health and Social Care Act 2012 were intended to remove the Department of Health from day-to-day NHS decision making.13 However, as Jeremy Hunt the subsequent Health Secretary has since stated, this did not work as intended and the Department of Health was drawn back into day-to-day decision making.14 To give GBR true independence it will be important for all parts of Government to have confidence that GBR can manage the railways effectively over time, including when challenges arise.

The BBC provides a different example of self-regulation. In 2017, following recommendations from Sir David Clementi’s independent review of the governance and regulation of the BBC, the government moved away from self-regulation under the BBC Trust model and expanded Ofcom’s role as the BBC’s independent regulator.15 The Clementi Review concluded that ‘the BBC Trust model is flawed. It conflates governance and regulatory functions with the Trust, which leads to confusion about the Trust’s role’.16 As shown in other sectors, independent regulation can therefore provide useful separation of responsibilities.

The experience in other industries demonstrates that self-regulation requires genuine clarity of responsibilities inside the organisation and with government. In addition, regardless of whether self-regulation is the option adopted or not, there is the need for competition authorities to be proactive in meeting the needs of all market participants. Indeed, the Clementi review was clear on this point in relation to the BBC, stating that ‘Nobody argues that the market and competition issues, which increasingly bring the BBC into contact/competition with commercial interests, should be overseen by anyone other than Ofcom’.17

In the context of rail, there are two key challenges that arise from self-regulation that need to be considered. First, is how to ensure that GBR delivers efficiently. It will be necessary, particularly over time, that under self-regulation GBR can provide assurances to government that it is efficient. For example, through some independent scrutiny of a proposed business plan of the outputs that are expected to be delivered for a given level of funding and then subsequent monitoring and reporting of the delivery of those outputs. Second, given a number of operators independent of GBR will continue to run services on the rail network, safeguards are needed for these operators whether they are freight or other passenger operators. We explore these issues and potential solutions in our next article.

The independent regulator option

Although there are alternative governance arrangements, economic regulation can still play an important role for GBR for both i) long-term planning and the associated funding settlements and ii) monitoring, and where necessary and appropriate, enforcement.

On long term planning, an independent regulator with expertise can provide assurance to government and Parliament on the appropriate level of funding and confirm whether this funding can match the government’s requirements. This could form the basis for providing long-term financial certainty to GBR rather than the annual budgets that British Rail was subject to.

Why is this important? Take infrastructure investment, for instance: if GBR knows what public funds will be available over the next few years (via five-year funding settlements), it can make smarter, longer-term decisions. This kind of forward-looking planning is essential for maintaining and improving the rail network.

There is clear precedent for this type of regulatory oversight in other industries, as well as for alternative models that differ from the existing framework originally designed to regulate a private infrastructure manager.18 Take the National Highways model, for example—here, the ORR is tasked with ensuring that the objectives laid out in the Road Investment Strategy (RIS) are met. The RIS is a five-year blueprint for the development and maintenance of England’s motorways and major roads, outlining both funding and priorities for that period. It is a clear, structured approach that helps align long-term goals with the available resources.

In other sectors, like healthcare, we see a similar setup. The NHS in England operates under a Long-Term Plan, which outlines the strategic direction for the next decade.19 NHS England oversees the delivery of this plan, and crucially, the funding is ring-fenced—specifically allocated to areas identified as key priorities. This ensures that money should go where it is most needed, keeping the focus on the Plan’s objectives.

Once a long-term plan is set, an independent regulator can play an important role in monitoring and potentially enforcement. Done well monitoring from the regulator should provide confidence to government that it can step away from day-to-day scrutiny of the regulated organisation. It also helps to make decision-making transparent. For example, we know from the CP7 determination and Network Rail’s CP7 delivery plan, that the company has sought to take a market-led approach, prioritising asset investment on areas of the network which will provide the most value, to support areas of the network that generate higher levels of revenue, while also providing an appropriate level of service to areas where revenue is typically lower.20,21

Importantly, any regulatory framework imposed must be proportionate, avoiding unnecessary complexity and ensuring that the benefits of regulation clearly outweigh the costs. Due to the asymmetry of information between the regulator and the regulated company, it is tempting for the regulator over time to put increasingly more and more checks and balances in place on the regulated entity. However, it is important that this is proportionate and does not limit the autonomy of GBR to act in a joined up and timely manner. Regulators generally all have duties to minimise regulatory burdens. For example, under the Regulatory Enforcement and Sanctions Act 2008, the ORR is required to keep its functions under review and ensure that in exercising those functions it does not impose or maintain unnecessary burdens.22 It will be important that any regulator of GBR also has a similar duty, which they will need to take seriously by properly weighing up whether the benefits of the regulation it imposes outweigh the costs and whether there are alternative approaches that may be more optimal.

There is no obvious ‘right or wrong’ answer here. Each model has its pros and cons. What matters is choosing a framework which facilitates the objectives of reform (i.e. achieving a more joined-up railway), while ensuring that there is effective independent scrutiny of GBR that minimises regulatory burdens.

In our next article, we examine three specific regulatory challenges that arise from rail reform in the areas of efficiency and risk, competition, and how GBR retains a focus on passengers.

Read ‘Switching tracks: the regulatory implications of Great British Railways—part 2’ here.

1 Department for Transport and The Rt Hon Louise Haigh MP (2024), ‘Establishing a Shadow Great British Railways’, 3 September.

2 There are exceptions to this model. For example, in Wales, the Core Valley Lines network was transferred from Network Rail to Transport for Wales on 28 March 2020. Transport for Wales leases its assets to Amey Infrastructure Wales Limited, which acts as the Infrastructure Manager. See Transport for Wales (2024), ‘South Wales Metro: Core Valley Lines infrastructure manager’, accessed 2 December 2024.

3 It should be noted, however, that a number of operators previously contracted by the government have already in effect been nationalised, and are currently under the management of the government’s operator of last resort DfT OLR Holdings Ltd.

4 Schedule 4 and Schedule 8 payments refer to the compensation that train operators receive for the financial impact of planned and unplanned rail service disruption attributable to Network Rail or other train operators. Specifically, Schedule 4 compensates train operators for the impact of planned service disruption, while Schedule 8 compensates train operators for the impact of unplanned service disruption. See Office of Rail and Road (2012), ‘Schedules 4 and 8 possessions and performance regimes’, 26 November, accessed 16 October 2024.

5 On 28 November 2024, the Passenger Railway Services (Public Ownership) Act 2024 received Royal Assent. The Act makes provision for passenger railway services to be provided by public sector companies instead of by means of private sector franchises.

6 Department for Transport and The Rt Hon Louise Haigh MP (2024), ‘Establishing a Shadow Great British Railways’, 3 September.

7 Labour Party (2024), ‘Getting Britain Moving: Labour’s Plan to Fix Britain’s Railways’, p. 17.

8 Department for Transport and The Rt Hon Louise Haigh MP (2024), ‘Establishing a Shadow Great British Railways’, 3 September.

9 Regardless of its future role as independent economic regulator, the ORR is expected to retain other responsibilities, such as safety regulation and approving open access applications. See Labour Party (2024), ‘Getting Britain Moving: Labour’s Plan to Fix Britain’s Railways’, pp. 20, 23.

10 Labour Party (2024), ‘Getting Britain Moving: Labour’s Plan to Fix Britain’s Railways’, p. 16.

11 The government has already indicated that it expects the ORR to retain a role in approving track access applications from open access operators. See Labour Party (2024), ‘Getting Britain Moving: Labour’s Plan to Fix Britain’s Railways’, p. 21.

12 NHS England (2024), ‘What are integrated care systems?‘, accessed 18 November 2024

13 Department of Health (2012), ‘The overarching role (NHS) of the Secretary of State – The Health and Social Care Act 2012’, 30 April.

14 The Health Foundation (2020), ‘Glaziers & window breakers: former health secretaries in their own words’, October, pp. 190–197.

15 Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (2016), ‘Plans to overhaul governance and secure the future of BBC‘, accessed 18 November 2024.

16 Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (2016), ‘A Review of the Governance and Regulation of the BBC‘, accessed 18 November 2024.

17 Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (2016), ‘A Review of the Governance and Regulation of the BBC‘, accessed 18 November 2024.

18 Railtrack was set up as part of British Rail’s privatisation to manage the rail infrastructure. Following a series of issues and accidents, Network Rail took over from Railtrack in 2002, bringing infrastructure management back into public ownership. See House of Commons Library (2010), ‘Railways: Railtrack, 1994-2002’, 24 March, accessed 16 October 2024.

19 NHS England (2024), ‘The NHS Long Term Plan’, accessed 17 October 2024.

20 ORR (2023), ‘PR23 draft determination: supporting document – sustainable and efficient

costs: Part I’, 15 June, p. 25.

21 Network Rail (2023). ‘Our Delivery Plan for Control Period 7: A high level summary’. Accessed 3 December 2024.

22 ORR (2024). ‘The law and our duties’, accessed 3 December 2024.

Contact

Robert Catherall

PrincipalContributors

Related

Related

Decoding the Digital Networks Act: the future of the EU electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework

On 21 January 2026 the European Commission published the long-awaited draft of its Digital Networks Act (DNA)—the proposed new regulation that seeks to ‘modernise, simplify and harmonise EU rules on connectivity networks’.1 As the draft is now being reviewed by the European Parliament and the Council, representing the… Read More

Oxera AI Policy Map – January 2026

For this third edition of the AI Policy Map,1 we have updated our database that tracks key national and supranational AI policy developments across the European Economic Area (EEA) and the UK. This curated collection brings together legal texts, strategy documents and other influential publications relevant to the… Read More