The case of Apple, and the state aid spotlight on multinationals’ tax affairs

On 30 August 2016, the European Commission handed down its largest-ever adverse state aid decision against the tax rulings of a single multinational, requiring Apple to repay €13bn of aid plus interest. The decision follows state aid investigations of the corporate tax affairs of a number of other well-known companies, and will have far-reaching implications for multinationals that currently have, or plan to have, operations in the EU.

The Commission issued its negative state aid decision against Apple after an in-depth investigation into the company’s tax arrangements in Ireland.1 The announcement follows recent decisions by the Commission that Starbucks and Fiat Finance and Trade must repay €20m and €30m in the Netherlands and Luxembourg respectively, as their tax arrangements were found to constitute illegal state aid; and that Belgium must recover €700m from 35 multinationals that were part of the ‘excess-profit’ tax scheme.2 All three decisions are currently under appeal. At the same time, state aid investigations into Amazon and McDonald’s are continuing, with a further 1,000 tax rulings currently being reviewed by the Commission.3

This article explores the main aspects of these investigations, and explains how economic and financial analysis can help multinationals achieve greater certainty about whether their tax arrangements are in line with EU state aid rules, given the Commission’s greater scrutiny in recent years.4

What is the focus of the state aid investigations?

The Commission launched investigations in 2013 into whether certain transfer pricing rulings embedded in Advanced Pricing Arrangements (APAs) agreed by EU member states with companies such as Apple (in Ireland), Amazon and Fiat Finance and Trade (in Luxembourg), and Starbucks (in the Netherlands) breach state aid rules. Transfer pricing is a tool used by multinationals to allocate profits across jurisdictions according to accounting standards and guidelines. The case of Apple is described in the box below.

The state aid investigation of Apple

The investigation of Apple focused on a tax ruling granted by Ireland in 1991, replaced by a similar ruling in 2007, which determined the taxable profits of two subsidiaries of Apple in Ireland—Apple Sales International (ASI) and Apple Operations Europe (AOE).

According to the Commission, the tax rulings endorsed an artificial allocation of profits that had no economic justification, with the majority of ASI’s and AOE’s profits allocated to ‘head offices’ in Ireland. The Commission stated that these head offices existed only on paper, and were not subject to tax in any country. As a result, the majority of ASI’s and AOE’s profits remained untaxed.

According to the decision, ASI accounts for almost all of the unpaid taxes. ASI owns the rights to use Apple’s intellectual property to manufacture and sell Apple’s products in the EU, Africa, the Middle East and India. In return for the rights to the intellectual property, ASI makes payments to Apple in the USA.

The Commission has directed Ireland to recover unpaid tax from Apple over the period 2003–14, which amounts to €13bn before interest.

A novel aspect of the decision is that the aid to be repaid to Ireland can be reduced if other countries require ASI or AOE to pay more tax, and/or if ASI and AOE are required by the US authorities to make additional payments to their US parent to fund research and development.

Source: European Commission (2014), ‘State aid SA.38373 (2014/C) (ex 2014/NN) (ex 2014/CP)—Ireland, Alleged aid to Apple’, 11 June.

Although transfer pricing arrangements in APAs have been the focus of the state aid investigations over the last few years, the scope of the state aid remit has recently expanded. The investigations now cover rulings on double-taxation treaties, with a McDonald’s investigation focusing on whether the company paid appropriate tax in the USA (see the box below), as well as tax settlements, with reported investigations of companies such as Google and IKEA.5

The state aid investigation of McDonald’s

The Commission is currently investigating two 2009 tax rulings from Luxembourg, which, according to the Commission, meant that McDonald’s paid no corporate tax on the profits of McDonald’s Europe Franchising.

In the first tax ruling, Luxembourg confirmed that McDonald’s Europe Franchising was not liable for tax on royalties in Luxembourg, as its profits were subject to tax in the USA. However, it subsequently emerged that this was not actually the case.

McDonald’s then requested a revision to the ruling, claiming that the US–Luxembourg tax treaty allowed for exemptions on income that ‘may’ be taxed in the USA. A second tax ruling was issued by Luxembourg later in 2009, which confirmed that the income of McDonald’s Europe Franchising was not subject to tax in Luxembourg, even though it was not taxed in the USA either.

Source: European Commission (2016), ‘State aid SA.38945 (2015/C) (ex 2015/NN) — Alleged aid to McDonald’s’, Official Journal of the European Union, 15 July.

For measures to be classed as state aid, the following four criteria must all be met:

- there is an intervention by the state or through state resources;

- the intervention distorts, or threatens to distort, competition and trade between member states;

- the intervention is selective by favouring certain undertakings or certain goods;

- the intervention confers an economic advantage on the undertaking.

In the state aid investigations of tax rulings, there is involvement by the state as the rulings are issued by tax administrations. In relation to the first criterion, as the tax rulings are issued by tax administrations, the rulings are imputable to the state. In relation to the second criterion, in state aid cases generally, the level of evidence required to demonstrate that an intervention has the potential to distort competition and trade is relatively low. Therefore, the fact that the subsidiary under investigation is part of a multinational that is active in a number of member states is typically sufficient to demonstrate that a tax ruling has the potential to distort competition.6 More controversial, however, are the questions of whether tax rulings are selective and whether they confer an economic advantage.

The contentious questions: the assessment of selectivity and economic advantage

In state aid cases generally, although the concepts of selectivity and economic advantage are closely related (see the box below), they are usually assessed separately.7

The concepts of selectivity and economic advantage

- Selectivity is assessed by examining whether the proposed treatment to be granted by a member state to a particular company differs from the treatment of other companies that are in a ‘comparable legal and factual situation’.

- An economic advantage is assessed by analysing whether the entity could have obtained the same advantage under normal market conditions (i.e. in the absence of the state intervention). This is normally assessed by applying the market economy operator principle (MEOP).

Source: European Commission (2016), ‘Commission notice on the notion of state aid as referred to in Article 107(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union’, Official Journal of the European Union, 19 July.

In the tax state aid cases, it is typically presumed that an economic advantage is sufficient to demonstrate selectivity.

How is the selectivity of tax rulings assessed?

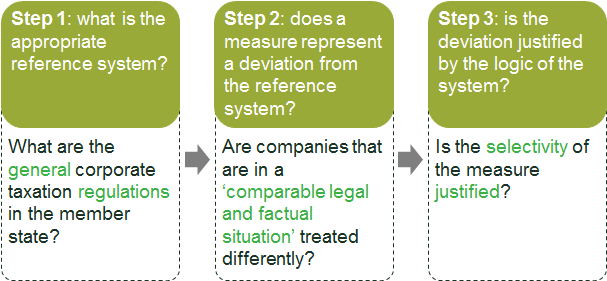

For fiscal measures, in theory a three-step test should be applied to determine whether tax measures are selective (as set out in Figure 1).

Figure 1 Selectivity: the three-step test

In relation to the first step, the Commission typically considers the reference system to be the general corporate income tax system in place in that country.8 In other words, it is presumed that independent companies and multinationals are in the same legal and factual situation.

The second step is to establish whether the APA leads to unequal treatment between multinationals and independent companies. Under the Commission’s approach,9 this assessment generally coincides with whether the measure provides an economic advantage:

in the case of an individual aid measure, as opposed to a scheme, ‘the identification of the economic advantage is, in principle, sufficient to support the presumption that it is selective’.10

If it is shown that the tax measure does lead to such unequal treatment, the third step is used to assess whether this can be justified. In other words, this step is similar to demonstrating whether aid is compatible with EU rules. The compatibility assessment is not considered in detail in the ongoing investigations, however, as the focus is on determining whether the tax measure constitutes aid.

The appropriateness of the approach to assessing the selectivity of the tax rulings is the topic of the appeals by the Netherlands and Luxembourg of the Starbucks and Fiat Finance and Trade decisions.11 As yet, there is no clear guidance on this issue.

For now, presuming that an advantage leads to selectivity effectively reduces the steps of the analysis to an assessment of whether the tax arrangements confer an economic advantage.

What approach is used to assess whether tax rulings confer an economic advantage?

In order to determine whether tax rulings confer an economic advantage, the terms and conditions of intra-group transactions are compared with those between independent companies in comparable transactions.12 According to the Commission:13

a tax measure which results in a group company charging transfer prices that do not reflect those which would be charged…by independent undertakings negotiating under comparable circumstances at arm’s length – confers a selective advantage on that group company

Under the Commission’s approach, a tax ruling that endorses a transfer pricing methodology that does not result in a ‘reliable approximation of a market-based outcome in line with the arm’s-length principle’ confers a selective advantage.14 The OECD has developed guidelines about the application of the arm’s-length pricing principles, an overview of which is set out in the box below.

Overview of the OECD’s arm’s-length pricing principles

The OECD guidelines outline two overall approaches for establishing arm’s-length transfer prices:

- traditional methods that compare the terms of intra-group transactions with those between similar independent companies;

- transactional profit methods that compare the profitability of the subsidiary, or the division of profits between different subsidiaries, with that of similar independent companies.

Source: OECD (2010), ‘Review of Comparability and of Profit Methods: Revision of Chapters I-III of the Transfer Pricing Guidelines’, 22 July.

According to the Commission, not all of the OECD methodologies may approximate a market outcome. Indeed, the Commission has expressed a strong preference for one of the traditional methods—the comparable uncontrolled price (CUP) method, which involves comparing prices of intra-group transactions against prices in transactions between independent companies. For example, in the Fiat Finance and Trade decision, the Commission states that:15

the use of the CUP method should be preferred in cases where comparable transactions can be observed on the market

However, the Commission has started in-depth state aid investigations of tax arrangements that are based on the other OECD methods.16 As a result, the US Treasury has argued that the Commission’s approach is not consistent with the OECD’s guidelines, and others have argued that the approach fails to meet legitimate expectations that compliance with the OECD guidelines should be sufficient.17 This is the subject of the appeals of the Starbucks and Fiat Finance and Trade decisions.18 For example, Fiat Finance is arguing that the Commission’s formulation of the arm’s-length principle introduces significant uncertainty as to when an APA, and indeed any transfer pricing analysis, might breach EU state aid rules.19

How can economic and financial analysis mitigate state aid tax risk?

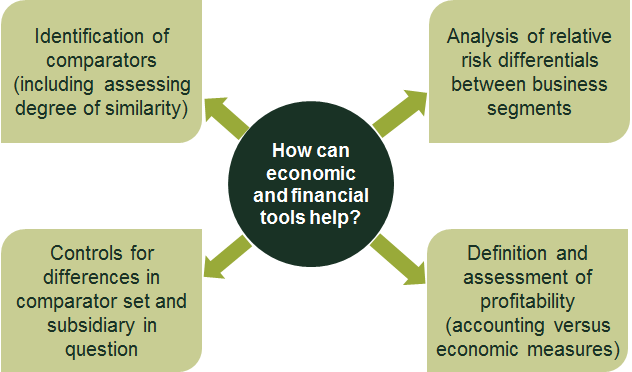

According to the Commission, ‘tax rulings cannot use methodologies, no matter how complex, to establish transfer prices with no economic justification’.20 As demonstrated by the Apple case, it is possible that a state aid investigation can arise several years after a tax ruling is agreed, with significant amounts at stake. In light of the increasing weight placed by the Commission on the economic evidence, together with the widening scope of the investigations, it is therefore now more critical than ever to present evidence in the transfer pricing report, prior to the start of the tax ruling, that the ruling is underpinned by robust economic and financial analysis. Figure 2 shows how economic and financial tools could be used.

Figure 2 How can economic and financial tools help?

The OECD’s arm’s-length pricing methodologies rely on being able to identify similar comparable transactions between independent companies, with adjustments to ensure the accuracy of the comparison.

However, in the case of Fiat Finance and Trade, the Commission raised concerns that the company’s profit in Luxembourg was derived incorrectly, since the comparators used to estimate the rate of return were not sufficiently similar to Fiat Finance and Trade.21 Similar concerns were raised in the Starbucks case. Although adjustments were applied to try to account for differences between the comparators and Starbucks’s subsidiary in the Netherlands, it was concluded that this was conducted incorrectly.22

The Commission’s increasing scrutiny of the economic evidence that underpins the tax rulings highlights the importance of using a systematic approach to derive the set of comparator companies, and controlling for differences between the comparators and the subsidiary in question, using an economically robust approach.

- As with other state aid cases considered under the MEOP and Services of General Economic Interest (SGEI) frameworks, the choice of the comparator set is crucial in the tax state aid cases. In order to improve the robustness of the selection of the comparators, statistical techniques (such as cluster techniques) can be used to quantify the degree of similarity between the set of comparators and the subsidiary in question.

- Once the comparator set has been identified, econometric techniques can be used to control for differences between the characteristics of the subsidiary and those of the set of comparator companies, and the impact on the transfer pricing measure (i.e. prices under the OECD’s traditional methods, or profitability measures under the OECD’s transactional profit methods).23

In a number of cases, including that of Fiat Finance and Trade, the Commission also raised concerns about the application of the OECD’s transactional profit methods. As the Commission places increasing weight on the economic and financial evidence, there is a growing role for economic and financial analysis in improving the robustness of the application of the profitability-based OECD methods. For example, financial analysis can inform the choice and definition of the profitability measure (e.g. whether a margins-based measure or a measure of the return on assets is more appropriate), and in estimating a range for the profitability metric using a robust approach. Indeed, financial benchmarking techniques can be used to derive a robust estimate of the profitability metric, based on data for comparators, while controlling for the differences between the comparator set and the subsidiary in question.

What are the implications of the tax state aid cases?

Commentators have suggested that the way in which the Commission assesses the concepts of selectivity and advantage jointly, and its application of the arm’s-length pricing principles, are not correct in these cases. This is a key point of the appeals of the recent decisions, the outcome of which will not be known for some time. In the meanwhile, it is possible that the investigations could lead to other tax authorities seeking retroactive recoveries from US and EU companies.24

The Apple case highlights the risk that a state aid investigation could start several years after a tax arrangement is agreed. Indeed, the Commission has repeatedly stated its intention to pursue tax rulings based on state aid rules.25 On the day of the Apple decision, the Commission confirmed that a further 1,000 tax rulings from all member states were under review.26 Furthermore, on 1 January 2017, a new Directive comes into effect that aims to encourage greater transparency on tax rulings. It will require an automatic exchange between member states of new cross-border rulings and APAs, with the information exchanged being available to the Commission.27 It is possible that this could trigger further state aid investigations.

Given the increasing weight placed by the Commission on the economic evidence, alongside the factors above and the expansion of the scope of state aid tax investigations to cover double-taxation treaties as well as tax settlements, it is more critical than ever to ensure that tax arrangements are underpinned by robust economic and financial analysis in order to mitigate state aid risk.

1 European Commission (2016), ‘State aid: Ireland gave illegal tax benefits to Apple worth €13 billion’, 30 August.

2 European Commission (2015), ‘Commission Decision of 21.10.2015 on state aid SA.38374 (2014/C ex 2014/NN) implemented by the Netherlands to Starbucks’, 21 October. European Commission (2015), ‘Commission Decision of 21.10.2015 on state aid SA.38375 (2014/C ex 2014/NN) which Luxembourg granted to Fiat’, 21 October. European Commission (2016), ‘Commission Decision of 11.1.2016 on the excess profit exemption state aid scheme SA.37667 (2015/C) (ex 2014/NN) implemented by Belgium’, 11 January.

3 European Commission (2015), ‘State aid SA.38944 (2014/C) (2014/NN) Alleged aid to Amazon’, Official Journal of the European Union, 6 February. European Commission (2015), ‘State aid SA.38945 (2015/C) (ex 2015/NN)—Luxembourg, Alleged aid to McDonald’s’, 3 December.

4 This article represents an update to Oxera’s December 2014 Agenda article, which was written before the outcomes of the investigations into Starbucks, Fiat Finance and Trade and Belgium’s excess profit scheme were known, and prior to the start of the McDonald’s investigation. It also reflects insights from Oxera’s work for a range of clients on tax state aid matters. Oxera (2014), ‘When tax attacks! Corporate tax arrangements under EU state aid scrutiny’, Agenda, December.

5 Brunsden, J. and Noble, J. (2016), ‘European Commission to examine Google’s UK tax deal’, Financial Times, 28 January.

6 However, one of the pleas by Fiat in the appeal of the decision is that the Commission did not show that the APA was liable to distort competition. For further details, see General Court (2015), ‘Action brought on 29 December 2015—Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v Commission’, Case T–759/15.

7 As an example, see European Commission (2016), ‘Commission Decision of 1 October 2014 on the State aid SA.21121 (C29/08) (ex NN 54/07) implemented by Germany concerning the financing of Frankfurt Hahn airport and the financial relations between the airport and Ryanair’, Official Journal of the European Union, 24 May.

8 European Commission (2015), ‘Commission Decision of 21.10.2015 on state aid SA.38374 (2014/C ex 2014/NN) implemented by the Netherlands to Starbucks’, 21 October, para. 232.

9 European Commission (2015), ‘Commission Decision of 21.10.2015 on state aid SA.38374 (2014/C ex 2014/NN) implemented by the Netherlands to Starbucks’, 21 October, para. 253.

10 European Commission (2015), ‘State aid SA.38945 (2015/C) (ex 2015/NN)—Luxembourg, Alleged aid to McDonald’s’, 3 December. The quoted phrase is from Case C-15/14 P Commission v MOL ECLI:EU:C:2015:362, para. 60; and Case T-385/12 Orange v Commission ECLI:EU:T:2015:117.

11 General Court (2015), ‘Action brought on 23 December 2015—Netherlands v Commission, Case T-760/15. General Court (2015), ‘Action brought on 30 December 2015—Luxembourg v Commission’, Case T–755/15.

12 European Commission (2016), ‘Commission Decision of 11.1.2016 on the excess profit exemption state aid scheme, SA. 37667 (2015/C) (ex 2015/NN) implemented by Belgium’, 11 January, para. 149.

13 European Commission (2016), ‘Commission Decision of 11.1.2016 on the excess profit exemption state aid scheme, SA. 37667 (2015/C) (ex 2015/NN) implemented by Belgium’, 11 January, para. 147.

14 European Commission (2016), ‘Commission notice on the notion of state aid as referred to in Article 107(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union’, Official Journal of the European Union, 19 July, para. 171. In the Opening Decisions, the European Commission referred to the MEOP. This terminology has been dropped from the final decisions, although the basis for the test is the same.

15 European Commission (2015), ‘Commission Decision of 21.10.2015 on state aid SA.38375 (2014/C ex 2014/NN) which Luxembourg granted to Fiat’, 21 October, para. 132.

16 European Commission (2014), ‘State aid S.A. 38944 (2014/C)—Luxembourg, Alleged aid to Amazon by way of a tax ruling’, 7 October, para. 45.

17 US Department of the Treasury White Paper (2016), ‘The European Commission’s Recent State Aid Investigations of Transfer Pricing Rulings’, 24 August.

18 General Court (2015), ‘Action brought on 23 December 2015—Netherlands v Commission’, Case T-760/15.

19 General Court (2015), ‘Action brought on 29 December 2015—Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe v Commission’, Case T–759/15.

20 European Commission (2015), ‘Commission decides selective tax advantages for Fiat in Luxembourg and Starbucks in the Netherlands are illegal under EU state aid rules’, press release, 21 October.

21 European Commission (2015), ‘Commission Decision of 21.10.2015 on state aid SA.38375 (2014/C ex 2014/NN) which Luxembourg granted to Fiat’, 21 October.

22 European Commission (2015), ‘Commission Decision of 21.10.2015 on state aid SA.38374 (2014/C ex 2014/NN) implemented by the Netherlands to Starbucks’, 21 October.

23 Econometric techniques can be used to control for the influence of other factors that may affect the level of prices or profitability, such as the degree of competition, the country of the firm’s operations, and leverage and earnings volatility.

24 Jopson, B. and Beesley, A. (2016), ‘US in last-ditch effort to quash Brussels tax demand on Apple, Sharp escalation of transatlantic feud over bill for billions of euros’, Financial Times, 24 August.

25 European Commission (2016), ‘Communication from the Commission, Commission Notice on the notion of State aid as referred to in Article 107(1) TFEU’, para. 170.

26 European Commission (2016), ‘State aid: Ireland gave illegal tax benefits to Apple worth up to €13 billion’, press release, 30 August, accessed 3 September 2016.

27 For further details, see European Council (2015), ‘Cross-border tax rulings: transparency rules adopted’, 8 December, accessed 7 September 2016.

Download

Related

Oxera AI policy map – October 2025

Drawing on Oxera’s combined expertise in digital policy and regulation, as well as in analytics, data science and AI, we have developed a database that tracks key national and supranational AI policy developments across the European Economic Area (EEA) and the UK. This curated collection brings together legal texts, strategy… Read More

Ofgem’s RIIO-ED3 SSMC

On 8 October 2025, Ofgem published its Sector Specific Methodology Consultation (SSMC) for the forthcoming RIIO-ED3 (ED3) price control for GB electricity distribution networks. We look at some of the key themes emerging from the consultation ahead of the final methodology decision, which is expected to be published in December… Read More