The energy crisis: where next for the UK energy retail sector?

What were the root causes and costs of the recent supplier failures in the UK energy retail market? The Board at Ofgem (the energy regulator for Great Britain) asked Oxera to conduct an independent review of Ofgem’s role in the supplier failures, and to draw out lessons learned and recommendations—with a view to shaping better future regulation. We set out some of our key findings and the implications for the sector going forward.

Over the course of 2021–22, wholesale gas and electricity prices have risen to unprecedented levels. This has led to significant increases in customer bills and instigated a spate of supplier failures in the energy retail market in Great Britain. In most cases, failed suppliers’ customers have been passed on to still-active suppliers through the Supplier of Last Resort (SoLR) process. An exception has been made for the largest supplier to have failed, Bulb Energy, which is now run by a court-appointed administrator and funded by the government through the Special Administration Regime (SAR).

The SoLR process allows for the supplier taking on the customers of a failed supplier to recover the incremental costs of doing so from a levy mutualised across future bill payers. This is recovered through the Network Costs building block of the Default Tariff Cap and has been implemented through an increase in the standing charge.

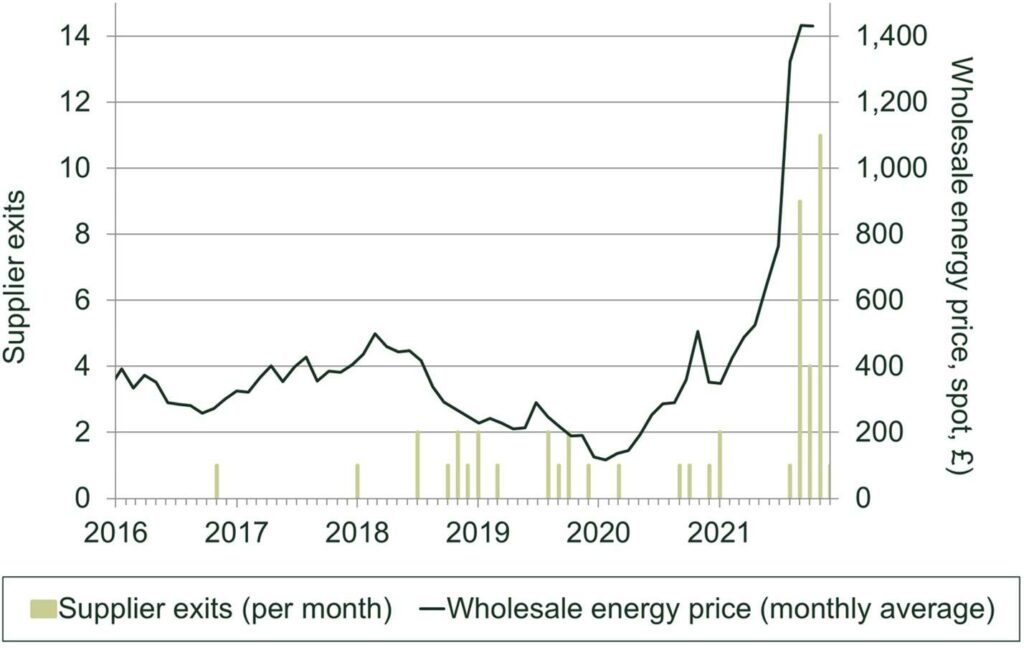

The considerable costs associated with transferring customers to new suppliers—driven primarily by the financial burden the new supplier faces in providing these customers with energy at a price capped below current spot prices (see Figure 1 below)—are being mutualised across current and future bill payers, as described above. The first instalment of £1.8bn1 will be recovered through customer bills over the period April–September 2022, increasing the bill for a typical2 household on a standard variable tariff by the equivalent of £68 p.a.

The costs borne by consumers and/or taxpayers may rise further to account for:

- additional Last Resort Supply Payment claims for the costs associated with suppliers that have already failed;

- the accrued costs of running the SAR for Bulb if these exceed the proceeds of an eventual sale by the government;

- costs associated with additional suppliers exiting the market.

Figure 1 Exits from the retail energy supply market in Great Britain (bars, left axis) against wholesale spot prices (line, right axis)

Source: Wholesale prices from Ofgem, ‘Wholesale market indicators’, accessed 2 February 2022; TDCVs from Ofgem (2020), ‘Decision on revised Typical Domestic Consumption Values for gas and electricity and Economy 7 consumption split’, 6 January; entry dates calculated based on market share data provided by Ofgem.

The causes of supplier failure

The starting point for our review3 was to understand the factors underpinning the incidence of supplier failure in the period 2021–22. We analysed publicly available data (such as that published by Ofgem, and from Companies House) and confidential data disclosed to Ofgem, and conducted a range of interviews with directors and board members of Ofgem (past and present), members of government and industry.

The key finding from our analysis of the empirical data was that most suppliers that would go on to fail had some combination of the following characteristics that were detrimental to their financial resilience:

- negative equity balances in the years leading up to their failure;

- poor liquidity and low levels of working capital;

- over-reliance on customer credit balances to finance their operations;

- either unhedged, or not substantively (i.e. more than 50% over nine months or more) hedged, positions.

Many of the suppliers that remain active in the market had fewer of these characteristics, or exhibited them to a lesser degree. Nonetheless, we identified sector-wide trends of declining profitability, declining equity balances and declining liquidity over the period 2015–21.4

A key area of insight from the interviews was the range of business models followed by suppliers in the market, and the implications that these had for financial resilience. Two specific business models were highlighted as contributing to the rise and fall of suppliers that would exit the market over 2021–22. These were:

- a timing model, in which suppliers entered or sought to grow market share at favourable moments in the wholesale market;

- a growth model, where suppliers used customer prepayments to fund future growth.

Both models had the scope to expose suppliers to supply or demand shocks and contributed to market instability. While it was not possible with the available data to conclusively determine the extent to which these business models were followed by specific suppliers, the empirical evidence supported suppliers following aspects of both models.

These factors limited suppliers’ ability to absorb shocks amid demand uncertainties in the COVID-19 period as well as rapid and sustained increases in wholesale energy prices, which have been especially pronounced since autumn 2021. Suppliers were unable to raise prices to match the speed and scale of input cost rises for customers on fixed contracts, or for customers on standard variable tariffs that were capped by the Default Tariff Cap.

Regulating the energy supply market

Given this market context, we assessed the extent to which the ability of suppliers to enter, remain and grow in the market with low levels of financial resilience and through pursuing risky growth models was enabled by (or in spite of) how the sector was regulated.

Considering the overall package of incentives and restrictions that a supplier faced across its lifecycle, we found that it was possible to enter the market and grow to a considerable scale while committing minimal levels of capital. This was enabled through the use of customer credit balances and costs collected in advance to fund Renewable Obligations as alternatives to working capital. While superficially increasing the degree of competition in the market, this created the opportunity for prospective suppliers to enter the market on the basis of a ‘free bet’. By pursuing a high-risk/high-reward business model, such suppliers could benefit from any upside, while being able to exit at potentially no or minimal cost if the downside materialised.

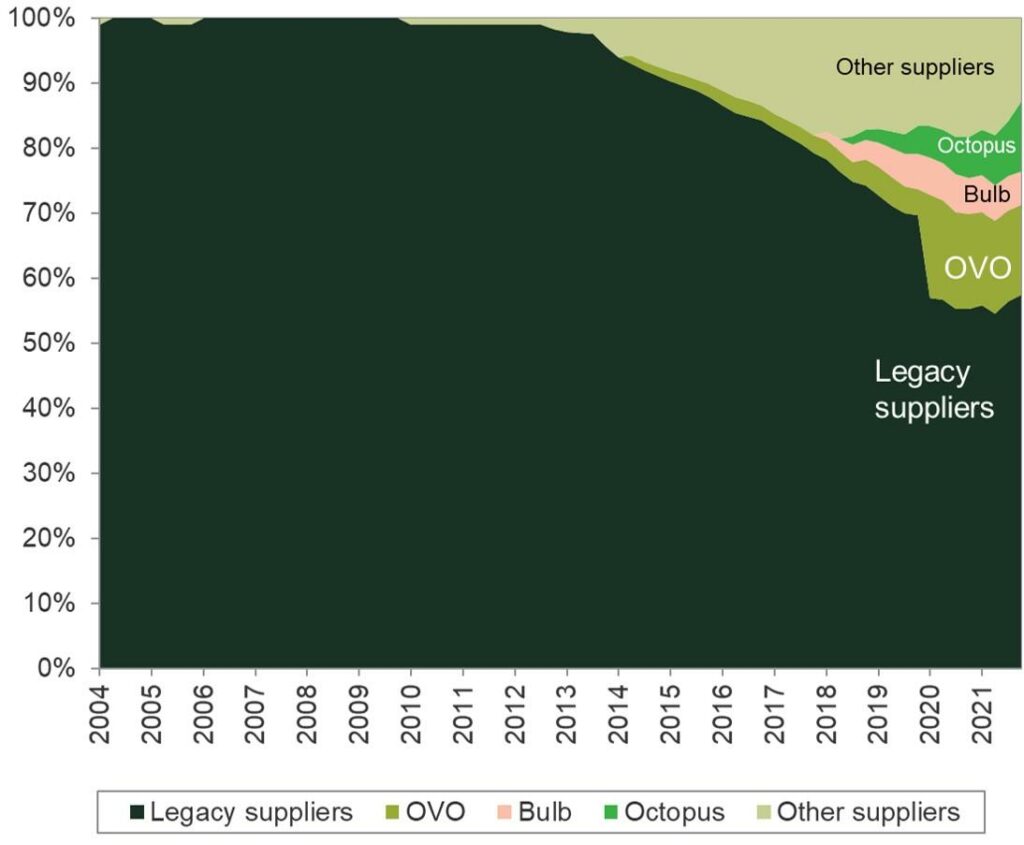

The decision to maintain low barriers to entry and limit ongoing controls on suppliers’ financial resilience was informed by a regulatory philosophy, shared across the wider policy space (such as with the Competition and Markets Authority and the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS)), that saw the promotion of competition as the means to improve outcomes for customers. This was influenced by the history of the supplier market after it was opened up to competition in the 1990s. Up to 2016, the six large legacy suppliers (the ‘Big 6’) had a seemingly permanent grip on over 90% of the market (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Electricity supply market share (domestic), 2004–21

Source: Oxera analysis based on market share data available as part of Ofgem’s publicly available Retail Market Indicators data up to Q3 2021, and non-public data on market shares by supplier for Q4 2021 taken from Ofgem, ‘6.4_Raw domestic market share_MeterPointData for Board_Oxera_2022’.

Thereafter, a number of non-legacy suppliers (including many of those that would go onto fail) were able to rapidly grow their customer books over the period 2016–21. This growth coincided with a period featuring a large gap between the cheapest tariffs available in the market and the typical standard variable tariff charged by a legacy provider, as well as high rates of consumer switching and declining (and, in many cases, persistently negative) levels of profitability. While those customers that did shop around benefited from significantly lower energy prices, some of the suppliers offering such deals were potentially exposed if the wholesale market were to turn against them.

From interviews with stakeholders, we understand that there was never a regulatory intent to pursue a regime of ‘zero supplier failure’—rather, there was an acceptance that non-resilient players would enter and exit, with an expectation that such players would be small and have low numbers of customers. However, the growth of small players over time meant that the failure of such non-legacy suppliers would then go on to impose a higher degree of mutualised costs as a result of the SoLR process.5

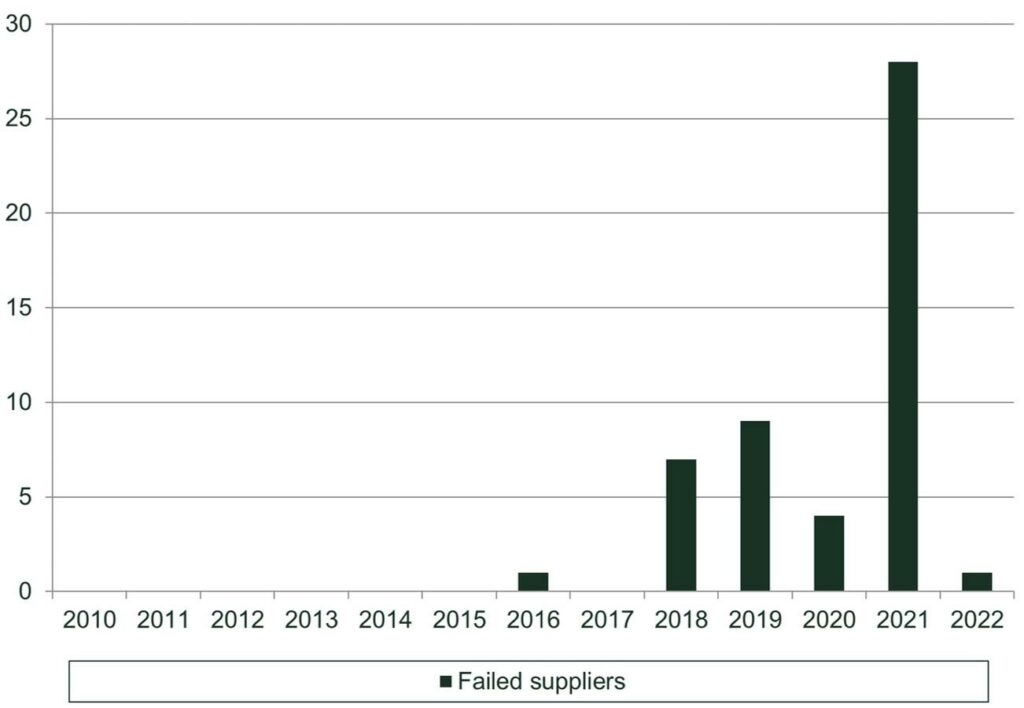

Accordingly, as the market share of some riskier non-legacy suppliers grew, so did the potential consequences of such firms exiting. The growing risk that these customer books represented may have been masked by the low incidence of supplier failures experienced before 2018 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Suppliers exiting the market, 2010–22

The price cap and the costs of supplier failure

As the number and size of non-legacy suppliers grew—with some doing so by adopting risky business models with minimal working capital buffers—in 2018 the government legislated to introduce a price cap for customers on a standard variable tariff. Adopted alongside a largely procompetitive, light-touch approach to regulation, this had the scope to create competitive distortions in the event of rising wholesale energy prices.

Calibrating a price cap that was designed to be ‘a tough cap ensuring loyal consumers pay a fair price that reflects efficient costs’6 may have left suppliers with insufficient headroom to deal with future shocks—which was reflected in some suppliers’ low levels of profitability and low levels of working capital going into 2021. It also increased both the likelihood and costs of supplier failure in an environment of rapidly rising wholesale prices. The periodicity of the price cap exposed suppliers to a narrowing or even negative gap between spot energy prices and a fixed level of remuneration for the wholesale costs incurred for the duration of the price cap—increasing the probability of supplier failure.7

Under current insolvency arrangements, any financial derivatives used by the supplier to hedge the price of wholesale energy are not passed on to the SOLR that takes on a failed supplier’s customer book.

An additional cost that can be claimed by suppliers under the SoLR process is any gap between the spot price of energy on wholesale markets and the amount that can be recovered from customers under the price cap. As a result of recent wholesale price movements, over 90% of the mutualised costs of supplier failure to date result from such claims—or £1.7bn of £1.8bn in SoLR costs.

Figure 4 below shows (in dark green) the allowance within the price cap for wholesale energy costs; and (in light green) the wholesale cost to supply a typical household based on spot prices. The large and growing gap between the price cap allowance (dark green) and spot price (light green) effectively represents the potential cost to be mutualised for a given customer—and this gap grows substantially over 2021–22. The longer the periodicity of the price cap, the greater the scope for such costs.

Figure 4 Wholesale cost to supply a typical household, allowance in the Default Tariff Cap against spot price (£/year)

Source: Oxera analysis based on Ofgem (2022), ‘Annex_2_wholesale_cost_allowance_methodology_v1.9’, January.

In summary, our review drew the following conclusions.

- A number of poorly capitalised suppliers were able to grow to cover a substantial share of the market by pursuing risky models and maintaining low reserves of capital.

- The combination of rising wholesale prices and the price cap left them facing a large financial shock for an indefinite period of time that they were ill-equipped to manage, especially if they had low capital reserves and levels of hedging.

- The catalyst for their failure—a mismatch between the wholesale cost of energy and the price cap as wholesale prices rose—considerably increased the costs to be mutualised.

- Finally, as a degree of exposure to wholesale prices is common to all suppliers, the number of suppliers that failed was heavily correlated with the rise in wholesale prices—leading to numerous failures in quick succession.

Looking ahead

In the short run, Ofgem’s focus will rightly be on the protection of consumers as the pathway of future wholesale energy prices remains uncertain. This will require a careful balance between affordable bills and market stability. From an affordability perspective, Ofgem will need to ensure that any price increases to accommodate further rises in wholesale prices are fair and proportionate. If wholesale prices begin to fall, as many hope, Ofgem will need to monitor how this is reflected in customer bills.

Following the Queen’s Speech of May 2022,8 it looks likely that Ofgem will be able to effect this directly through setting the Default Tariff Cap, until at least 2023. However, in so doing, Ofgem will need to balance the price that consumers pay with the potential costs if more suppliers enter insolvency. For as long as wholesale prices continue to substantially outstrip the allowance in the price cap, the costs of supplier failure will remain significant.

In the longer term, Ofgem will need to consider what lessons it can learn for how it regulates and monitors energy retailers. This might include regulation or monitoring of capital adequacy, arrangements to protect customer credit balances, and assurance around suppliers’ exposure to wholesale cost volatility and other risks. In June 2022, Ofgem published a consultation9 on policy options to improve supplier financial resilience drawing on many of the issues outlined above—in particular, the protection of customer credit balances, funds collected for Renewables Obligations, the transfer of financial derivatives in the event of supplier failure, and capital adequacy.10

1 For claims made by SOLR up to December 2021.

2 Based on typical domestic consumption values.

3 Oxera (2022), ‘Oxera independent review of Ofgem’s regulation of the UK energy supply market’, 6 May, accessed on 30 June 2022.

4 As measured by the current ratio—i.e. the ratio of current assets to current liabilities.

5 We assume that the perceived risk of the failure of a legacy supplier (as opposed to orderly exit or acquisition) was considered to be remote given the backing of large parent companies and access to credit lines.

6 Ofgem (2019), ‘Our strategic narrative for 2019-2023’. 11 July, p. 14.

7 Prior to Ofgem’s announcement in June 2022, the Default Tariff Cap was reset every six months. Ofgem is currently consulting on reducing the periodicity to three months.

8 The Queen’s Speech forms part of the State Opening of Parliament at the beginning of a new session of the UK Parliament. This outlines the government’s agenda for the coming year. See UK government (2022), ‘Queen’s Speech 2022’, 10 May, accessed 30 June 2022.

9 Ofgem (2022), ‘Policy Consultation: Strengthening Financial Resilience’, 20 June, accessed 30 June 2022.

10 Ofgem (2022), ‘Policy Consultation: Strengthening Financial Resilience’, 20 June, accessed 30 June 2022.

Related

Future of rail: how to shape a resilient and responsive Great British Railways

Great Britain’s railway is at a critical juncture, facing unprecedented pressures arising from changing travel patterns, ageing infrastructure, and ongoing financial strain. These challenges, exacerbated by the impacts of the pandemic and the imperative to achieve net zero, underscore the need for comprehensive and forward-looking reform. The UK government has proposed… Read More

Investing in distribution: ED3 and beyond

In the first quarter of this year the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC)1 published its vision for the UK’s electricity distribution network. Below, we review this in the context of Ofgem’s consultation on RIIO-ED32 and its published responses. One of the policy priorities is to ensure… Read More