The expert hot tub: choose your model

Invented in the southern hemisphere, expert hot tubs are increasingly used in competition law cases in Europe. They allow the evidence from economic experts (party-appointed and/or court-appointed) to be heard concurrently in court. These hot tubs come in different shapes and sizes. Dr Gunnar Niels, Managing Partner at Oxera, proposes a categorisation of the various models and discusses their pros and cons.

This article is based on a chapter in the forthcoming book Niels, G., Jenkins, H. and Kavanagh, J. (2023), Economics for Competition Lawyers, third edition, Oxford University Press.

Competition lawyers and economists routinely work alongside each other as complements (not substitutes). Much still needs to be done to extend good practice in the use of economic evidence across jurisdictions. Economists do not always have a favourable reputation, and are the butt of many a joke: the two-handed economist (on the one hand, on the other); the economist who dismisses reality because it doesn’t fit the theory; ask two economists and you get three opinions; and so on.1 That competition law is a complex field is not the fault of economists—to quote the Competition Appeal Tribunal: ‘competition law is not an area of law in which there is much scope for absolute concepts or sharp edges’.2 However, economists can help by shedding light on complex market dynamics and outcomes.

How can courts determine what weight and credibility to attach to the evidence of economic experts, especially in situations where two experts reach different conclusions? Useful principles have been developed in various jurisdictions. Here I discuss the ‘expert hot tub’, an Australian invention that is increasingly being used in court cases across Europe.

The duty of experts to help the court, talk to each other, and agree to disagree

There are various ways to involve experts in court proceedings, and the rules differ across jurisdictions. Parties can each appoint their own expert, or (less commonly) they can appoint one expert jointly. Courts may themselves appoint an expert.

The system of party-appointed experts used in the English courts is widely recognised as effective. It combines a number of powerful mechanisms that provide the right incentives for experts to do their jobs properly: (i) a legal duty on the experts to help the court; (ii) a requirement on the experts to talk to each other and produce a joint statement identifying points of agreement and disagreement; and (iii) (if the case goes to trial) the experts having their ‘day in court’, where they can explain their work and the other party can subject it to robust cross-examination.

Expert discussions usually take place after submission of the expert reports and before the trial, but are also increasingly used during earlier stages of the case, so that the experts can agree on a methodology and assist the legal teams and court with identifying relevant data for disclosure. Together with the duty to the court, the requirement on experts to get together and narrow down (minimise) the scope of issues considered in the dispute can be an effective mechanism to help courts understand the economics of the case. That the mechanism of the expert meeting and joint expert statement can work satisfactorily is also borne out by the following quote from a damages judgment:

The quantum experts have managed to make very good progress in agreeing figures. This meant that the issues between them were more limited. Both [expert 1 and expert 2] were impressive witnesses and although their approaches on particular issues differed, this was the result of opinion on such matters as validation of costs. I have therefore been able to see clearly what their views are and decide which view I prefer on particular issues.3

In addition to the duty to the court and the requirement to meet with opposing experts, economists face the prospect of cross-examination by a barrister representing the other side, possibly complemented by questions from the court itself. This is the most vigorous form of rattling that the expert’s black box can get in court, and provides a further incentive for them to produce a robust analysis. Cross-examination of experts is increasingly common in many jurisdictions and also in arbitrations, although there are still jurisdictions where, somewhat unsatisfactorily, experts do not routinely get their day in court—and this is a missed opportunity for courts to get a better understanding of the economic evidence pertinent to the case.

Expert hot tubs: different shapes and sizes

One method with which the experts can be tested is through concurrent evidence in court, now usually referred to as the expert ‘hot tub’. This method originated in Australia (where it was also called the expert ‘conclave’), and is now increasingly common elsewhere.

Like real hot tubs, expert hot tubs come in different shapes and sizes, but in essence they are a blend of the expert discussions and cross-examination discussed above. The experts appear together in court to exchange views and answer questions from the barristers and the court. As explained by an Australian judge (Rares, 2013):

In many situations calling for evidence, the ‘hot tub’ offers the potential for a much more satisfactory experience of expert evidence for all those involved. It enables each expert to concentrate on the real issues between them. The judge or listener can hear all the experts discussing the same issue at the same time to explain each of their points in a discussion with a professional colleague. The technique reduces the chances of the experts, lawyers, and judge, jury, or tribunal misunderstanding what the experts are saying.4

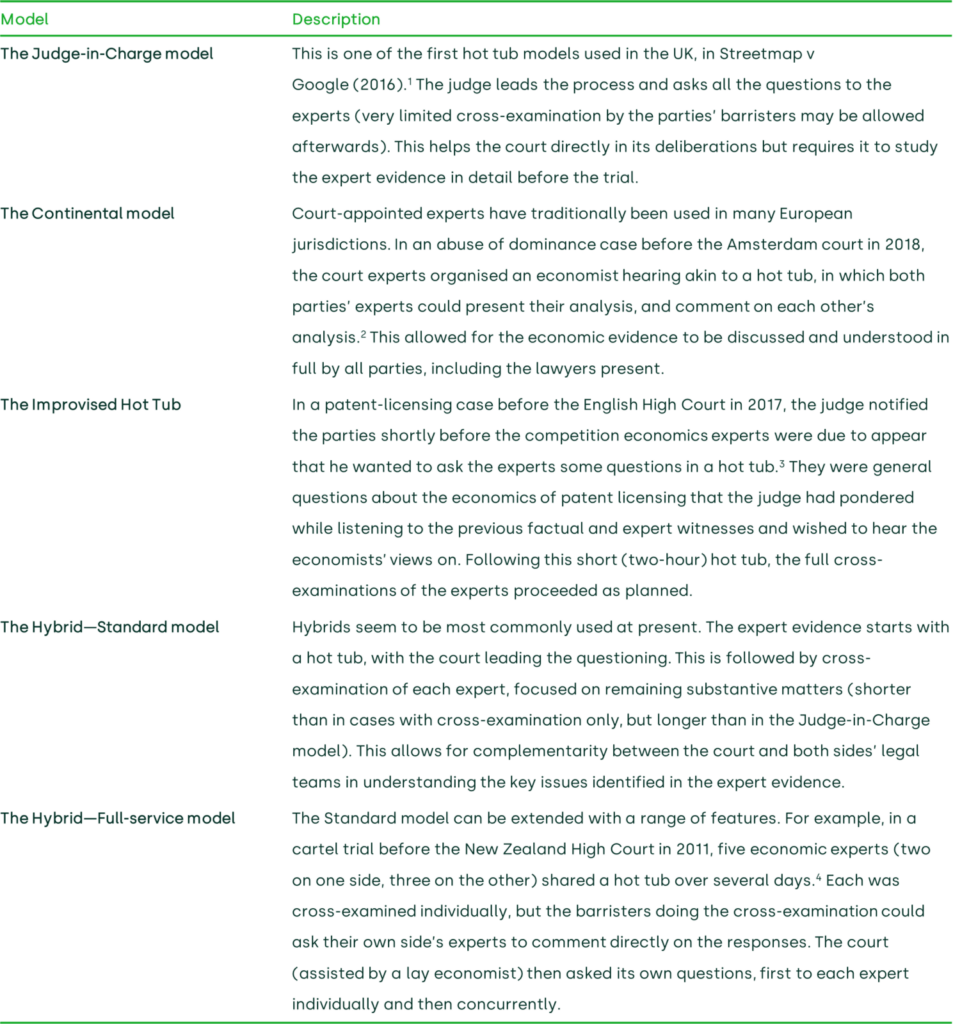

In Table 1, I provide my own classification of expert hot tubs, based on Oxera’s experience in various jurisdictions.

Table 1 The expert hot tub catalogue: pick your favourite model

Source: Oxera.

The expert hot tub can be a useful method to test and clarify the economic evidence. It is best seen as a complement to cross-examination—as in most of the variants in Table 1—not a substitute. There will always be aspects of the expert evidence that can be addressed and questioned more effectively by the opposing legal team (with support from the opposing expert) than by the court, since the latter will necessarily have spent less time going through the evidence before the trial.

A potential downside of hot tubs, however, is the risk that they will become ‘debating contests’, where skills of persuasion and wit matter more than substance. The experts risk being seen as ‘mud-slingers’, especially where they have already produced a joint statement of points of agreement and disagreement and the hot tub focuses on the latter. In my experience, such risks can be mitigated if the experts behave professionally and engage in the substance, in line with their duty to help the court.

Court experts, and economists as judges

Jurisdictions such as Canada, Finland, Hong Kong, Ireland, New Zealand and South Africa also use mainly party-appointed experts, as do international arbitrations. Other jurisdictions often rely on court-appointed experts. These assist courts in making their decisions, sometimes sitting alongside a judge in the courtroom. Some specialised courts, such as the Competition Appeal Tribunal (CAT) in the UK and the Competition Tribunal in Canada, even have economists among their ‘lay members’. CAT panels often consist of two judges and an economist—one of Oxera’s founders was a lay member of the CAT for a number of years.

It need not be that more objective outcomes are obtained if the expert is appointed by the court rather than the parties. Courts in Australia have noted that it is not inherently bad if party-appointed experts do not reach the same conclusion, especially in a field such as competition law. As one Australian judge stated: ‘The fallacy underlying the one-expert argument lies in the unstated premise that in fields of expert knowledge there is only one answer.’5 Another noted that it can be useful to have contradictory evidence because the court does not normally choose between the experts, preferring all aspects of one opinion over another, but rather uses these differing views to assist in reaching its own conclusion.6 Economic theory has also pointed to the advantages of adversarial systems (comparable with a system of party experts) over inquisitorial systems (comparable with a system with a court expert), in particular as regards the quantity of information and analysis provided, and hence the quality of the decision-making.7

Concluding remarks

Both systems—party- and court-appointed experts—can work well, provided that they meet the criteria identified above. One is that the evidence is properly tested. Even court experts should have their analyses tested by the parties and their experts. Likewise, court experts must talk to the party experts, exchange analyses, and seek to narrow the issues under consideration. In all, allowing experts to explain their evidence, subjecting them to cross-examination—and possibly a hot tub—and requiring the experts on all sides to narrow the issues by identifying points of agreement and disagreement, are all part of the recipe for the successful use of economic expert evidence in court cases.

1 See The Rt Hon. Lord Justice Green’s five truisms about economists: Green, N. (2011), ‘It’s not that Complicated Really: Truisms about Economists’, Agenda, June. He praised the rigour that mathematics has brought to economics; and the mortis. I also note that a Google search for ‘lawyer jokes’ still generates ten to 15 times more results than ‘economist jokes’.

2 The Racecourse Association and the British Horseracing Board v OFT [2005] CAT 29, Judgment of 2 August 2005, at [167].

3 BSkyB Limited and Sky Subscribers Services Limited v HP Enterprise Services UK Limited (formerly Electronic Data Systems Limited) and Electronic Data Systems LLC (formerly Electronic Data Systems Corporation) [2010] EWHC 86 (TCC), Judgment of 26 January 2010, at [303].

4 Rares, S. (2013), ‘Using the “Hot Tub”: How Concurrent Expert Evidence Can Help Courts’, Agenda, November.

5 Downes, G. (2006), ‘Problems with Expert Evidence: Are Single or Court-appointed Experts the Answer?’ Journal of Judicial Administration, 15:4, p. 185.

6 Ancher, Mortlock Murray & Woolley Pty Ltd v Hooker Homes Pty Ltd [1971] 2 NSWLR 278, at [286E-F].

7 See, for example, Shin, H. (1998), ‘Adversarial and inquisitorial procedures in arbitration’, RAND Journal of Economics, 29:2, pp. 378–405.

Related

Access to land for mobile telecoms networks: a framework for negotiation and regulation

Mobile towers serve as the backbone of mobile telecoms networks, hosting radio access network equipment that enables us to receive calls, texts and to access the internet on our mobile devices. In turn, the ability of the builders of mobile towers to access land—whether that is on the ground,… Read More

Measuring and inferring anticompetitive effects from an exchange of information

In four rulings1 dated 3 November 2025, the Spanish National Court overturned the Decision of the Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia (CNMC) in case S/DC/67/17 Tabacos2 (‘the Decision’). These four rulings are significant because they close one of the first cases that the… Read More