How will COVID-19 affect reform of the energy retail sector in Italy?

Lockdowns related to the COVID-19 pandemic have had a significant impact on the energy sector. Italy was the first European country to be significantly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and is gradually moving back to normality. In a previous piece, we covered the pandemic’s effect on the UK electricity market; here, we consider the effect on the Italian electricity market.

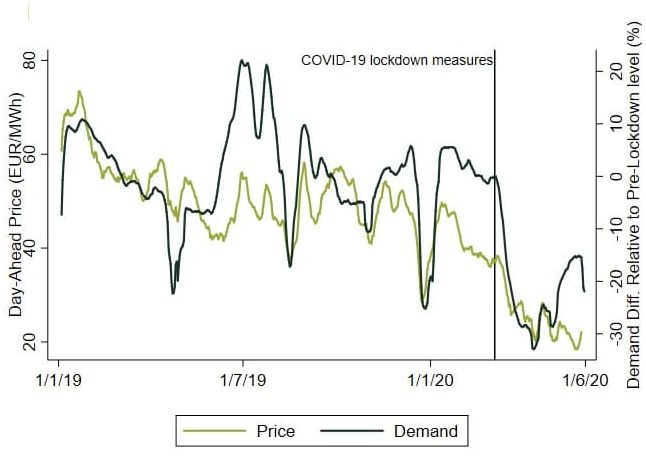

ENTSO-E market data collected during April and May 2020 shows that, in Italy, the total demand for electricity has fallen by around 25% due to very strict lockdown measures.1 While domestic demand has increased as a result of the lockdown, industrial demand has plummeted, outweighing the former effect. Fluctuating demand, in combination with the availability of electricity supply, has caused significant variation in in the wholesale electricity prices in the day-ahead market.

Figure 1 Combined industrial and domestic electricity demand and electricity day-ahead prices in response to lockdown restrictions

Source: Oxera analysis based on data accessed via the ENTSO-E Transparency Platform.

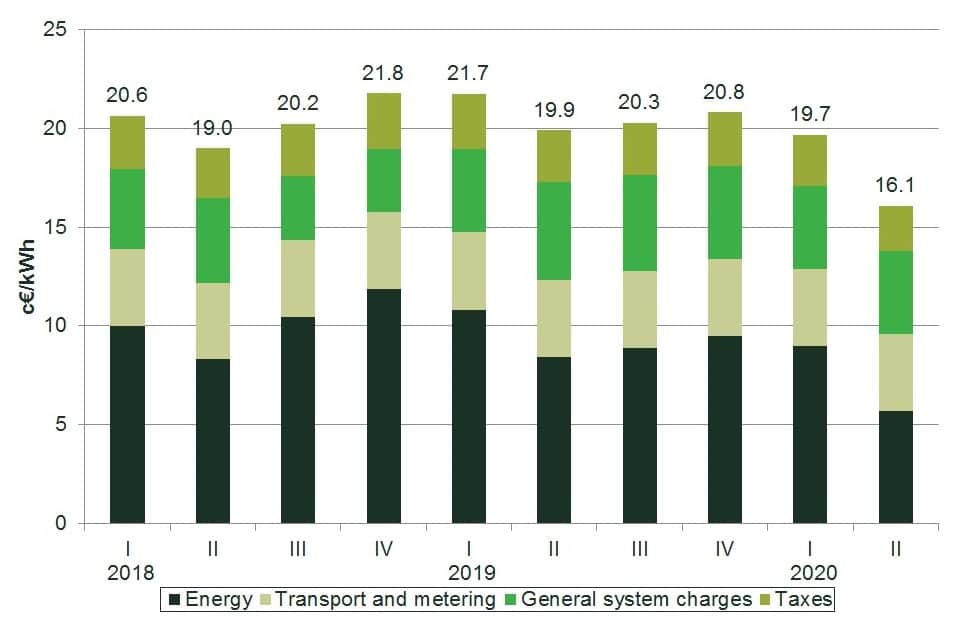

Italy’s national energy regulator, ARERA, provided a detailed breakdown of the evolution of overall electricity prices. For a representative household, prices have decreased by 5.4% in the first quarter of 2020 and by 18.3% in the second quarter, compared to the same quarter in 2019.

Figure 2 Electricity costs for a representative Italian household, 2018 Q1–2020 Q2 (€cent/kWh)

Source: ARERA.

The ‘energy component’, which includes generation and retail costs and represents the largest component—35.5% of the overall representative bill—has experienced a large decrease, 32.1%, in Q1 2020 (compared to Q2 2019) as a result of market dynamics. On the one hand, the single wholesale electricity price for Italian consumers (‘prezzo unico nazionale’, PUN) has dropped as a result of low consumption and renewables becoming more central.2 On the other hand, the electricity TSO (Terna) had to intervene in the re-dispatching market to overcome system imbalances, which resulted in record high re-dispatching costs in March.

Despite the significant drop in prices, the Italian government and, in turn, ARERA have put in place a series of affordability measures to help vulnerable end-customers.

Has the COVID-19 crisis affected the retail regulatory processes in place in Italy?

First, following a Decree from the Prime Minister in March, ARERA suspended electricity and gas bills for the areas of Italy subject to the most stringent mobility restrictions, with the obligation to automatically defer bill payments. Second, ARERA gave more relaxed timescales for consumers to obtain access to their so-called ‘bonus’ (a tariff discount for low-income families and consumers in need), considering the practical difficulties of submitting an application for renewal during lockdown. Third, all procedures for the disconnection of family and small-business electricity, gas and water supplies due to arrears were postponed. Finally, a fund has been set up with the Energy and Environmental Services Fund (CSEA), with resources amounting to €1.5bn, to finance regulatory measures that support consumers and users.

In sum, during the crisis, ARERA has intervened with a strong emphasis on consumer protection. The crisis has occurred in the midst of a trend of slow but steady liberalisation of the Italian energy market, and it is unclear whether and to what extent this unforeseen ‘shock’ might delay this process further.

After a series of postponements, the Italian government decided to set the end of the ‘regulated’ retail electricity and gas markets at January 2021 for small enterprises, and at January 2022 for micro-enterprises and domestic customers. As indicated by the government, retail customers in the regulated segment (the so-called ‘maggior tutela’) will be gradually transitioned into the free market. Over the course of the transition, ARERA will have to prevent excessive prices and ensure that customers continue to enjoy the same economic conditions that they experienced under the fully regulated regime.

It is expected that the transition will take place by means of ‘auctions’, as a result of which ‘lots’ of customers will switch to winning retailers. ARERA will be in charge of designing the auction rules and overall framework. An initial consultation paper, published in September 2019,3 set out ARERA’s early thinking on how these auctions will be designed in relation to the participation requirements for retailers, the high-level features of individual ‘lots’ of customers, and the post-auction economic conditions that customers will be subject to. ARERA’s stated objective was to ensure that the liberalisation of the market takes place with the full awareness of the end-consumers and without distortions to competition.4

In this context, considering the degree of uncertainty brought about by the COVID-19 crisis, there is an open economic question as to how retailers will respond to the auctions and how the transition to a fully liberalised market will unfold.

While ARERA has yet to provide information on recent retail market developments, the most recent monitoring report provides a good indication of long-term trends and can help to identify some open questions with a view to full market liberalisation in this uncertain context.

Retail market concentration

Over recent years, the number of new ‘retailers’ at the national level has increased considerably, which has resulted in a significant number of operators being active across all or almost all Italian regions.

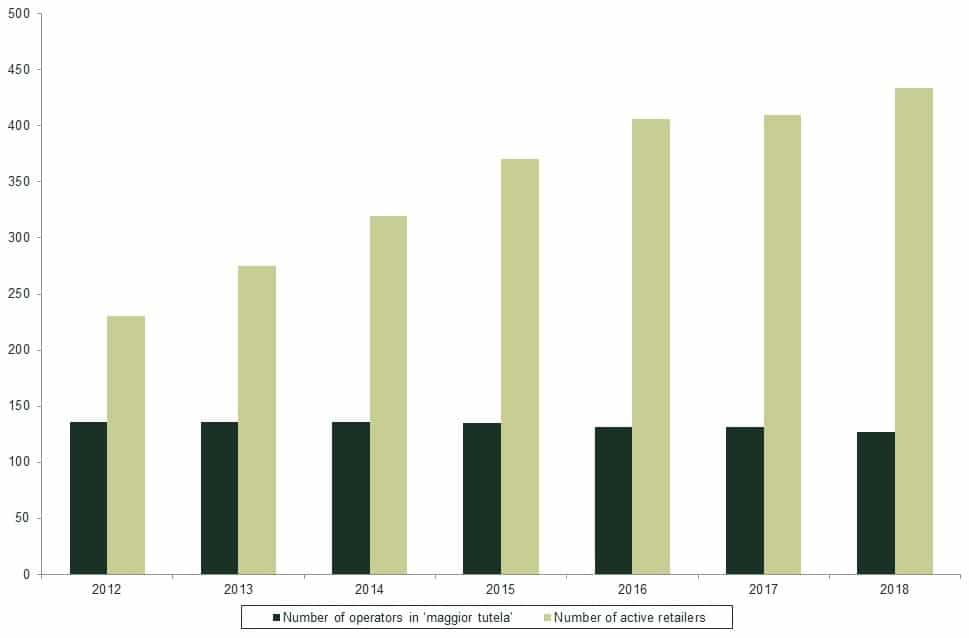

Figure 3 Number of retailers in Italy, 2012–18

Arguably, this trend has been the result of low barriers to entry and a generally dynamic market. In 2018, overall market concentration decreased compared to 2017, as measured by the CR3 (the market share of the three largest firms) and the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI).5 Even in the absence of direct interventions on the retail market structure that may result from retail ‘auctions’, market forces have seemed to at least partially drive the liberalisation process.

The impact of COVID-19 is yet to be seen, although stakeholders recently argued that in the absence of significant financial support, a prolonged negative shock may result in small retailers exiting the market.6

Interestingly, market concentration varies across different segments. For example, in 2018, CR3 (based on energy volumes) was around 67% for domestic customers, 36% for small enterprises (‘bassa tensione’), and 31% for medium enterprises (‘media tensione’).7 In this respect, it is interesting to see that the legislator will intervene first in a relatively more ‘dynamic’ market—which perhaps requires the least intervention, as consumers are arguably more informed and able to ‘switch’ as a result of more advantageous offers.

While the presence of a large number of small suppliers may introduce competitive pressures to the benefit of consumers, it may also raise potential consumer-protection issues (for example, due to the number and complexity of retail offers, retailers may take advantage of consumer ‘biases’ to maximise profits). For this reason, any decision about reform should take account of market ‘outcomes’—that is, transparency, existing customer satisfaction, and company reliability both in terms of quality of service and financial stability.

Switching rates in the retail market

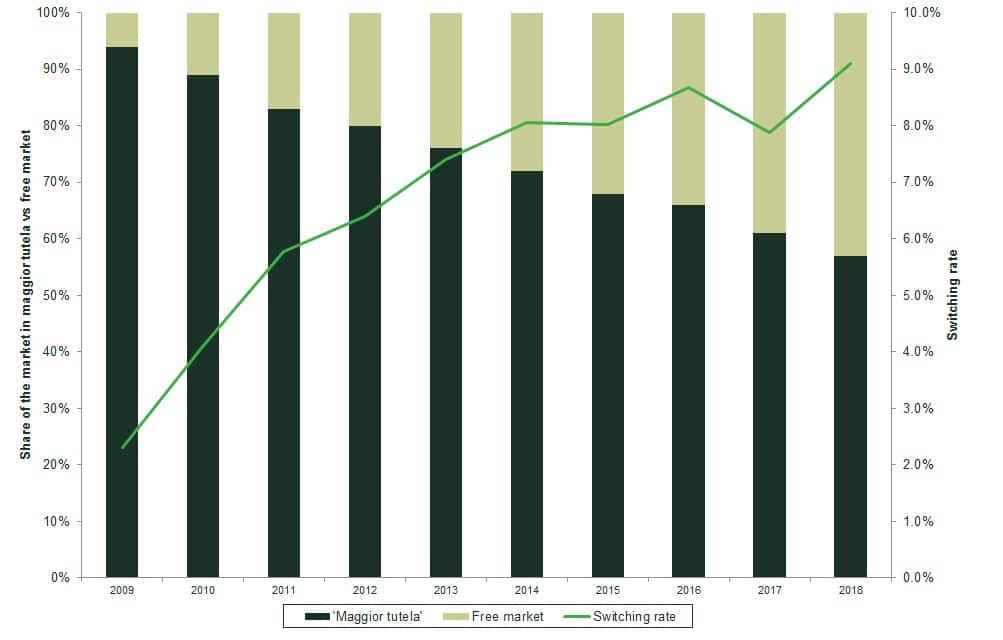

Despite some delays in market reform, Figure 8 shows that customers have indeed migrated from the ‘regulated market’ to the ‘free market’ over recent years. More recent data is yet to be made available.

Figure 4 Switching rates and share of liberalised vs regulated markets, domestic customers, 2012–18

For domestic customers, the share of customers in maggior tutela went from 94% in 2009 to 56% in 2018. For small enterprises, it is possible to observe a similar trend, with the ‘regulated’ market amounting to 43% in 2018.8

The rate at which consumers switch from one retailer to the other has also been subject to a long-term positive trend for domestic customers. In 2018, the switching rate was at a record high, at 9.1%. For non-domestic customers, switching rates are significantly higher, i.e. 17.2% (30.2% if limited to medium tensione) in 2018. It is difficult to assess whether the switching rates will be significantly affected by COVID-19. In the medium term, the worsening of economic conditions (and decrease in energy costs) might lead consumers to seek better offers and be more ‘proactive’.

This would require an investigation of the reasons why some customers in maggior tutela have decided not to switch to date. On the one hand, it may be argued that a ‘regulated price’ may have so far been effective in offering sufficient protection and good terms for customers relative to market offers. This may call for a cautious approach to liberalisation, which may perhaps be reflected in the conditions under which the retail ‘auctions’ will take place (e.g. ensuring that auction outcomes do not lead to abrupt changes in the economic conditions enjoyed by customers in maggior tutela).9 On the other hand, the presence of a significant share of customers in maggior tutela may reflect inertia and limited knowledge of more convenient conditions in the market, which may call for further measures to raise consumer awareness.

General system charges: further strain on the energy value chain

The COVID-19 crisis will have broader repercussions for regulatory processes, with a direct impact on consumers. For example, the ‘general charges’ component in Figure 6 has been subject to extensive political debate.

‘General system charges’ (or ‘oneri di sistema’) represent a significant component of the final bill. In the second quarter of 2020, these charges amounted to 26% of overall energy costs. These reflect general charges to support renewable energies and co-generation, as well as other charges to support the energy systems.10

The process for recovering such charges is highly complex. Retailers are to recover the amount due from customers and transfer it to distributors, which in turn should transfer it to two public entities in charge of managing the resources.11 The legal responsibility for recovering general system charges has been subject to a number of court cases, which so far appear to have indicated that final customers are ultimately responsible for any missing payment.

The ability to recover the amounts associated with this component from customers becomes particularly relevant in this uncertain context, which is presumably characterised by higher delinquency rates. Stakeholders have proposed a greater intervention by a public entity (e.g. Acquirente Unico) to be in charge of collecting such charges directly from retailers and address ‘bad debt’ issues from both retailers and final customers.12 In the past, ARERA expressed a preference for a gradual reform that would change the nature of ‘general charges’ from a tariff component to a ‘tax’.13 The size of this item on final customer bills has so far impacted consumers’ perceptions about the extent of saving opportunities in the retail market.

Conclusion

The 2019 European Directive 2019/944 sets out an ambitious objective of full retail electricity market liberalisation.14 At the same time, it envisages specific derogations for energy-poor and vulnerable household customers, and it allows for time-limited public interventions in price settings.

In Italy, the COVID-19 crisis and recent emphasis on consumer protection may lead to an increased focus on supplier reliability and service-quality issues. With a view to retail auctions, it will be important to ensure that potential bidders are sufficiently reliable and financially stable to provide retail services. More broadly, as indicated by a number of industry stakeholders, the sector may need a more effective tool to ensure that electricity retailers comply with specific technical, financial and integrity requirements. The legislator aimed to address this by creating a ‘supplier register’ (or ‘albo fornitori’)15 to be published and reviewed by the Minister of Economic Development; however, this is yet to be introduced.

1 Clair, E. (2020), ‘Looking at Covid-19 crisis from the EU electricity wholesale market’, European University Institute, April.

2 From 53,4 €/MWh to 24.8 €/MWh. Terna (2020), ‘Rapporto mensile sul Sistema Elettrico’, April.

3 ARERA (2019), ‘Documento Per La Consultazione 397/2019/R/EEL’, September.

4 ARERA (2019), ‘Quadro Strategico 2019-2021’.

5 ARERA (2019), ‘Relazione Annuale Stato Dei Servizi’, March, p. 127.

6 For example, see Staffetta Quotidiana (2020), ‘Retailer energia, Arte: intervenire, non reggiamo oltre giugno’, June.

7 ARERA (2019), ‘Monitoraggio Retail. Rapporto per l’anno 2018. Rapporto 527/2019/I/com’.

8 ARERA (2019), ‘Monitoraggio Retail. Rapporto per l’anno 2018. Rapporto 527/2019/I/com’, p. 34.

9 ARERA (2019), ‘Documento Per La Consultazione 397/2019/R/EEL’.

10 For example, the cost of dismantling decommissioned nuclear power stations, incentive costs for production from non-biodegradable waste, tariff-protection measures for customers, and research and development costs for technological innovation.

11 Cassa per i servizi energetici e ambientali (CSEA) and Gestore dei servizi energetici (GSE).

12 Utilitalia (2020), ‘Affare Sulla Razionalizzazione, La Trasparenza E La Struttura Di Costo Del Mercato Elettrico E Sugli Effetti In Bolletta In Capo Agli Utenti’, June.

13 ARERA (2018), ‘Memoria 20 Novembre 2018 588/2018/I/EEL’. ARERA (2020), ‘Memoria 175/2020/I/COM’.

14 Official Journal of the European Union (2019), ‘Directive (EU) 2019/944 Of The European Parliament And Of The Council of 5 June 2019’, June.

15 The ‘supplier register would authorise electricity retailers to operate only if fully compliant with a set of industry-wide standards.

Download

Related

Future of rail: how to shape a resilient and responsive Great British Railways

Great Britain’s railway is at a critical juncture, facing unprecedented pressures arising from changing travel patterns, ageing infrastructure, and ongoing financial strain. These challenges, exacerbated by the impacts of the pandemic and the imperative to achieve net zero, underscore the need for comprehensive and forward-looking reform. The UK government has proposed… Read More

Investing in distribution: ED3 and beyond

In the first quarter of this year the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC)1 published its vision for the UK’s electricity distribution network. Below, we review this in the context of Ofgem’s consultation on RIIO-ED32 and its published responses. One of the policy priorities is to ensure… Read More