The puzzle of regulating pay: practical solutions for firms and supervisors

Implementing new regulatory standards for remuneration is challenging for the financial services sector. What are the underlying issues, and how can firms deal with them effectively? Peter Andrews, Senior Adviser, and Jonathan Haynes, Senior Consultant, explain the issues and propose some practical tools for firms and regulators.

Regulating remuneration is challenging—for both regulators and firms. This is particularly the case in financial services.

The scope of regulation on remuneration is broad. Historically the focus has been on public disclosure and transparency, mainly for listed companies—with standards set primarily via corporate governance codes of conduct and listing rules.

Since the global financial crisis that began in 2007, there has been greater consideration of the impact that compensation and related performance-management mechanisms can have on risk-taking and the long-term health of financial institutions. In 2009, the G20 and the Financial Stability Board (FSB) agreed international standards, which were latter embedded within legislation at the European level.1 Regulatory reform included rules linking total bonus pools to the financial performance of the relevant business units, and public disclosure and transparency requirements. There have also been reforms to shareholder powers over pay, and a high-profile cap on banker bonuses.

This article examines the importance of regulating remuneration in financial services, and advocates an approach to overcome the challenges of supervising pay using traditional economics, behavioural insights, and machine-learning.

Separation of ownership and control

Rarely is the owner of a large firm one and the same as the person who runs it. This separation of ownership and control is one example of the principal–agent problem—i.e. the objectives of the agent may differ from those of the principal.

There are several reasons why management may not act in the best interests of the owner. For example, management may engage in:

- insufficient effort—i.e. allocate work time to non-core business tasks;

- extravagant investments—i.e. invest in pet projects and empire-building to the detriment of shareholders;

- entrenchment strategies—i.e. invest in lines of activities that make the management indispensable, manipulate performance measures, or resist hostile takeovers;

- self-dealing—which could range from benign to illegal activities.

The principal–agent problem can be addressed by aligning the incentives of managers with those of owners. One way to do this is via remuneration structures that are intended to reward management for achieving outcomes that are in the owners’ interests. Examples include options and performance-related pay metrics.

However, in financial services we have seen that these incentives need careful design. On the one hand, if incentives are insufficiently high-powered, they are unlikely to have a significant impact on managers’ behaviour. On the other hand, high-powered incentives may create unintended consequences, including excessive risk-taking, a disproportionate focus on those aspects of performance that are incentivised (to the detriment of others), and/or short-termism.

Since the global financial crisis there has been increased focus on the regulation of remuneration, as a direct result of the causes of the crisis. In line with the hypothesis that managers need to be incentivised in order to make an effort, many firms designed employment contracts to award managers with higher pay for generating additional profits. But contracts were less successful at incentivising managers to generate profits without taking large risks. From a manager’s perspective, this resulted in decisions to take risks with highly asymmetric consequences: heads, they won; tails, their employer lost.

Moreover, given the nature of the financial services sector, the decisions taken by managers had the potential to negatively affect wider society, and not just investors. Avoidance of such negative externalities is a major goal of financial regulation—and justifies intervening in relation to remuneration.

Regulators have tried to address short-termism by requiring firms to replace cash bonuses paid immediately to managers with equity stakes that can be realised at different points in the future. There is a paradox here: while equity-based bonuses may help to address the time dimension problem, they may also exacerbate the risk dimension problem.2

Another major issue in financial regulation has been widespread non-compliance in some sectors. This is likely to be due to a mixture of cultural, behavioural and incentive-based causes. To bring about substantive change, it is important to address all of these. We believe that these well-designed and well-implemented remuneration packages that align employees’ incentives with owners’ interests will also encourage regulatory compliance, and that this will be critical to the success of the regulatory regime as a whole.

Practical solutions for firms

The job of the firm is to set remuneration policies to recruit, retain and motivate staff in line with its business strategy. It is not in the interests of firms or their owners to pay employees more than they are worth for a sustained period. Likewise, it is not in a firm’s interests to encourage staff to take unsustainable or reckless risks with its money or reputation. However, there should be sufficient incentives for staff to contribute a serious effort in the interests of the firm. By setting sound remuneration policies, a firm can motivate staff in line with its business objectives.

In practice, firms influence the discipline and control of their employees via contract design and formal structures (within firm governance and control). Informal elements are also important to help determine standards and culture. Key elements of this include standard-setting, codes of conduct, remuneration structures, qualification and training, compliance and whistleblowing policies, and accountability rules.

In some industries, professional bodies have an important and sometimes leading role in the exercise of control over individuals within the profession. Standards based on the code of conduct and the required qualifications are set, and given force by the fact that breaches can result in disciplinary action, up to and including exclusion from the profession.

As noted above, there are international FSB standards for regulation of remuneration. When designing or reviewing remuneration policies and practices, firms should consider the conduct of business and conflict of interest risks that may arise.

The challenge for firms, and particularly the Board and senior managers,3 is to comply with these standards in an effective manner while avoiding needless bureaucracy and costs.

In designing its approach to remuneration, the firm needs to be careful about its reaction to competition for talent and consider the overall incentives for managers to comply with its policy, rather than considering narrow issues regarding remuneration. The external market, including competition, may provide incentives to comply or incentives not to do so. Likewise, a firm’s internal controls are vital. If firms have in place strong controls (usually overseen by non-executive Board members in audit and risk committees), problems are less likely to emerge over time.

A remuneration plan crafted to strike the right balance between motivation, profits, ethics and compliance will fail if other incentives for bad behaviour remain. For example, if a firm says it will pay no bonuses for non-compliant sales but also dismisses staff who do not meet challenging sales targets, or, less extremely, sends such staff on all-weekend re-training exercises in unattractive locations, it may well find that significant, non-compliant sales continue. Contracts that expose managers to some losses may help.

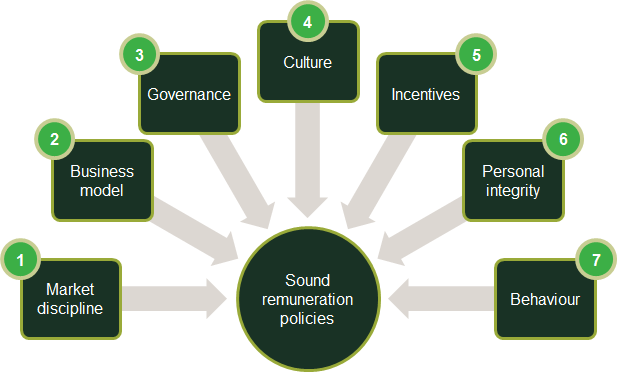

Consequently, firms should analyse, set and review their remuneration arrangements in a holistic way. We believe that the best way of doing so is by using the seven drivers of remuneration policies that we have developed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Seven drivers to sound remuneration policies

- Market discipline: does the market oblige firms and individuals to behave in ways that are consistent with regulatory goals?

- Business model: does this require the fair treatment of consumers and reasonable risk-taking?

- Governance: if the Board establishes a fair and reasonable business model, do governance arrangements (enforced controls) in principle ensure that the model will be followed?

- Culture: does the management and staff culture support the governance arrangements, or undermine them?

- Incentives: do remuneration and other incentives (e.g. not being fired) promote decision-making at the individual and committee level that is consistent with regulatory goals?

- Personal integrity: do staff have unblemished records of behaving with integrity, or might they misbehave even if incentives are aligned with regulatory goals?

- Behaviour: typical business models, governance (systems and controls) and incentives are designed with rational responses in mind: do they allow for realistic behavioural biases?

Approach to supervising remuneration

Like firms, regulators need to take a holistic approach to remuneration. They need to consider the environment inside and outside a company before deciding whether its approach to remuneration is adequate. The judgement must be context-specific.

Supervision of remuneration is a challenging and complex task due to the depth and breadth of firms’ policies and contracts that supervisors need to consider.

For example, take the regulation of financial services remuneration in the UK. The lead regulator, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), has a staff of around 3,500 who regulate approximately 56,000 firms. These firms have millions of employees and sell to nearly every adult in the UK. We understand that about 1,300 of the FCA’s staff are supervisors, of whom a subset will be tasked with looking at remuneration policies.4 So that’s just over 40 firms, and thousands of employee remuneration contracts, per supervisor.

The challenge for the supervisor is how to prioritise resources efficiently and effectively to ensure that remuneration policies are being set and used in ways that align the interests of firms’ owners, managers (and other staff), and customers.

Supervisors can access vast amounts of information and data about the firms that they supervise. The challenge is to know what to do with this data so that they can act efficiently and effectively. Supervisors need to decide where to focus their investigation. In the past, basic techniques such as random sampling may have been used. Nowadays, the more sophisticated supervisors are using the power of big data and machine learning to improve predictive power and to inform where to focus their magnifying glasses.5

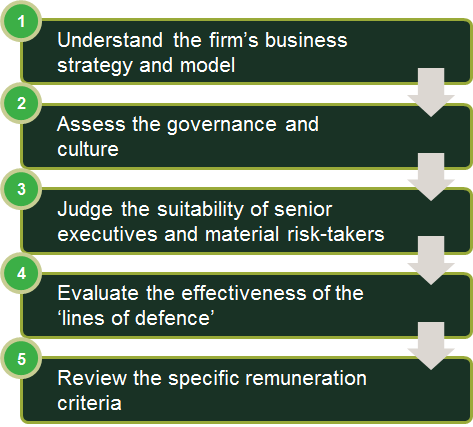

To aid this prioritisation process, we have developed a ‘five-step strategy’ for supervisors (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Supervising remuneration: a five-step strategy

In operating this strategy, typical questions that a supervisor might consider are:

- to what extent are performance bonuses adjusted after the fact to reflect conduct fines levied by the supervisor?

- to what extent are performance bonuses adjusted after the fact to reflect findings of prudential non-compliance by the supervisor?

- what proportion of people found to have been non-compliant received a performance bonus?

- what proportion of bonuses awarded to people found to have been non-compliant were greater than those awarded to people performing similar roles?

- what proportion of people found to have been non-compliant were disciplined under the firm’s HR procedures?

- were any people in serious breach of regulations dismissed?

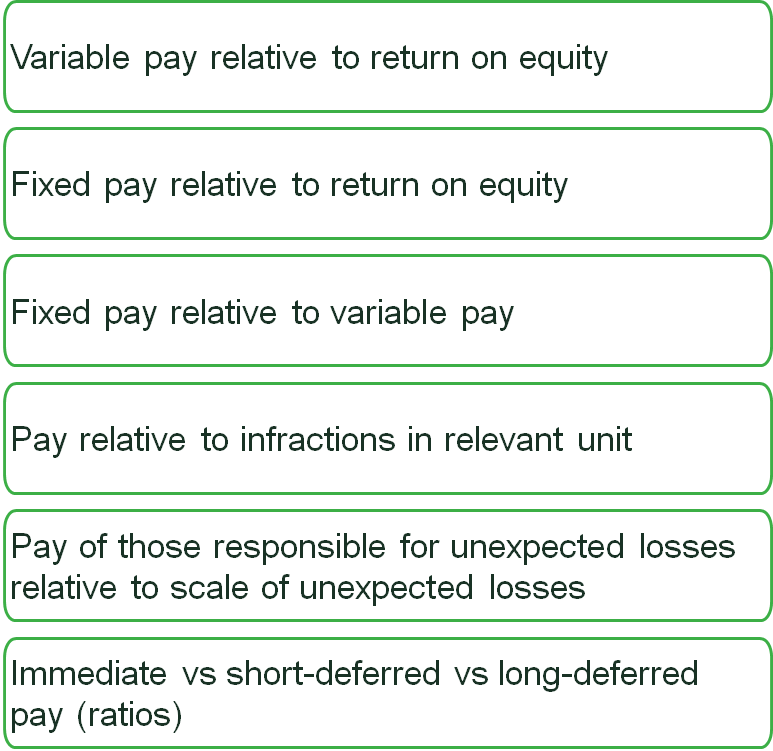

In our view, consistent application of the five-step strategy requires the use of metrics. But the situation is complex, involving many variables. We therefore believe that the metrics can usefully be fed into machine-learning algorithms that enable firms to improve their decisions about remuneration, and enable supervisors to improve their monitoring of firms’ practices in this area.

These metrics can be grouped by category of interest for further assessment, such as metrics on the scale of conduct risk, prudential risk, or responses to regulatory findings. Metrics can then be analysed at the firm or group level and be benchmarked against control groups, other sectors, or other countries.

To assist in this work, we have identified a set of useful metrics (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Example metrics

So what does this all mean going forward?

The big opportunity arising from regulating remuneration is improved compliance with the whole regulatory regime so that prudential and conduct risks are controlled.

Compliance depends on using the seven drivers of sound remuneration polices to prompt individuals to make the right decisions. The tools described here can in turn help firms and supervisors ensure sound remuneration policies that are aligned with the interests of firm owners and—crucially—end-consumers.

1 See Financial Stability Board (2009), ‘FSB Principles for Sound Compensation Practices: Implementation Standards’, 25 September; and Financial Stability Board (2018), ‘Supplementary Guidance to the FSB Principles and Standards on Sound Compensation Practices: the use of compensation tools to address misconduct risk’.

2 Economic theory suggests that equity-based variable remuneration schemes tend to increase the risk appetite of managers. For example, see Tirole, J. (2006), The Theory of Corporate Finance, Section 1.2.2, ‘Monetary incentives’, Princeton University Press, pp. 21–24; and Low, A. (2009), ‘Managerial risk-taking behavior and equity-based compensation’, Journal of Financial Economics, 92:3, pp. 470–490.

3 According to the EU’s Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID), the design of remuneration policies should be approved by senior management. Senior managers are also responsible for the implementation of remuneration policies and practices and for preventing and dealing with any relevant risks that remuneration policies can create. See European Securities and Markets Authority (2013), ‘Guidelines: remuneration policies and practices (MiFID)’, ESMA/2013/606 guidelines, 1 October.

4 Source: Financial Conduct Authority Annual Report and Accounts 2017/18, Table 2.

5 Hunt, S. (2017), ‘From maps to apps: the power of machine learning and artificial intelligence for regulators’, speech, Financial Conduct Authority, 22 November.

Download

Related

Switching tracks: the regulatory implications of Great British Railways—part 2

In this two-part series, we delve into the regulatory implications of rail reform. This reform will bring significant changes to the industry’s structure, including the nationalisation of private passenger train operations and the creation of Great British Railways (GBR)—a vertically integrated body that will manage both track and operations for… Read More

Cost–benefit analyses for public policy

Cost–benefit analyses (CBA) are commonly applied to public infrastructure projects where there is a degree of certainty about the physical output of the project and the consequent societal benefits. CBA can also be applied to proposed policy and regulatory changes, but there is less clarity about the outcomes and the… Read More