They think it’s all over… Economic dynamics behind the European Super League

The announcement of the European Super League (and the subsequent climbdown) has attracted attention across the globe. As discussed in this article, the Super League forms part of a wider narrative of changing football audiences and the difficult decisions that clubs face when monetising them.

The announcement that 12 of the wealthiest football clubs in Europe were planning to join a breakaway ‘European Super League’ (ESL) stirred controversy across the globe.1 In the days following the announcement, many of the 12 clubs withdrew from the ESL, and some issued statements apologising to their fans.2

As well as provoking questions about who football ‘belongs’ to, the announcement has put the spotlight on the sustainability of the football ‘business model’ and reopened discussions around football’s relationship with competition law.3

It has been argued, for instance, that the ESL resembles a cartel, with its founding members seeking to protect TV revenues by limiting entry and ensuring that they stay in the league without needing to qualify each year.4 It has also been argued that the threat of retaliation made by UEFA (the confederation of European football associations) against these clubs amounts to an abuse of dominance, given that UEFA currently holds a monopoly over European football leagues—indeed, a Spanish court ruling has sparked a European Court of Justice case on the subject.5

While a competition assessment might be of interest, this article focuses on the overall market dynamics in football and the impact that this is having on the game. Our analysis shows that the ESL is part of a wider story of changing football audiences, the evolution of demand for European football, and the attempts of football clubs to adapt to and monetise this demand.

Although this article focuses on football, these debates and tensions around how best to organise and monetise sports are relevant for a wide range of competitions, from Formula 1 to boxing, and from speed skating to darts.

It’s coming home

Before matches were routinely televised, football clubs tended to generate revenues locally, relying mainly on matchday revenues. As such, the audience for a given football game was effectively limited to the people in attendance, with a number of supporters listening to the match on the radio.

As increasing numbers of games began to be televised, a club’s audience extended beyond those who attended the games. The ability to follow the action was of high value to a number of supporters,6 and the larger audience allowed clubs to earn revenues through broadcasting rights, which has dramatically increased their income. For instance, the amount distributed by the English Premier League (itself a ‘breakaway’ league of sorts) to clubs for TV rights increased from just under £42m in 1992 to £1,013m in 2010 (i.e. by a factor of 24 in less than two decades).7

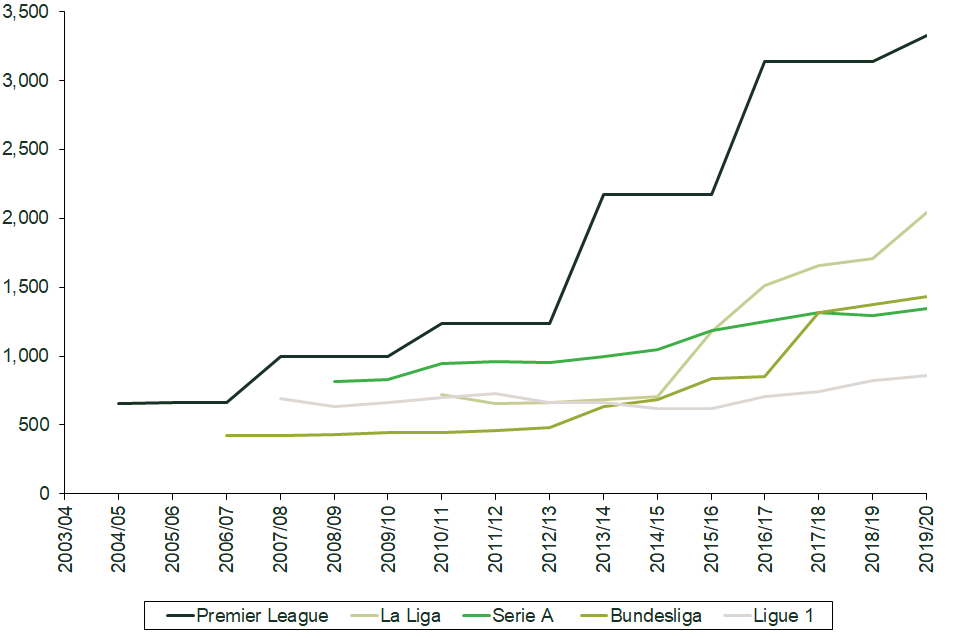

Revenues for all the major European leagues have increased significantly, largely due to broadcasting rights management. Figure 1 shows the revenues from broadcasting rights (both domestic and international) across the five largest footballing leagues. For all five, broadcasting revenues have been increasing, although the Premier League has seen the most dramatic increase.

Figure 1 Total TV rights revenues, Big Five national leagues (€m)

Source: Oxera analysis based on multiple sources.

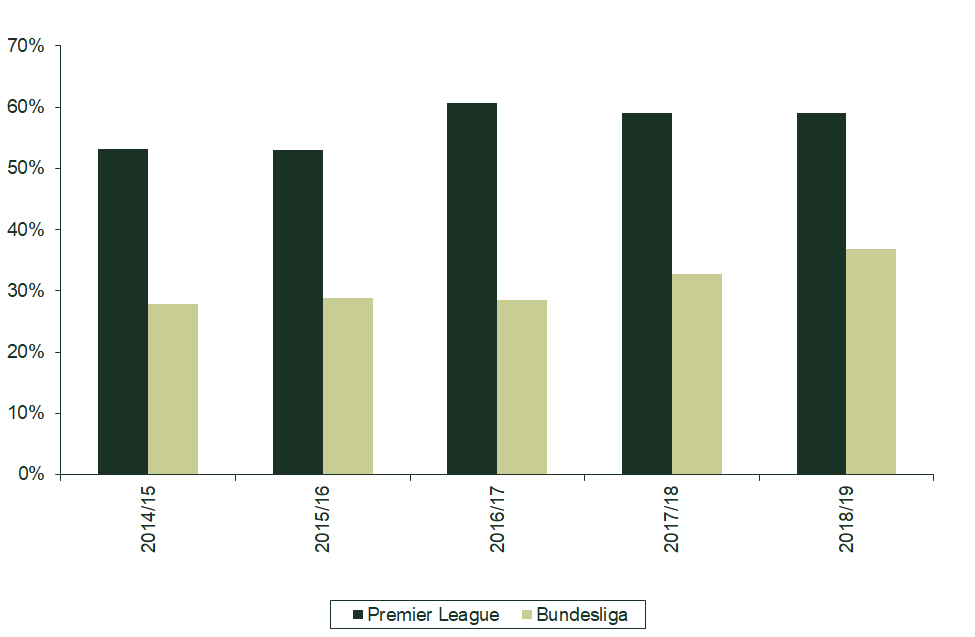

Due to the rapid expansion of the value of sales for football clubs and their leagues, broadcasting revenues now account for a significant proportion of clubs’ overall income. As set out in Figure 2, broadcasting revenues account for more than 50% of Premier League revenues, and they are becoming increasingly important in the Bundesliga—accounting for over 30% of revenues in 2018/19.

Figure 2 Broadcasting revenue as percentage of total revenue of Premier League and Bundesliga from 2014/15 season to 2018/19 season

Source: Oxera analysis based on multiple sources.

These growing TV audiences have accompanied growing revenues from commercial operations such as sponsorship and merchandising. The more people who watch and support a particular club, the more merchandise it can sell, and the more valuable sponsorship is.

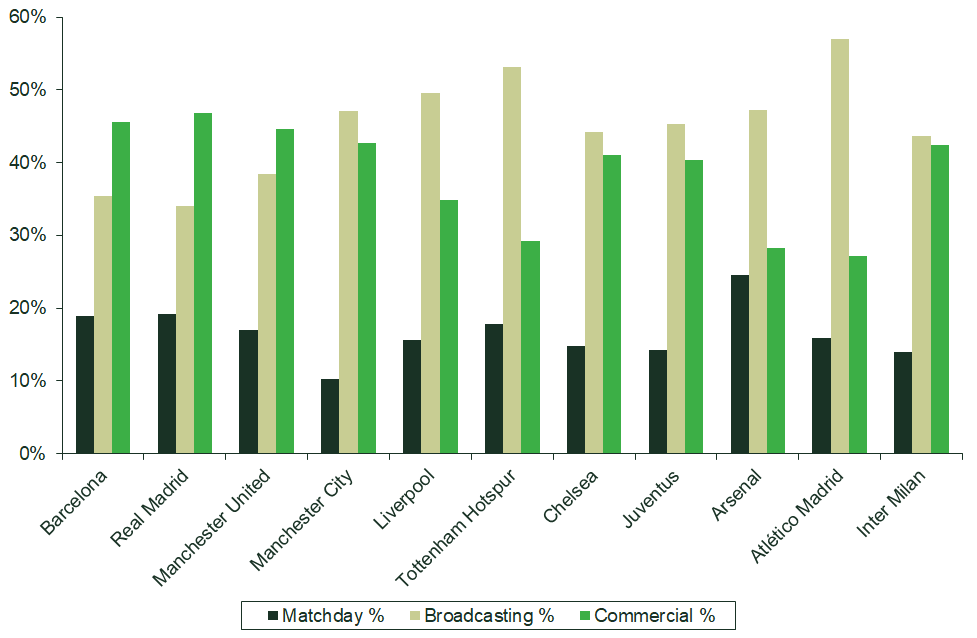

Taken together, broadcasting revenues and revenues from commercial operations now account for the majority of revenues for the 12 founding clubs of the ESL (where data was available—see Figure 3), while matchday revenues now generally account for less than 20% of revenues.

Figure 3 Distribution of revenues for 11 of the 12 ESL founding clubs

Source: Oxera analysis based on Deloitte (2020), ‘Eye on the prize: Football Money League’, January.

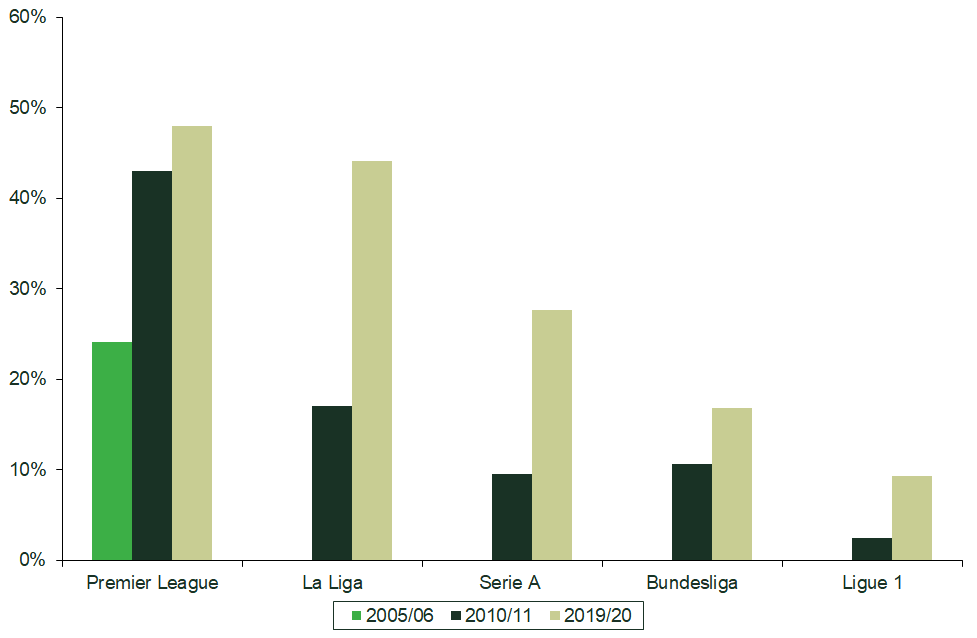

Most relevant for the case at hand is the growth of clubs’ international audiences. As shown in Figure , the share of revenues generated from international TV rights has grown materially across the Big Five leagues since 2004. For the Premier League and La Liga in particular, international broadcasting rights now account for nearly 50% of total broadcasting revenues. If these trends continue, international TV rights revenues could ultimately generate the majority of clubs’ revenues.

Figure 4 Share of international rights in total TV rights revenues, Big Five national leagues

Source: Oxera analysis of multiple sources.

The growth in international TV broadcasting revenues comes partly from within Europe, but also from relatively ‘new’ markets such as Asia and the USA. These new markets, consisting of fans outside of Europe, already accounted for 37% of the Premier League’s total broadcasting revenues in 2016.8

What does this mean for football?

The geographic reach of football clubs has increased dramatically as a result of television. International audiences now exceed the local audience in terms of revenue and, if trends continue, are likely to outgrow national audiences.

As clubs seek to maximise revenues from these international audiences, there will inevitably be trade-offs between these fans and the preferences of local (or so-called ‘legacy’) fans. In this context, there are two things to note.

First, these trade-offs are not new in football. Traditionally, football matches would be played at the weekend at a set time in the early afternoon—for example, in England, football would be played at 15.00 on a Saturday. This was not an issue when each club relied on local fans, as each club’s fans would travel to their games. However, as games began to be televised, the incentives grew to ensure that matches were spread out across the weekend, ensuring that as many viewers as possible could tune in to games from the comfort of their own homes—and thereby maximising potential revenues for the clubs.

Second, clubs will continue to face difficult decisions and trade-offs in the future. The ESL could be seen as an attempt by clubs to cater to as many international fans as possible. A recent survey found that 92% of East Asian football fans support one or more of the 12 ESL founding clubs.9 Given that the ESL would have meant these teams playing each other more often, it would also have increased broadcasting revenues for these clubs.

Although the ESL may have failed in its current form, this remaining untapped international demand means that it is very unlikely to be the last time that football clubs face difficult decisions about how best to cater to their different audiences and monetise their sport.

1 For example, see Kuper, S. (2021), ‘Super League would break football’s essential promise’, Financial Times, 19 April.

2 The announcement of the ESL received extensive coverage across major European newspapers, including: Ahmed, M. (2021), ‘“It was utter chaos”: the inside story of football’s Super League own goal’, Financial Times, 23 April; Oddenino, G. (2021), ‘Super Lega, la Juve non rinuncia e denuncia: “Pressioni inaccettabili”’, La Stampa, 8 May; Albert, E. (2021), ‘Après le fiasco de la Super Ligue, Londres met le football anglais sous pression’, Le Monde, 22 April; Moñino, L. J. (2021), ‘La gigantesca batalla legal de la Superliga’, El Pais, 20 April; Jackson, J., Ames, N. and Hunter, A. (2021), ‘Manchester United and Liverpool plead for forgiveness for Super League fiasco’, The Guardian, 21 April; Dobbert, S. and Lorenzmeier, S. (2021), ‘The Europeanization of Football’, Zeit Online, 13 April.

3 For example, see Wilson, J. (2021), ‘There are no easy answers to how football tackles its unloved billionaire owners’, The Guardian, 8 May; and Ronay, B. (2021), ‘Football’s fan protests are a positive, legitimate response to deeper discontent’, The Guardian,7 May.

4 Financial Times (2021), ‘European Super League: breakaway should ring antitrust alarm bells’, 19 April.

5 See Reuters (2021), ‘Madrid judge asks top EU Court to decide on Super League legality’, 13 May; Gabilondo, A. (2021), ‘El conflicto de la Superliga llega al Tribunal de la Unión Europea’, 12 May.

6 As illustrated by the revenues that clubs were able to earn through broadcasting rights.

7 UK Parliament (2011), ‘Football Governance – Culture, Media and Sport Committee’, 29 July.

8 Oliver & Ohlbaum Associates (2016), ‘The UEFA Champions League: Time for a new formation’, August.

9 The Ganassa Report (2020), ‘The State of European Football In East Asia’, p. 12.

Download

Contact

Dr Barbara Veronese

PartnerContributors

Related

Download

Related

Blending incremental costing in activity-based costing systems

Allocating cost fairly across different parts of a business is a common requirement for regulatory purposes or to comply with competition law on price-setting. One popular approach to cost allocation, used in many sectors, is activity-based costing (ABC), a method that identifies the causes of cost and allocates accordingly. However,… Read More

The European growth problem and what to do about it

European growth is insufficient to improve lives in the ways that citizens would like. We use the UK as a case study to assess the scale of the growth problem, underlying causes, official responses and what else might be done to improve the situation. We suggest that capital market… Read More