Third country, second thoughts? The EU’s foreign subsidies regulation

The European Parliament and the Council are currently debating the European Commission’s proposed regulation on foreign subsidies, which covers subsidies granted by third countries that have the potential to distort competition in the EU. In particular, the proposed regulation targets large M&A deals and public procurement procedures involving financial contributions from public authorities outside the EU. Economic tools from the state aid context could help to assess the existence of a foreign subsidy, and its impact on competition.

In May 2021, the Commission adopted a proposal for a regulation to address distortions caused by foreign subsidies.1 While the granting of support from EU member states is subject to state aid control, no comparable regime is in place for support granted by non-EU countries to companies that operate in the EU. The proposed regulation would provide the Commission with tools to take action when foreign subsidies cause competitive distortions in the EU market.

The proposed regulation focuses in particular on large mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and public tender procedures, where investors benefitting from subsidies from a non-EU country may be able to make advantageous offers, thereby distorting the level playing field in the EU. An overview of the proposed regulation is provided in the box below.

Overview of the Commission’s proposed regulation

The regulation proposes the introduction of the following tools for the Commission to investigate foreign subsidies:

- a notification-based tool to investigate M&A deals involving a financial contribution by a non-EU government, where the EU turnover of the company to be acquired (or of at least one of the merging parties) is at least €500m and the foreign financial contribution is at least €50m;

- a notification-based tool to investigate bids in public procurements involving a financial contribution by a non-EU government, where the value of the procurement is at least €250m;

- a tool to investigate all other market situations and M&A deals and public procurement procedures on the Commission’s own initiative.

In relation to the two notification-based tools, the acquirer or bidder will have to notify ex ante any financial contribution received from a non-EU government in the previous three years, irrespective of whether the funding confers a benefit on the recipient (which is one of the defining elements of a foreign subsidy, as described below). The Commission would assess whether such contributions confer a benefit on an undertaking that engages in an economic activity in the EU market and therefore amount to a foreign subsidy. The deal in question cannot be completed and the investigated bidder cannot be awarded the contract before the Commission has finalised its review.

If the Commission finds that a foreign subsidy has been granted, it will balance the potential positive effects of the foreign subsidy on the development of the relevant subsidised activity against its negative effects on competition in the EU (in a so-called balancing test). The Commission can impose redressive measures or accept commitments from the companies concerned to limit potential competitive distortions.

Source: European Commission (2021), ‘Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on foreign subsidies distorting the internal market’, COM(2021) 223 final, 5 May.

This article outlines the tools that can be used to assess—from an economics perspective—the existence of a foreign subsidy, and whether the negative effects of a foreign subsidy might outweigh their positive effects.

From ‘financial contribution’ to ‘subsidy’—the definition of a foreign subsidy

According to the proposed regulation, a foreign subsidy exists:2

where a third country provides a financial contribution which confers a benefit to a recipient in the EU and which is limited, in law or in fact, to an individual undertaking or industry or to several undertakings or industries.

Under the proposed regulation, the definition of a financial contribution is relatively broad. It captures different types of measure, such as grants, loans, equity injections, loan guarantees and fiscal incentives, as well as the supply or the purchase of goods and services. As most investors acquiring companies in the EU are private undertakings, certain private firms (including financial institutions) may be captured by the proposed regulation, if they have received a financial contribution from a foreign state in the past.3

For a financial contribution to constitute a subsidy, however, it must ‘confer a benefit to a recipient in the EU’. In order to assess this, two aspects need to be considered:

- whether the financial contribution from the foreign state has conferred an advantage on the investor or acquirer;

- whether this advantage might be ‘passed on’ to a recipient in the EU.

For example, a foreign subsidy received by an investor or acquirer in the past could strengthen its financial position and lead to an inflated bid for a notifiable M&A transaction, such that the benefit is ‘passed on’ to a recipient in the EU.

How to assess whether a financial contribution confers a benefit

The Commission clarifies that the existence of a benefit should be determined based on an assessment of the practice of private investors.4 Under state aid rules, an economic advantage is not conferred (and hence funding does not constitute aid) if the public authority providing the funding does so on market terms. Therefore, it is plausible that the same methods that are available to determine compliance with the so-called market economy operator principle (MEOP) in state aid cases could also be used to assess the existence of a ‘benefit’ in the context of foreign subsidies.5

The MEOP, and the economic conceptual framework underpinning it, has become a key tool used by the Commission to assess a broad spectrum of public measures. In the context of foreign subsidies, a MEOP test could be applied to assess whether a financial contribution from a third country confers a benefit on the investor or acquirer (which could potentially be ‘passed on’), and whether a benefit is conferred on a recipient in the EU as a result of the transaction (e.g. a notifiable M&A transaction). Two stylised examples are provided in the box below.

Stylised examples: assessing the existence of a foreign subsidy

Company A, a privately owned company based in the EU, receives a loan from a state-controlled bank outside of the EU to build a new factory. In addition, Company A plans to acquire a company in the EU. Company A and the target company have a turnover below €500m and thus the acquisition does not need to be notified to the Commission under the proposed regulation. However, the loan and the acquisition can be subject to an investigation.

The acquisition should not be captured by the regulation if the loan for the construction of the new factory was granted on market terms. However, if the loan was granted at reduced interest rates, the amount of the subsidy (i.e. the difference between the amount that Company A pays on the loan and the amount that it would pay on a comparable commercial loan) would need to be determined. If the amount of the subsidy is above €5m (i.e. the minimum threshold that triggers the regulation), it could be assessed whether the company could have financed the acquisition in the absence of the loan from the state, and if the acquisition of the EU company is on market terms, such that the financial benefit derived from the foreign subsidy is not used to artificially increase the offered purchase price of Company A.

Company B, a public company based outside the EU that plans to participate in a merger (or a bidding process) in the EU, and that is also in financial difficulty, has received an equity injection from its shareholder for restructuring purposes. Unless an assessment was made prior to the recapitalisation as to whether it would be more advantageous for the shareholder to liquidate the company or to proceed with the restructuring, it is possible that the financial contribution will constitute a foreign subsidy.

Source: Oxera.

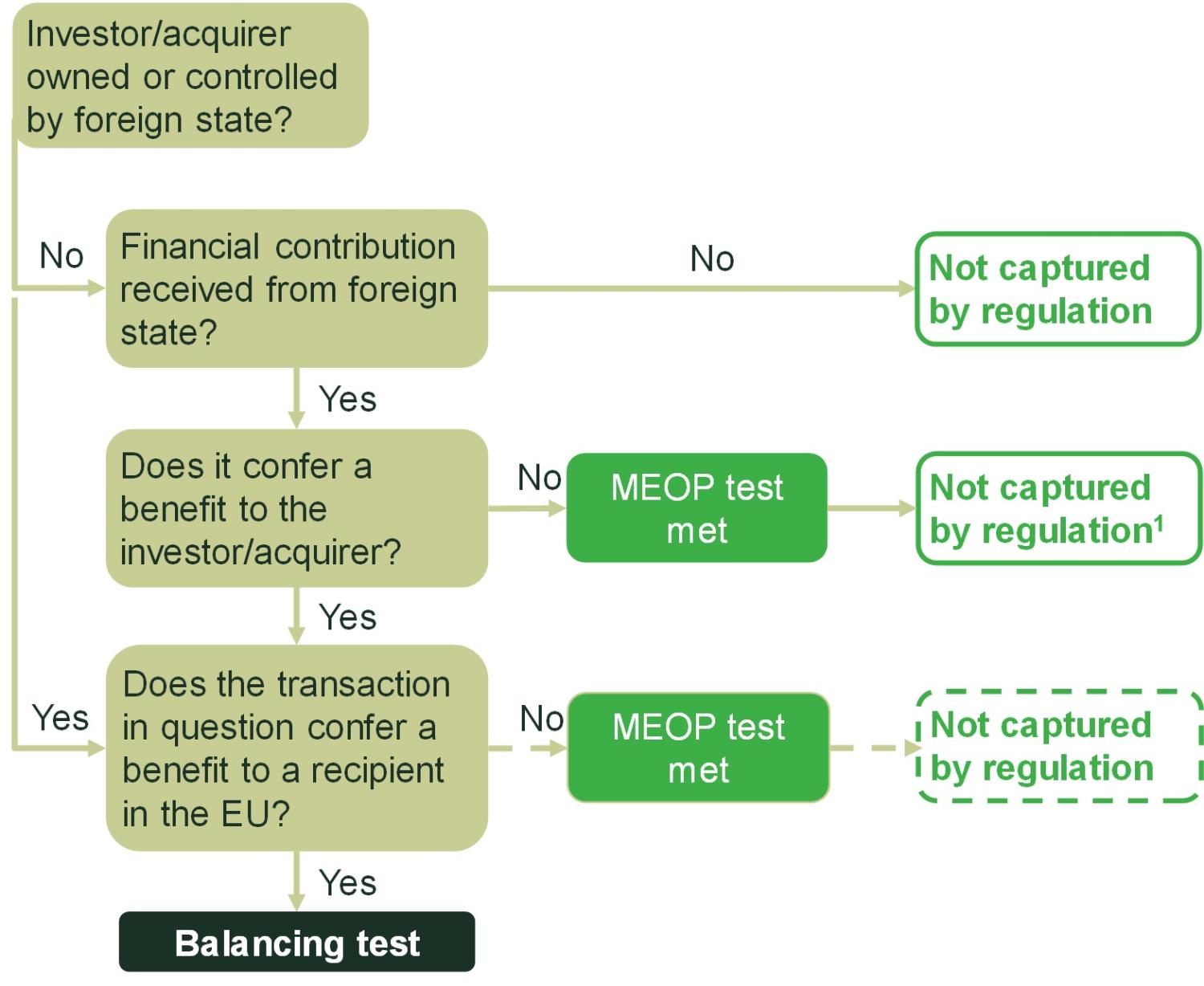

The figure below summarises the process for assessing the existence of a foreign subsidy, and at which points a MEOP assessment could be undertaken to determine whether the transaction would be likely to be captured by the proposed regulation.

Figure 1 Assessing whether the transaction in question would be captured by the regulation

Source: Oxera.

While a MEOP assessment could be undertaken to assess whether a financial contribution from a foreign state confers an advantage on an investor or acquirer, under the Commission’s current proposal, it is unclear if a MEOP test in relation to the transaction in question would be sufficient to rule out that the investor or acquirer is captured by the regulation, in case it has received funding not on market terms from a non-EU state over the last three years. It remains to be seen how the Commission will apply the assessment in practice.6

In order to assess whether a public measure is in line with the MEOP, benchmarking and profitability analysis can be undertaken.

- Benchmarking involves analysing whether the terms (especially the price) of a transaction are in line with comparable transactions observed on the market between private entities.

- Profitability analysis can be used to assess whether the expected return from the transaction is in line with, or higher than, the return required by a private operator in a similar transaction.

In addition to financial data provided by the company under assessment, the MEOP assessment can be based on data from financial databases such as Datastream, Orbis or Bloomberg, as well as analyst reports. Examples of the types of economic and financial analysis that could be applied to assess the existence of a foreign subsidy are set out in the box below.

Economic and financial analysis for assessing whether a financial contribution confers a benefit

1. Debt financing in the form of loans

The pricing of a loan (i.e. its interest rate) depends on a number of factors, including: the business and financial risks of the borrower (as measured by its credit rating); the collateral underpinning the loan; the amount, duration and seniority of the loan; and the repayment schedule.

There are two approaches to estimating the market-conforming interest rate on loans. The most straightforward way is to benchmark the interest rate on the loan to any existing and sufficiently comparable commercial loans of the company concerned, if available. Alternatively, the interest rate on the loan in question can be benchmarked against the rate on comparable loans/bonds of companies with a similar credit rating. This analysis could be based on the interest rate on loans or bond yields of traded companies with similar credit ratings, preferably within the same sector. To further develop the evidence that the loan is granted on market terms, one can assess whether the loan covenants correspond to those that are typically required by private creditors, and whether the borrower is expected to be able to generate sufficient cashflows to meet the interest payments and repay the loan principal.

2. Purchase of goods and services

In the state aid context, the Commission typically assumes that a public contract is priced on market terms if it is awarded through a competitive tender. If a contract is not awarded through a tender, benchmarking and/or profitability analysis can be applied to determine the market price of the transaction. If data on comparable transactions is available (e.g. similar services/goods purchased by public authorities through a tender in the past), the price of the goods and services in question could be benchmarked directly. Source: Oxera.

A MEOP assessment under the foreign subsidy regulation might be more challenging than under state aid rules, in particular when it comes to asset valuation in the context of M&A deals. If a foreign company outbids EU competitors, this might be because its valuation of the target is significantly higher than other bidders, as opposed to increased willingness to pay due to foreign subsidies. However, this raises a question about how inflated bids driven by subsidised funding can be separated from genuine high valuations. This highlights that particular attention should be paid to the evidence underpinning foreign investors’ valuation analysis. For example, if strategic considerations (e.g. expected synergies) are a key driver for a valuation, the commercial benefit of such synergies should be quantified to the greatest extent possible.

Source: Oxera.

How to undertake the balancing test

When a foreign subsidy has been identified, the Commission will balance the negative effects of the foreign subsidy on competition in the EU with its positive effects on the development of the relevant subsidised activity.7 If the negative effects outweigh the positive effects, the Commission can impose remedies, including requirements on the company to reduce its capacity or market presence, restrictions on certain investments, or the divestment of certain assets.8 In some cases, the Commission can require the foreign subsidy to be repaid, including with interest.9

In its proposed regulation, the Commission outlines a set of indicators to determine the distortive impact of a subsidy on competition, including:10

- the amount and nature of the subsidy;

- the purpose and conditions attached to the subsidy;

- the situation of the undertaking and the markets concerned, such as the degree of barriers to entry;

- the level of economic activity of the undertaking concerned on the EU market, and its presence on the internal market.

As outlined in Oxera’s study for the Commission that analysed the impact of aid on competition, similar economic techniques to those that are standard in merger control could be undertaken to assess the impact of a foreign subsidy on competition.11 In particular, the following steps could be undertaken:

- identifying the main characteristics of the foreign subsidy (such as the form of the subsidy, or the amount of subsidy granted) and defining the relevant markets in the EU that might have been affected by the foreign subsidy;

- defining the hypotheses to be tested to assess the impact of the foreign subsidy on the relevant EU markets relative to what would have been likely to have been the case in the absence of the foreign subsidy (i.e. the counterfactual scenario);

- assessing and measuring the impact of the foreign subsidy on competition in the EU relative to the counterfactual scenario.12

In relation to the positive effects of a subsidy, the proposed regulation does not discuss how the impact of a subsidy on the development of the relevant economic activity in the EU will be assessed. Under state aid rules, the balancing exercise involves assessing the impact of the aid on a common interest objective, such as the impact of the aid on employment and GDP, research spillovers or regional connectivity, depending on the market failure that is addressed. Similar to a state aid assessment, it therefore seems important that, as a foreign investor, a transaction is also considered in the context of the EU’s economic policy objectives in order to meet the balancing test. However, the way in which the balancing exercise will be undertaken by the Commission remains to be seen.

Looking ahead

The proposed regulation is far reaching, and will bring about significant changes for foreign investors who are considering investing or expanding their activities in the EU. For firms looking to make acquisitions that would be captured by the new rules, the proposal introduces the need to undertake detailed due diligence of the bidder and the target. In this article, we have outlined some methods to guide the analysis.

In the state aid context, the concept of the MEOP (and the economic conceptual framework underpinning it) has been developed and refined over the years. It has become a key tool for the Commission to assess the existence of aid for a broad (and increasingly complex) spectrum of public measures. As the Commission is well acquainted with the economic methods used to assess the MEOP, it is plausible that public funding from third countries will not be considered to be a foreign subsidy, and thus will fall outside the scope of regulation, if it meets the requirements of the MEOP.

Even if a financial contribution is considered to constitute a subsidy, economic analysis, as used in state aid compatibility assessments, could be applied to assess the degree of distortion to competition in the EU resulting from a foreign subsidy, as well as the subsidy’s positive effects.

How the Commission will apply the regulation in practice remains to be seen, particularly with regard to the balancing test. But as we have set out in this article, economic and financial analysis, alongside the necessary legal analysis, can help investors to navigate the complex requirements of this regulation.

1 European Commission (2021), ‘Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on foreign subsidies distorting the internal market’, COM(2021) 223 final, 5 May.

2 European Commission (2021), op. cit., Article 2. Foreign subsidies below €5m are not subject to the regulation.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid., p. 16, para. (10).

5 For further information on the methods available to establish MEOP compliance in state aid cases, see Robins, N. and Puglisi, L. (2020), ‘The market economy operator principle: an economic role model for assessing economic advantage’, in L. Hancher and J.J. Piernas López (eds), Research Handbook on European State Aid Law, Second Edition, Edward Elgar.

6 In any event, a MEOP assessment on the transaction in question could provide helpful evidence as to whether competition in the EU is more likely to be distorted (as part of the balancing test), in particular for cases that have to be notified to the Commission.

7 European Commission (2021), op. cit., Article 5.

8 Ibid., Article 6.

9 Ibid., Article 6(3)(h).

10 Ibid., Article 3. Certain categories of subsidy are deemed ‘most likely to distort the internal market’. These include public support to ailing undertakings (unless a credible restructuring plan exists), unlimited guarantees, and subsidies that are directly aimed at supporting a concentration or a participation to a tender. Ibid., Article 4.

11 See Oxera (2017), ‘Ex post assessment of the impact of state aid on competition’, Final report, prepared for the European Commission Directorate-General for Competition, November.

12 For further details about the economic tools that can be used to assess the impact of aid on competition, see Oxera (2017), op. cit.

Related

The European growth problem and what to do about it

European growth is insufficient to improve lives in the ways that citizens would like. We use the UK as a case study to assess the scale of the growth problem, underlying causes, official responses and what else might be done to improve the situation. We suggest that capital market… Read More

The 2023 annual law on the market and competition: new developments for motorway concessions in Italy

With the 2023 annual law on the market and competition (Legge annuale per il mercato e la concorrenza 2023), the Italian government introduced several innovations across various sectors, including motorway concessions. Specifically, as regards the latter, the provisions reflect the objectives of greater transparency and competition when awarding motorway concessions,… Read More