Ticking the boxes on a green self-assessment, and the risk of greenwashing

In EU competition law, the key criteria for green self-assessments for companies are ‘fair share’ and ‘indispensability’. But how can we assess these from an economics perspective? And how can we distinguish legitimate sustainability agreements from greenwashing? We consider how the European Commission deals with consumer benefits in its Draft Horizontal Guidelines on sustainability, taking into account recent guidance on this topic from the Dutch competition authority.

In the EU, the first sustainability agreements are being tested in front of national competition authorities (NCAs) in the context of the European Commission’s Draft Horizontal Guidelines.1 The parties to these agreements often undertake a self-assessment under Article 101(3) TFEU and request guidance from the authority. We offer an economics perspective on two key criteria for these self-assessments—fair share and indispensability—and seek to provide some much-needed clarity on how to distinguish legitimate sustainability agreements from greenwashing.

Saving the planet or greenwashing?

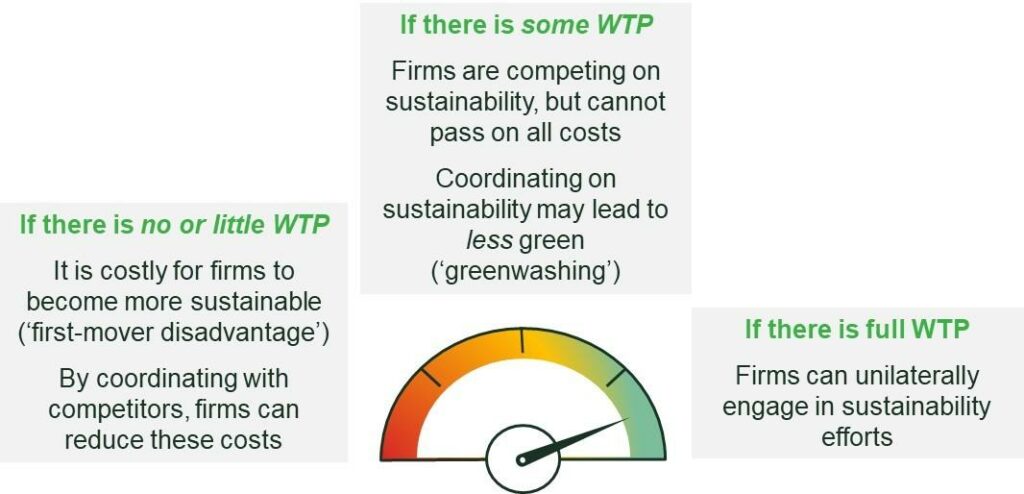

Consumer willingness to pay (or a lack of it) plays a crucial role in the economic rationale behind many sustainability agreements. This is because this willingness to pay is linked to the presence or absence of a ‘first-mover disadvantage’. If there is demand for greener products and sufficient willingness to pay, a firm can unilaterally engage in greener production—as any higher costs can be passed on to consumers (see the right-hand side of Figure 1 below). An individual firm is thus not ‘penalised’ for being the first to invest in this greener production while its competitors continue to supply the old product (the ‘grey product’). In fact, it can benefit from being the first mover, as this green feature of the product then becomes a parameter over which companies compete—and there is no longer a first-mover disadvantage. In such cases, as discussed below, it is usually assumed that there is no need for competitors to coordinate, unless cooperation is ‘indispensable’ (for example, because of a need for significant investment or risk).

In some cases, however, firms may indeed face a first-mover disadvantage in producing a greener product. This is the case where competitors are able to steal market share if consumers do not value the green product (enough) and are not willing to pay the (often) higher price. Cooperation could help to overcome this issue (see the middle section of Figure 1).

Figure 1 Three levels of willingness to pay

Source: Oxera.

Research by Schinkel and Spiegel (2017) has shown that under certain assumptions, when costs are not particularly high and consumers have at least some willingness to pay for green products, coordination will lead to lower levels of sustainability than when companies act unilaterally.2 This is referred to as ‘greenwashing’. In the authors’ model, sustainability is modelled as a parameter of quality. Hence, when firms coordinate, they can all choose a lower level of ‘green’ and ‘quality’, as this tends to be cheaper, without losing consumers to others. Under competition, firms can win consumers by investing more in green and quality—but this comes at a cost.

If there is no or little willingness to pay, there is (also) a first-mover disadvantage. To get around the first-mover disadvantage, firms can coordinate and jointly introduce a new greener product to the market (see the left-hand side of Figure 1). This might also lower the costs for an individual firm. However, given that there is no or little willingness to pay, such agreements may be viewed with suspicion as the commercial rationale for the firms involved is not obvious.

It may therefore be difficult for NCAs to distinguish between situations where there is a genuine rationale for sustainability coordination to deliver good outcomes for firms and society, and cases where firms take advantage of the ability to coordinate to deliver good outcomes for themselves and poor outcomes for society. So how should a NCA attempt this distinction? And, in answering this question, how should firms that are seeking to coordinate for the benefit of the environment present their case to the NCA?

First, it is important to consider the economic rationale for coordination that is due to spillover effects (externalities) among the coordinating firms. When this rationale is factored in, cooperation on green goals can make more economic sense. Because of spillovers, the level of sustainability efforts by other firms actually has a positive effect on a firm achieving its own objectives.

Consider the following example. When an entire industry suffers from a poor reputation due to the environmental damage caused by its collective behaviour, any one firm may face insufficient incentives to improve the industry’s image by investing a significant amount in sustainability. However, coordinating on improving sustainability could help to improve the overall reputation of the industry, which in turn would benefit all the firms involved by (for example) increasing consumer demand.3 Hence, allowing firms to coordinate their sustainability efforts would lead to higher levels of overall effort. This agreement, while falling in the left-most box in the figure, can be considered as rational.

Second, an NCA (or individual companies as part of a self-assessment) could test whether the agreement actually increases the level of sustainability towards a socially optimal level,4 or whether it instead leads to a lower level of sustainability. Hence, if the NCA sees a risk at this point, it could test all agreements case by case.

The Dutch Chicken of tomorrow case provides a good example. Although it concerns animal welfare rather than greener production, the same approach can be used as for assessing sustainability agreements. In 2015, the Dutch competition authority (ACM) assessed whether an agreement among Dutch supermarkets to ban sales of the least animal-friendly chicken would meet all the criteria of Article 101(3) TFEU and would therefore be exempted under competition law. The authority concluded that it did not, as the willingness to pay for the ‘chicken of tomorrow’ did not outweigh the price increase.

Interestingly, in a survey, the ACM also asked consumers about their willingness to pay for two categories of even ‘better’ chicken (where the birds were housed in larger cages, for example). This showed that willingness to pay was €6.99 and €7.90 per kg for each of these categories. It is likely that this willingness to pay would outweigh the higher costs and prices of the better product,5 and as such more ambitious welfare standards by supermarkets might have been exempted.6

Benefits for ‘fair share’ under the Draft Horizontal Guidelines

As discussed above and in our previous Agenda article,7 by capturing spillovers between firms a sustainability-enhancing cooperation agreement could be economically rational, even if it is not rational for a firm to pursue it on its own. We are pleased to see that the Commission recognises the importance of capturing spillovers in its recently updated Draft Horizontal Guidelines.8

In the Draft Horizontal Guidelines, the Commission now recognises three types of benefit to consumers that could follow from sustainability agreements: (i) individual use value benefits; (ii) individual non-use value benefits; and (iii) collective benefits.9

We consider that this is the most significant shift relative to the current version of the Horizonal Guidelines, in which only the first category above was considered. Compared with the existing version, a sustainability agreement therefore has a higher chance of generating sufficient benefits for consumers, which would be weighed against any potential negative effects of the agreement on competition. We welcome the introduction of these further categories.

Taking a step back, the newly introduced categories comprise one of the four criteria that need to be met under Article 101(3) TFEU for the agreement to be exempted from the cartel prohibition under Article 101(1). The benefits can be quantified to test whether the ‘fair-share criterium’ is met. This means that consumers must receive a fair share of the resulting benefits—i.e. the efficiency gains that the agreement generates.

As set out below, two of the three categories of benefit involve spillovers. However, the Commission looks at spillovers among consumers as opposed to the spillovers among firms discussed above. The first category—individual use value benefits—involves no spillovers among consumers, as the use value to a consumer is independent of whether others are consuming the product. However, the other two categories10 do provide room for spillover effects to be incorporated into the analysis; the use value benefits and the individual non-use value benefits can be quantified using a consumer survey that tests willingness to pay. The question is then which type of willingness to pay to use.

Inderst and Thomas (2021) suggested that, instead of looking at ‘regular’ willingness to pay, we should look at ‘reflective’ willingness to pay. This represents the monetary amount that a consumer is willing to pay for a product based on additional information provided to them and additional time for deliberation.11 Often, in the case of sustainability agreements, the reflective willingness to pay is higher than the ‘regular’ willingness to pay. It is unclear which form the Commission would accept.

While the Draft Horizontal Guidelines explicitly bring in consumer spillovers and internalise negative externalities and sustainability benefits for a larger segment of society (under collective benefits, category 3), they do restrict the number of situations in which the spillover benefits can be taken into account.12 Consumers of the products or services affected by the agreement must substantially overlap with the beneficiaries in order for the benefits for the beneficiaries to be included in the balancing exercise of Art. 101(3) TFEU.13 It is unclear under what conditions this threshold of substantial overlap will be met.

Indispensability

Indispensability is another of the cumulative criteria of Article 101(3) TFEU. In short, this means that the criteria of Article 101(3) are met only if the restrictions that are caused by the agreement are needed (indispensable) in order to achieve the efficiency gains generated by the green agreement.14 The first-mover disadvantage may be what makes an agreement indispensable. The Commission acknowledges this.15 Similarly, the presence of high risk and high investment can prevent companies from pursuing sustainability goals unilaterally. In such circumstances, cooperation could reduce those hurdles, in which case the agreement would be considered indispensable.

Here we highlight one example of the latter type of coordination. The ACM has recently published an informal opinion on the proposed collaboration between energy companies Shell and TotalEnergies on the storage of CO2 in empty North Sea gas fields (Project Aramis).16 In this case, both the risk and level of investment played a role in determining that the agreement was indispensable.17

Among other aspects, the project involves supplying a trunkline with a planned capacity of 22 megatons per annum (MTPA) to transport the CO2 and store it in depleted gas fields.18 The agreement for which guidance was sought focuses on the first phase for 5 MPTA, and would unlock Project Aramis as a whole, including its subsequent competitive phase (the remaining 17 MTPA). The initial 5 MTPA is based on the required return on investment as well as the capacity available in the depleted gas fields from the parties.19

The required investments would be too high for the companies to take on unilaterally,20 and this would lead to duplication of infrastructure (the pipeline and other network aspects). By teaming up, the parties are able to service the larger combined market through multimodal infrastructure (for both gaseous and cryogenic CO2), instead of each of them focusing on one form of CO2. Given the novel nature of the technology involved,21 this has significant financial risks. By coordinating their plans, the parties create redundancy in the system that reduces these risks in the case of CO2 leakage, for instance.

Based on its assessment of the information provided by the parties, the ACM considered that it is likely that the restrictions involved in the agreement are indispensable.

The ACM further acknowledges the efficiency gains from the project that result from ‘costs savings by avoiding infrastructure duplication, offering economies of scale and scope and reducing risk while creating an innovative market for CCS services in the Netherlands’.22

As part of the self-assessment, the ACM considered the fair share criterion and decided that, in this case, a quantitative analysis of cost versus benefits was not applicable. The authority did consider that, ‘based on a rough estimate, the sustainability benefits clearly outweigh the costs’.23

Overall, across the various criteria of article 101(3) TFEU, the ACM considered that Shell and TotalEnergies should be allowed ‘to restrict their mutual competition when selling the first 20% of the transport and storage of CO2 in their empty gas fields’.

The link between fair share and indispensability

In the case of low or zero willingness to pay for green products and services, firms acting unilaterally often face a first-mover disadvantage. This may be a reason for an agreement to be considered indispensable in achieving environmental benefits.24

However, firms also need to be able to show that the other elements of Article 101(3) are met, such as ensuring that a fair share of the benefits are passed on. Focusing purely on the private willingness to pay of consumers may not meet this hurdle in cases where individual willingness to pay is low but wider benefits to society are high.

A more fruitful approach involves estimating the benefits to those who are beneficiaries of the environmental benefits but are not consumers of the products or services that are subject to the agreement. This approach to assessing the benefits is supported by the draft Commission guidance on horizontal agreements, but it remains to be seen how the draft text will be adopted in the final version.

1 European Commission (2022), ‘Draft Horizontal Guidelines’ (accessed 25 August 2022). For example, see two recent cases by the Netherlands ACM (Authority for Consumers & Markets (2022a), ‘ACM favors collaborations between businesses promoting sustainability in the energy sector’, news, 28 February) and the German Bundeskartellamt (Bundeskartellamt (2022), ‘Achieving sustainability in a competitive environment – Bundeskartellamt concludes examination of sector initiatives’, news, 18 January).

2 Schinkel, M.P. and Spiegel, Y. (2017), ‘Can collusion promote sustainable consumption and production?’, International Journal of Industrial Organization, 53, pp. 371–98.

3 For some examples, see Oxera (2021), ‘When to give the green light to green agreements’, Agenda, September.

4 This level can be defined as the sustainability level that matches the consumer preference for sustainability, proxied by the sustainability level for which there is sufficient willingness to pay.

5 The ACM did not report the increased costs that poultry farmers would have needed to impose in order to provide these better chickens, so we cannot make the same balance calculation. However, it is not unrealistic to assume that the balance of effects would have been positive for the better chicken.

6 In this case, one might question whether this means that there is enough willingness to pay to do this unilaterally, and whether this means the agreement was not needed to begin with.

7 Oxera (2021), ‘When to give the green light to green agreements’, Agenda, September.

8 This section of the article is based on Oxera’s submission to the European Commission’s consultation on the Draft Horizontal Guidelines, which provide guidance on how to interpret and apply the Horizontal Block Exemption Regulations on Research & Development and Specialisation agreements and how to self-assess compliance with Article 101(1) and Article 101(3) TFEU. The European Commission updates the Horizontal guidelines every decade, and the most recent updated version was published in 2011. Prior to publication, there is a consultation period during which stakeholders can comment on the Draft guidelines. Spillovers are mentioned in the Draft Horizontal Guidelines at para. 545.

9 European Commission (2022), para. 590 for individual use value benefits; para. 594 for individual non-use value benefits; and paras 601 and 606 for collective benefits.

10 Individual non-use value benefits: indirect benefits resulting from consumer appreciation of the impact of their sustainable consumption on others. Collective benefits on different markets: e.g. positive externalities that benefit everyone, if consumers who ‘pay’ for the benefit substantially overlap with customers who benefit, as in the case of climate change abatement.

11 Inderst, R. and Thomas, S. (2021), ‘The Scope and Limitations of Incorporating Externalities in Competition Analysis within a Consumer Welfare Approach’, December.

12 European Commission (2022), op. cit., para. 601.

13 European Commission (2022), op. cit., para. 606.

14 The full text of article 101 TFEU states that paragraph 1 can be declared inapplicable if (among other factors) the agreement does not ‘impose on the undertakings concerned restrictions which are not indispensable to the attainment of these objectives’ (article 101(3) TFEU).

15 European Commission (2022), para. 584.

16 Authority for Consumers & Markets (2022b), ‘ACM: Shell and TotalEnergies can collaborate in the storage of CO2 in empty North Sea gas fields’, news, 27 June.

17 Oxera has been supporting the parties on this matter. All information on the case that is provided here is based on public sources.

18 Authority for Consumers & Markets (2022c), ‘No action letter for the Agreement between Shell and TotalEnergies regarding a joint marketing initiative for CCS services (project Aramis)’, 27 June.

19 ‘Neither of the Parties is currently independently able to reach 5 MTPA of storage capacity by relying on additional fields, without adding considerable costs and/or within the required time frame, as the other fields owned by the Parties are either: (i) too far away, (ii) still in gas production, or (iii) more complex to use so the operation would be more costly.’ (Authority for Consumers & Markets, 2022c, op. cit.)

20 ‘The Parties argue that the investments and risks associated with Project Aramis are significant. The investment of several billion Euros in Project Aramis, including the planned high-capacity trunkline’ (Authority for Consumers & Markets, 2022c, op. cit.)

21 The project involves ‘deploying integrated technology for processing gaseous and cryogenic CO2 for the first time’ (Authority for Consumers & Markets, 2022c, op. cit.)

22 Authority for Consumers & Markets (2022c), op. cit.

23 Authority for Consumers & Markets (2022c), op. cit.

24 European Commission (2022), ‘Draft Horizontal Guidelines’, para. 584.

Related

Future of rail: how to shape a resilient and responsive Great British Railways

Great Britain’s railway is at a critical juncture, facing unprecedented pressures arising from changing travel patterns, ageing infrastructure, and ongoing financial strain. These challenges, exacerbated by the impacts of the pandemic and the imperative to achieve net zero, underscore the need for comprehensive and forward-looking reform. The UK government has proposed… Read More

Investing in distribution: ED3 and beyond

In the first quarter of this year the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC)1 published its vision for the UK’s electricity distribution network. Below, we review this in the context of Ofgem’s consultation on RIIO-ED32 and its published responses. One of the policy priorities is to ensure… Read More