Time to choose: retail market opening in the water sector

One of the biggest shake-ups in the English water sector will take place on 1 April 2017, when non-domestic customers—including businesses and public sector organisations—will be able to choose their retail supplier. But is the sector prepared? Will market opening be a ‘big bang’ or a slow-burner? And will companies play by the rules?

The water industry in England is about to embark on the next stage of its development. Unlike the GB electricity and gas sectors, the water industry has remained vertically integrated since it was privatised in the late 1980s. This has meant that, in most instances, within each company supply area, the same company has provided the entire service from source to tap (and the reverse on the wastewater side).

However, on 1 April 2017 this will come to an end for eligible non-domestic customers. From this date, most businesses, charities and public sector organisations will be able to decide who provides them with retail services—including billing, meter reading, tailored customer services, and water efficiency advice. This follows an identical reform introduced in the Scottish water industry in April 2008, and will result in a cross-border Anglo-Scottish retail sector.1

Is England ready?

So, will the market open without hitches? A lot of planning has gone into the process. Over the past three years, Open Water—a programme group comprising government, water companies and regulators—has put in place the necessary arrangements to prepare for the new retail market. This has included developing:

- the Market Arrangements Code (MAC)—which sets out the new processes in relation to the ‘Market Operator’ (the central organisation responsible for enabling switching and calculating the charges owed to each wholesaler);2

- the Wholesale Retail Code (WRC)—which sets out the relationship between wholesalers and retailers and how the market will operate.3

The WRC in particular is a key document in ensuring a level playing field for new entrants (for example, it puts in place processes to ensure that wholesalers do not give their own retail business preferential treatment in response to operational issues). Water companies have been making the necessary changes to their wholesale business processes in order to make sure that they will comply with the requirements of the WRC upon market opening.

The companies have provided assurance that they are ready, leading the Environment Secretary to confirm that the necessary arrangements are in place for the retail market to open as planned on 1 April 2017.4

The emerging landscape

The incumbent water companies have also been selecting their strategies in preparation for market opening. Through the Water Act 2014, water companies can apply to the Secretary of State for the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra) to exit the non-household retail market if they want to5—something that the Water Industry Commission for Scotland (WICS), Ofwat (the economic regulator of the water industry in England and Wales) and Oxera have argued in the past is important for effective market functioning.6

Exit serves a number of purposes. It can be a means through which the functions of a retailer can be legally separated from the wholesale business. Exit also enables retailers to leave the market altogether, to be acquired by other retailers taking a more proactive interest. Furthermore, exit can facilitate mergers between retailers, leading to potential scale economies.

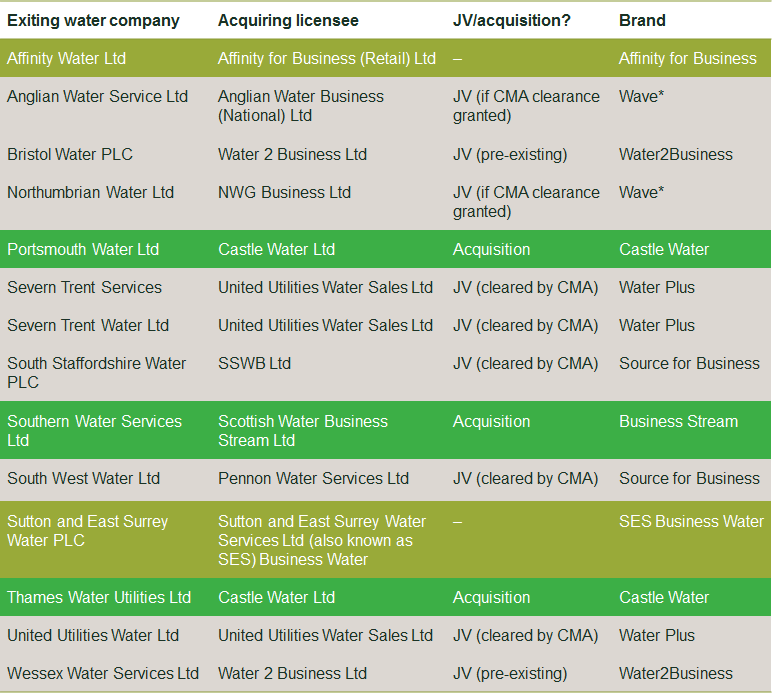

As shown in Table 1, 14 applications to exit the non-household retail market have been granted by the Secretary of State to date.

Table 1 Undertakers allowed to exit

Source: Based on Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (2017), ‘Decision: companies with approval to withdraw from the non-household retail market for water’, 14 February. Also based on information from the Open Water website and from the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) and various water company websites.

Three of these have involved a ‘hard exit’ (Portsmouth, Southern and Thames). Here, the non-domestic retail business has been acquired by a third-party buyer active in the Scottish retail market. Exit has also been used as a way to facilitate mergers among retail businesses, with nine cases involving a JV with another water company.7 The remaining two exits have involved the transfer of the non-domestic retail business to a new entity that nonetheless remains under the same ownership.

The JV/merger route has attracted the attention of the CMA. The largest transaction by far has been the Severn Trent and United Utilities JV, Water Plus, which received clearance in May 2016.8 The most recent case to receive clearance is the JV between South Staffordshire Water and South West Water, Source for Business, which was cleared on 10 March 2017.9 The Anglian/Northumbrian JV, Wave, was also announced in early 2017, and will only be taken forward upon CMA clearance. In the meantime, NWG Business and Anglian Water Business will enter the market as separate entities.10

To date, mergers or JVs do not appear to have been contested by the CMA. This may be due to the fact that at market opening there will still be several retailers in the non-household retail market, meaning that the concentration of the merged entity or JV does not pose competition concerns. In addition—and as discussed below—entry is occurring from outside the England water sector. It will be interesting to see how the CMA’s thinking develops in future, if a number of subsequent mergers do occur. The CMA has not set out at what point a merger would result in a significant lessening of competition, or what it considers is the minimum number of competitors required in the sector.

These examples of consolidation show that the water industry is undergoing strategic change—a point noted by the Ofwat Chairman, Jonson Cox, in a water industry conference in March 2017:11

Over the last year events have moved at a pace. Two big companies have divested their retail business; two others have formed a joint venture so as to minimise costs and get the benefits of volume that are required in a low margin business. Others are rumoured to be selling their businesses, [water-only companies] are collaborating or outsourcing. It shows that if the incentives and opportunities are there, the sector does respond and we see a plurality of solutions.

There is also new entry in the sector. Scottish companies, Castle Water and Business Stream, have acquired the customer bases of English retail businesses, which provides them with a springboard in England ahead of market opening (see Table 1). Other Scotland-based companies have also obtained retail licences to operate in England, including Clear Business Water, Cobalt Water, Everflow, and Veolia Water. These companies will, however, be competing for custom without an existing customer base in England. In addition, some England-based retailers will benefit from their own experience of operating in the Scottish market. These include Three Sixty Water Services (owned by Yorkshire Water), Water Plus, and Water2Business.

There are also completely new niche players in England, including Regent Water (a gas supplier), The Water Retail Company, Waterscan, and Advanced Demand Side Management Limited—each with its own business model. Peel Water, which currently supplies new-build developments through the inset appointment process, is the most recent retailer to have obtained licence approval.12

Developing a strategy

A vast array of strategies and business models are therefore being pursued as companies gear up for 1 April. The question is then how the companies will seek to be competitive in the marketplace, and by how much they can reduce their prices to be competitive while still earning a sufficient margin. In this respect, the backstop or default tariffs set by Ofwat provide a net retail margin of 2.5%.13 A number of players have argued that this is too low to promote competition and entry—a point on which Ofwat disagrees.14 Certainly, as discussed above, there is a lot of interest in the market from the supplier side. Time will tell what margins are required to support a healthy market.

In any event, competing on price alone may not be the best strategy for earning a margin. Given the nature of entry, it is more likely that companies will seek to offer value-added services tailored to their customers, such as better water efficiency. Over time, companies may also bundle water retail services with other utilities (including energy). In economic terms, this strategy fulfils two objectives: first, providing additional services means earning an additional margin; and second, by differentiating, companies can avoid the margin-erosion that would occur through aggressive competition on price alone.

Nonetheless, some players may use low-price offerings as a way of securing an initial customer base, and others may pursue low pricing as a longer-term strategy by significantly reducing their cost base through scale economies and/or efficiencies.

Customers may also develop their own strategies. Large multi-site customers—such as supermarkets and public bodies—will find it advantageous to deal with one supplier rather than multiple suppliers, and may seek to negotiate the terms of any water efficiency offerings. One large customer has gone a step further: Greene King—a brewery with an estate of over 1,750 pubs and other premises in England—has obtained a self-supply licence. Technically, this means that it will deal directly with the wholesalers. In practice, it has signed a contractual agreement with Waterscan, which will provide the retail functions (including meter reading, wholesaler management, settlement, and certain water efficiency services).15 Indeed, Waterscan’s business model is based around Water Procurement and Self-Supply.16 Other (very) large non-household customers may adopt similar arrangements as they consider their options.

Protecting consumers

A point on which there has been much debate is the role of third-party intermediaries (TPIs)—or brokers—in the water market. These are common in the energy market and in financial services, and have established a presence in the Scottish water market. TPIs are likely to have an extensive role in the liberalised water market in England.17 At one end of the market, they will include price comparison and switching sites. At the other end, brokers are likely to provide ongoing services for customers once they have switched, such as in validating and auditing bills, advising on water efficiency, and re-negotiating and searching for deals.

While Ofwat notes that TPIs have a positive role to play in the functioning of the market, the regulator also has concerns—especially in relation to protecting smaller business customers, who may be targeted by unscrupulous brokers. First, Ofwat does not have powers to regulate TPIs in the same way that it regulates licensees. Instead, TPIs are subject to general consumer protection law, which prohibits misleading advertising and sales activities.18 Second, experience shows that some TPIs have engaged in poor behaviour elsewhere, especially in energy. While Ofgem (the energy regulator for Great Britain) now has additional powers to enforce consumer protection law, at present Ofwat does not have such formal powers—although it would like them.19

Part of the buck stops with retailers. Licensed retailers in the water sector are subject to a customer protection code of practice (CPCoP), and they must ensure that any TPI they deal with is aware of this and that it is reflected in any business dealings. However, this by itself is likely to be insufficient. Ofwat’s recommendation is that TPIs should be subject to a voluntary code of conduct that builds on the CPCoP principles and the lessons learned from energy.20 Whether this will be enough will become apparent over the coming months.

There are reasons to be wary of mis-selling by intermediaries or even by rogue retailers. Intermediaries may offer complicated contractual services that confuse customers into paying shrouded commissions for add-on services that they do not want or need. From a behavioural economics perspective, in broad terms we might consider the existence of ‘sophisticated’ versus unsophisticated or ‘naive’ consumers. Here, naivety does not refer to lack of intelligence. It’s simply a term used to denote consumers who suffer from behavioural biases—such as inattention to the fine print or procrastination.

Large multi-site customers—such as supermarkets—are likely to fall into the former category. They have the resources to assess the best deals and to buy only those add-on services that meet their needs, while having the profit motivation to push for a good deal (thereby actually acting on their assessment). These customers are likely to benefit from keen pricing, since they are both large and sophisticated purchasers, and suppliers will probably target them with the best deals.

In contrast, small businesses—such as corner shops—may fall into the naive category. They may be persuaded to buy via a cold call. Faced with a particular offering, they may focus unduly on the core price, paying insufficient attention to the need for an add-on product or its price. They may therefore be more prone to excessive brokerage fees, or inappropriate add-on products (such as water efficiency audits that might be useful for other customers but are not in line with their own needs). A smaller customer is also potentially more likely to be sold a deal at the point of contact, as opposed to actively seeking a deal in the first instance.

The key danger for market functioning is that it could be difficult for a company to make a sufficient margin from smaller, naive customers without selling add-on services (see also the discussion of strategy above). Economic theory shows that, where there is shrouding of add-on products and enough naive consumers in the market, the process of competition does not deter consumer exploitation. In such circumstances, all firms engage in exploitative behaviour, in which sophisticated customers benefit from good deals on the core product, and the profits are made from those who (naively) buy the add-ons. Firms do not have an incentive to educate customers in this situation.21

This is not just a theoretical possibility. Mis-selling of payment protection insurance (PPI) to household loan customers has been well publicised.22 Such practices have not been confined to households. In 2016, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) found that nine large banks providing loans to small businesses mis-sold add-on interest rate hedging products (IRHP). The FCA regarded these investors as ‘unsophisticated’, and considered that IRHPs were too complex to be understood by these customers.23

An important issue in water is customer awareness. An Ofwat-commissioned study from January 2017 showed that 70% of businesses were unaware of water market opening.24 And while 79% of large organisations were aware, only 28% of micro-organisations were aware of the coming changes (or around 40% in the case of small and medium-sized customers). This means that larger customers may be more proactively engaged in assessing the array of available deals than smaller customers. In turn, this increases the risk of mis-selling, as suppliers push their offerings to the latter.

Such behaviour is well documented in the domestic energy sector, where a number of suppliers have been forced to make redress payments for past mis-selling.25 Ofwat has similarly stated that retailers operating in the non-domestic water market that break their licence conditions through not complying with the CPCoP could face fines or risk having their licence taken away.26

Protecting competition

Promoting and protecting the competitive process is also important, and market participants will need to comply with the sector-specific level playing field requirements enshrined in the various codes (discussed above). Importantly, they will need to comply with competition law. As Ofwat notes, the fact that a company has complied with its regulatory obligations may not be sufficient to demonstrate that it has also complied with the Competition Act 1998; and a defence that the conduct was necessary to comply with regulatory obligations, and cannot therefore fall foul of competition rules, is unlikely to hold in most circumstances.27

All companies must comply with competition law. Agreements among competing retailers not to target each other’s markets would be illegal regardless of the size of the companies concerned. In terms of unilateral conduct, dominant companies have a special responsibility to ensure that they do not abuse their dominant position. Ofwat has previously looked at a number of cases in the water sector to date. While these have not been in relation to retail market opening, they have involved allegations of margin squeeze, predation and discrimination.28

With retail market opening, the main concern is likely to be in relation to leveraging between markets. This may be vertical—if a wholesaler provides a preferential service to its own retail affiliate in order to not lose custom in the retail market then this would fall foul of level playing field rules and, potentially, competition law. It may also be horizontal—in the longer term, retailers may seek to bundle water, electricity and gas, along with value-added services. This may lead to economies of scope and more holistic demand management—with lower prices and better service. But care is required, as bundling can also be used to leverage a dominant position in one market into another—which can damage the competitive process.29

Concluding thoughts

From the start, market opening is likely to involve large multi-site customers actively contracting with retailers to negotiate and secure the best deals. What will happen with small businesses is less certain, given the lack of awareness in the market and the smaller savings on offer. However, this does not mean that retail competition will not be an overall success. Its success will be measured by the improvements in service offerings and lower bills over the medium to longer term. The measure of success for day one of market opening will be if the process goes (reasonably) smoothly.

Switching rates are not a perfect measure of success, as the process of competition may mean that even those customers who do not switch get a better deal than before. However, in terms of both the economics and the politics, over the medium to longer term it will be important for a sufficient number of customers to engage with the market and, in doing so, switch.

Service and price improvements for large customers will result in benefits for smaller customers only if their interests are aligned. If price discrimination is possible, and steep discounts to sophisticated consumers are paid for by the exploitation of smaller customers, the regulator may need to intervene. As discussed in an Agenda article this month on cross-subsidies in the financial services sector, the regulator may wish to ensure that companies’ business models are aligned to consumers’ interests.30

The licence requirements, market codes and regulatory oversight by Ofwat may prevent problems before they take root. Time will tell, but depending on what happens, more customer protection may be needed going forward. In the meantime, the industry has been funding an awareness campaign targeted at SMEs,31 while Ofwat has set out its plan for monitoring progress and any problems.32 Watch this space.

1 The England and Wales water sector comprises a number of water and sewerage companies (WASCs) and water-only companies (WOCs). Non-domestic competition is being introduced in England only, and not in Wales.

2 Ofwat (2017), ‘Market Arrangements Code’, February.

3 See, for example, Ofwat (2017), ‘Consultation on the Wholesale Retail Code: decisions and responses’, February.

4 See Market Operator Services Limited (2017), ‘Assurance Framework and Readiness’; and Open Water (2017), ‘Open Water programme note: one month to go – retail market to open as planned on 1 April’, March.

5 UK government (2014), ‘Water Act 2014’, May.

6 For example, see Water Industry Commission for Scotland (2012), ‘EFRA Select Committee’s Inquiry on the Draft Water Bill: Evidence from the Water Industry Commission for Scotland’, September. See also UK Parliament (2013), ‘Water Bill’, evidence to the Public Bill Committee, 3 December, column 7; and Oxera (2014), ‘Non-household retail competition: Illustrating the possible impact of exit from the non-household retail market’, prepared for The Water Industry Commission for Scotland and Ofwat, March.

7 Wessex and Bristol Water have had a retail JV in place since 2000. This was transformed into a separate entity in 2015. See Bristol Water, ‘About Water2Business’.

8 Oxera provided economic advice to the two parties. For a summary of the issues in the case, see Oxera (2016), ‘Venturing further: water consolidation in England’, Agenda, May. For the case itself, see Competition and Markets Authority (2016), ‘Anticipated non-household retail water and sewerage services joint venture between Severn Trent Plc and United Utilities Group Plc: Decision on relevant merger situation and substantial lessening of competition’, ME/6575/15, 27 May.

9 Competition and Markets Authority (2017), ‘South Staffordshire Water / South West Water Merger inquiry’, March.

10 See Northumbrian Water (2017), ‘Northumbrian Water and Anglian Water join forces to create “Wave” of efficiency and cost savings for business customers’, press release, 23 March.

11 Ofwat (2017), ‘Water UK City Conference 2017, Jonson Cox – Chair, Ofwat – regulatory keynote speech’, March, p. 3.

12 Inset appointments, or new appointment variations, occur where one company replaces another as the statutory supplier for a specific geographic area. Many of these are for new housing developments and new commercial areas. Both incumbent water companies and independent providers have been active in this market to date.

13 Net margin is the profit margin allowed for a retailer, expressed net of both its own retail costs and the price it pays for wholesale services. It is expressed as retail earnings before interest and taxation (EBIT) as a proportion of retail turnover.

14 See Ofwat (2016), ‘Business retail price review 2016: Statement of method and data table requirements’, May, pp. 10–2. Ofwat states that ‘there is no compelling evidence’ that the 2.5% default tariff margin is too low.

15 See Ofwat (2017), ‘Notification that Greene King Brewing and Retailing Ltd. (“Greene King”) has applied for a Water Supply Licence and Sewerage Licence with a self-supply authorisation and proposal by Ofwat to modify the standard licence conditions that will apply to Greene King, if Greene King is granted a self-supply Licence’, January.

16 See Waterscan website.

17 Ofwat (2017), ‘Protecting customers in the business market – a consultation on draft principles for voluntary TPI codes of conduct’, February, p. 8.

18 The Business Protection from Misleading Marketing Regulations (BPMMRs) (2008) prohibit misleading advertising and sales activities.

19 Ofwat (2017), ‘Protecting customers in the business market – a consultation on draft principles for voluntary TPI codes of conduct’, February, pp. 1–5 and pp. 11–8.

20 Ofwat (2017), ‘Protecting customers in the business market – a consultation on draft principles for voluntary TPI codes of conduct’, February, pp. 22–3.

21 Gabaix, X. and Laibson, D. (2006), ‘Shrouded Attributes, Consumer Myopia, and Information Suppression in Competitive Markets’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121:2, pp. 505–40.

22 For an overview of PPI mis-selling, see Financial Conduct Authority (2017), ‘FCA finalise plans to place a deadline on PPI complaints’, press release, 2 March.

23 See Financial Conduct Authority (2016), ‘Interest rate hedging products (IRHP)’, 4 November; and Financial Conduct Authority (2016), ‘IRHP: examples of redress’, 5 May.

24 Opinion Research Services (2017), ‘Ofwat Customer Awareness Survey 2016/17’, Final Report, January, pp. 22–3.

25 For details on fines levied by Ofgem for breaches of licence conditions since 2010, see Ofgem, ‘Investigations and enforcement data’.

26 Ofwat (2017), ‘Protecting customers in the business market – a consultation on draft principles for voluntary TPI codes of conduct’, February, p. 16.

27 Ofwat (2017), ‘Trust in water: Guidance on Ofwat’s approach to the application of the Competition Act 1998 in the water and wastewater sector in England and Wales’, March, p. 33. Oxera responded to Ofwat’s original consultation. See Oxera (2017), ‘Ofwat’s consultation on its approach to competition law in England and Wales: A response from Oxera’, prepared for Ofwat, January.

28 See Oxera (2015), ‘In a fluid state? Competition policy in the water sector’, Agenda, January.

29 See Oxera (2017), ‘Ofwat’s consultation on its approach to competition law in England and Wales: A response from Oxera’, prepared for Ofwat, January, p. 5.

30 Oxera (2017), ‘Should we be cross about cross-subsidies? Experience from the financial services sector’, Agenda, March.

31 See Open Water (2017), ‘National awareness campaign for customers’, 24 January. Resources are available on the Open Water website.

32 Ofwat (2017), ‘Monitoring the business retail market from April 2017: a consultation’, January.

Download

Related

Future of rail: how to shape a resilient and responsive Great British Railways

Great Britain’s railway is at a critical juncture, facing unprecedented pressures arising from changing travel patterns, ageing infrastructure, and ongoing financial strain. These challenges, exacerbated by the impacts of the pandemic and the imperative to achieve net zero, underscore the need for comprehensive and forward-looking reform. The UK government has proposed… Read More

Investing in distribution: ED3 and beyond

In the first quarter of this year the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC)1 published its vision for the UK’s electricity distribution network. Below, we review this in the context of Ofgem’s consultation on RIIO-ED32 and its published responses. One of the policy priorities is to ensure… Read More