To tax or not to tax: will an online sales tax rebalance the retail sector?

The growth of online sales has prompted debate around whether an online sales tax (OST) should be introduced to ‘rebalance’ the taxation of the retail sector. Indeed, the evolution of retailing in the UK has implications for several key government policy areas. We revisit the topic, which we explored in a 2020 Agenda article,1 in light of the recent launch of an HM Treasury consultation on the introduction of an OST.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the online retail sector has provided an essential service to the public. Businesses on the high street have faced unique challenges, with closures, reduced footfall and ongoing uncertainty, and with many of these retailers turning to the online market to continue operations.

While the high streets have now reopened, the pandemic accelerated trends that were ongoing over recent decades. These trends include changes in the use of high streets, the growth of supermarkets, moves to out-of-town shopping centres and retail parks, and the growth of online sales. This evolution of retailing in the UK has implications for several key government policy areas—one of which is taxation, where numerous debates have emerged in recent years.2 In particular, the growth of online sales has prompted debate around whether an online sales tax (OST) should be introduced to ‘rebalance’ the taxation of the retail sector.

The HM Treasury consultation

Increasing expenditure online and changes to the way that people use high streets have led to business rates (see the box below) falling over time in terms of contribution to government total taxation receipts.

What are business rates?

Business rates are a form of taxation levied on the occupiers of commercial properties. In the UK, it is the most important tax on commercial property. It acts like an extra rental payment that has to be made to the state, in addition to the rent payable to the landlord. It is also payable by owner-occupiers, calculated as if they were renters.

In July 2020, HM Treasury launched a fundamental review of business rates, with the aim of establishing a sustainable revenue source for government that would better reflect modern society.3 At the time, one of a number of alternative revenue sources explored was the introduction of an OST.

The introduction of an OST is now the focus of a consultation launched by HM Treasury in February.4 In the July 2020 consultation, the Treasury initially proposed an OST as a replacement for the declining revenues from business rates. This differs somewhat from the recent consultation, in which the Treasury set out its aim for the taxes to exist alongside each other. Indeed, HM Treasury notes that an OST levied at 1% or 2% of the value of an online purchase would not raise sufficient revenue to replace the business rates levied on retailers in full, as a 1% OST would generate approximately £1bn per year for the Exchequer, compared to £25bn for business rates.5

Before exploring the merits of an OST, it is important first to address issues around fairness that have emerged alongside the debate about online sales taxation. These are explored in the box below.

Is the current taxation system fair?

A key reason for the consideration of an OST, as highlighted by the responses published in the Treasury’s interim report, was to address ‘fairness’ in the tax burden faced by offline retailers.* This stems from the perceived notion that online retailers face an unfair tax advantage over high street sellers.

The notion that there is a tax advantage to operating online appears to conflate several issues.

- Foreign vs domestic tax advantages—where companies domiciled in certain countries achieve advantages arising from less effective corporate taxes. This generalisation cannot be made for all online retailers—the majority of the top ten retailers responsible for online sales in the UK are companies that are domiciled in the UK and therefore subject to UK taxation.**

- Digital economy vs online retail—the challenges associated with taxation of the digital economy should be seen as distinct from the taxation of online retailers. The former includes technology companies whose main revenue source relates to the provision of digital services. In this sector, tax challenges arise from the difficulty of defining tax jurisdiction and the problem of attributing value to data created by users free of charge, among other things.*** This contrasts to online retailers, which sell goods and services online, and for which the value chain can be more easily identified.

- The changing face of the high street—the retail industry has evolved over the past few decades, reflecting changing consumer patterns and tastes. The decline of the high street has often been touted as a direct consequence of the growth of online sales. However, the challenges facing the high street predate the proliferation of online retail, and such narratives often ignore the importance that online sales play for many bricks-and-mortar retailers that are increasingly turning to a hybrid ‘omni-channel’ model. The taxation of online sales could therefore penalise such hybrid retailers that are looking to expand their online offering. Indeed, the consultation highlights that the shift from in-store to online has been seen globally, and therefore not just in the context of the UK business rates.

- Fairness of competition—competition is not always ‘fair’, as it rewards businesses that are more efficient and more innovative. In many instances, lower costs relate to higher efficiencies offered by certain business models, including the online sales model, which then allows for products to be provided more cheaply—for example, by not relying on the heavy use of property, which can benefit consumers (through lower prices, as well as the convenience of shopping online).

Source: * HM Treasury (2021), ‘Business Rates Review: Interim Report’, March, para. 3.116. ** The top ten retailers by net sales are Amazon, Very, Ocado, Currys, Next, John Lewis, Argos, Tesco, Sainsbury’s, and Asda. See ecommerceDB (2021), ‘Store Ranking & Overview United Kingdom’. *** Ibid. **** HM Treasury (2022), ‘Online sales tax: assessing an option to help rebalance taxation of the retail sector’, February, para. 1.11.

What is an online sale?

To understand the implications of an OST, the first relevant question is: what does an ‘online sale’ actually capture? While the Treasury’s consultation engages with the issues of design and practical implementation, the precise nature of an OST is not yet specified.

As explained in our 2020 Agenda article,6 the definition of an online sale matters. We discussed questions such as the following.

- How would a ‘click-and-collect’ sale be treated, as compared to a sale with a delivery option?

- Should only goods be included in the scope, or also services (and what about bundled purchases)?

- What about exemptions for certain goods (as is the case with VAT)?

- Should business-to-business sales be excluded from the scope in the same way that VAT is?

These types of definitional questions are very important for understanding what the tax base is, and also who will be affected by a new taxation. The Treasury is exploring these questions in its consultation.

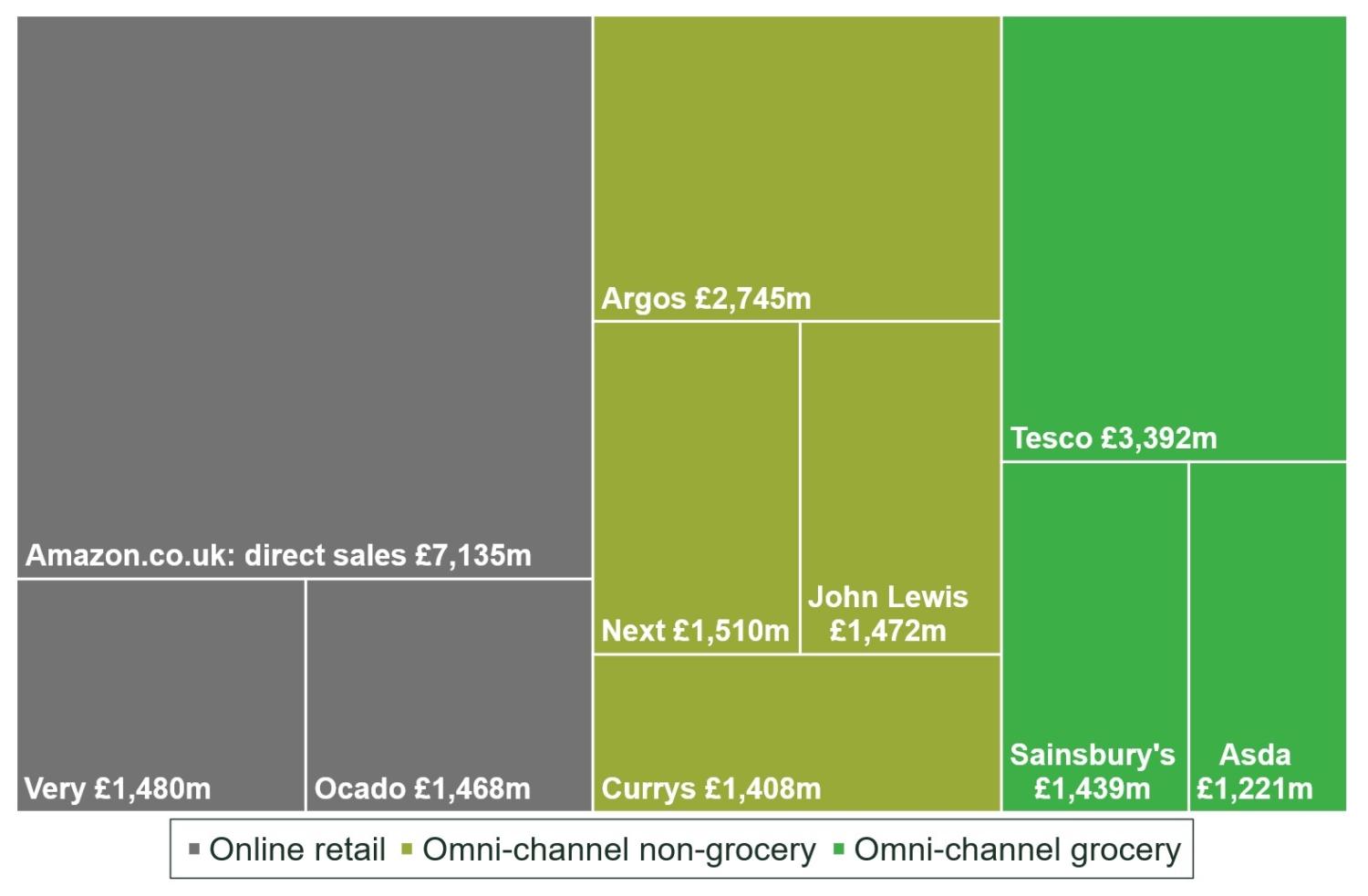

Understanding what makes up online sales helps us to establish who the tax will affect and where any distortions will lie. Figure 1 below shows that of the ten largest online retailers in the UK, eight were omni-channel businesses (retailers that have both an online and a bricks-and-mortar presence). Since most online retail is conducted by omni-channel retailers, an OST will affect high street outlets that have either expanded online or plan to do so.

Figure 1 Net sales of top ten online retailers in the UK (£m)

Source: ecommerceDB (2021), ‘Store Ranking & Overview United Kingdom’.

What is the case for and against an online sales tax?

The merits of an OST can be assessed against a range of government policy objectives, as set out in the box below.

Government policy objectives

Governments around the world levy taxes on businesses to achieve various policy objectives. Grouped by themes, policy objectives can include:

- direct costs and benefits—revenue-raising, increasing the enforcement/collection rate, and minimising the cost of administration;

- supporting businesses—rejuvenating the high street and/or rebalancing the retail sector, boosting the international competitiveness of UK businesses, and addressing considerations of economic efficiencies;

- wider societal benefits—promoting innovation, supporting employment, and pursuing environmental objectives. Different types of tax will contribute to different policy objectives—indeed, objectives may compete with each other, giving rise to trade-offs.

We briefly assess the OST against these objectives, as well as reflecting on some of the practical design questions that the recent consultation raises.7

Revenue raising

The revenue potential of an OST is largely determined by two things: (1) the tax base (i.e. the sales value of goods and services that the tax applies to); and (2) the rate of the OST. The sales value of the goods and services that the tax applies to is also a function of the tax rate, as the pass-through of the tax into consumer prices will have an effect on the prices and volumes of sales.

Clarity surrounding what exactly constitutes ‘online sales’ will be important, given the impact that the tax will have on raising revenues—since a narrower definition implies a lower revenue base.

If OST is levied as an ad valorem tax, rather than a lump sum tax or a flat fee, the economic effects are likely to resemble that of VAT. If exemptions are applied in a similar way to VAT (such as on food items), this would then serve to limit the revenue-raising potential of any new OST.

Enforcement and collection rate

The administrative burden of introducing an OST will depend on the definitional issues associated with establishing what exactly constitutes ‘online’, as explored earlier in this article. We note that HM Treasury is alive to such issues.8 It notes that an OST would require its own administrative framework.9 Complex taxes, including VAT, can lead to a significant additional cost burden to government, with call centres and officers checking calculations. Given the potential similarities between an OST and VAT, this issue may be present here.

Rebalance the retail sector

The 2020 consultation highlights that a number of stakeholders have called for an OST to rebalance the retail sector. The 2022 consultation proposes that an OST can be used to assist some bricks-and-mortar businesses by funding a business rates cut for the retail sector. This represents a simplistic view of the retail market, as a significant number of traditionally bricks-and-mortar shops now offer significant online sales, with online-only retailers playing a relatively smaller role.

This demonstrates the integrated nature of the retail industry, illustrating that rebalancing between online and offline would actually mean a large number of businesses facing a new OST and reduced business rates at the same time. We note that the consultation puts forward the design question of whether a threshold or allowance for smaller firms or firms with a lower proportion of sales made online should be introduced.

We note that wider concerns about the changing retail landscape, and in particular rejuvenating high streets, could be better addressed by policy that is targeted at the design of public spaces, where the public are increasingly seeking a leisure experience rather than simply visiting a series of shops.10

The international competitiveness of UK businesses

The consultation raises the issue of international competitiveness by exploring the implications for cross-border sales.11 Where UK businesses face an additional administrative burden for their online sales, or in transitioning to provide online sales, the additional burden of an OST will reduce their competitiveness and slow down their growth in serving international customers relative to international competitors.

Economic efficiencies and distortions

The introduction of an OST is likely to give rise to a number of different effects. This ranges from the price of online goods increasing, favouring offline purchases over those made online,12 to distortions created between different types of business models, favouring bricks-and-mortar or even certain channels (e.g. click-and-collect, rather than delivery), depending on the implementation of an OST. Cuts to business rates for retailers only (as opposed to hospitality, for example) will create distortions between sectors that are competing for the same type of property on the high street.

It is unclear how retailers that operate websites that include options for both delivery and ‘click and collect’ will be affected by such tax reforms. Accordingly, the implementation of tax reform relating to the sale of online goods is likely to give rise to a number of challenges, particularly for omni-channel retailers.

The consultation raises the question of whether any exemptions would be appropriate, such as for click-and-collect purchases or for certain goods and services.13 To the extent that there are exemptions, this creates a bias towards the goods that fall outside of the scope of the new tax, favouring some sectors over others. It is also likely to create distortions between different types of consumers, penalising consumers who, for a variety of reasons, rely more on online sales—this includes the young, those less able to travel, and those living in rural communities.

The consultation notes that tax structure is important: should the tax be a flat fee or an ad valorem tax? These different structures will introduce different distortions. Indeed, introducing an OST as an ad valorem (revenue tax) will have a similar effect to that of VAT—that is, an OST will directly affect prices, and therefore equilibrium consumption quantities. A flat fee structure means that the same tax is paid per order, regardless of the size of the order (in terms of both volume and value). As a result, a tax levied in this way will cause distortions relating to order size, incentivising consumers away from buying low-value goods or making multiple low-value purchases. In this way, a charge per delivery could encourage people to make fewer, larger orders.

Wider social benefits

The introduction of an OST can also be assessed in relation to its likely impact on wider social benefits, including on innovation and the environment.

In relation to innovation, the face of traditional bricks-and-mortar retail is evolving, adapting to changing consumer needs and preferences. This is recognised in the consultation, with HM Treasury noting its desire not to stifle innovative business practices.14 We note that the retail sector is marked by the increasing integration of digital and physical sales channels; the additional burden of an OST may distort the incentives around such innovation by preventing or slowing down the development of online innovative customer solutions and retail experiences.

The consultation also raises the question of the environmental impact of an OST.15 Consistent with the consultation, we note that a clear consensus on the net environmental impact of online retail does not exist. The largest environmental benefit from online shopping is argued to come from transport, as a single delivery trip can replace several shopping trips. However, innovations such as same-day and last-mile delivery have negative environmental consequences due to the frequency and number of deliveries made.16

The challenges ahead

The practical implementation of an OST is likely to be challenging, as our research and the recent HM Treasury consultation show. Indeed, the suitability of an OST for meeting UK government objectives will vary depending on the scope and implementation of an OST.

As a result, any changes in taxation should be considered in light of policy trade-offs, as well as whether the desired policy objectives can be achieved through other, less distortive means.

1 Oxera (2020), ‘Will an online sales tax save the UK high street?’, Agenda, September.

2 Oxera was commissioned by a large online retailer to provide an independent economic policy report exploring tax reforms relating to the potential introduction of an OST, among other potential tax changes.

3 HM Treasury (2021), ‘Business Rates Review: Call for evidence’, July.

4 HM Treasury (2022), ‘Online sales tax: assessing an option to help rebalance taxation of the retail sector’, February.

5 Ibid., paras 1.16 and 4.10

6 Oxera (2020), ‘Will an online sales tax save the UK high street?’, Agenda, September.

7 HM Treasury (2022), ‘Online sales tax: assessing an option to help rebalance taxation of the retail sector’, February, para. 1.18.

8 Ibid., para. 2.4.

9 Ibid., para. 3.41.

10 Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government (2021), ‘Build Back Better High Streets’, July.

11 Ibid., para. 3.11.

12 The extent of any price increase is determined by the degree of pass-on to the final consumer—i.e. the tax incidence.

13 HM Treasury (2022), ‘Online sales tax: assessing an option to help rebalance taxation of the retail sector’, February, para. 4.21.

14 Ibid., para. 4.16.

15 Ibid., question 40, ‘What environmental impact might an OST have? How would its design affect an OST’s environmental impact?’.

16 ‘Last-mile delivery’ refers to the movement of goods from a transportation hub to the final delivery destination.

Related

Investing in distribution: ED3 and beyond

The National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) has published its vision for the UK’s electricity distribution network. Below, we review this in the context of Ofgem’s consultation on RIIO-ED31 and its published responses. One of the policy priorities is to ensure that the distribution network is strategically reinforced in preparation… Read More

Leveraged buyouts: a smart strategy or a risky gamble?

The second episode in the Top of the Agenda series on private equity demystifies leveraged buyouts (LBOs); a widely used yet controversial private equity strategy. While LBOs can offer the potential for substantial returns by using debt to finance acquisitions, they also come with significant risks such as excessive debt… Read More