Unbundling: what’s the impact on equity research?

The EU’s second Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID II), introduced in January 2018, requires brokers to charge separate fees for trade execution and for research, thereby ‘unbundling’ them. Since these rules came into force, there have been concerns about their impact on the provision of research and, more generally, the development of capital markets. What market failures does the unbundling rule intend to address, and what are its potential unintended consequences?

Investors pay fund managers a fee in return for management services. For example, a fund may have an annual management charge of 0.5%, which would mean that the fund manager receives a payment of 0.5% of the value of the assets under management each year. This fee is visible to investors and is included in the total expense ratio (a common metric used by investors to determine if a fund is an appropriate investment for them after fees are considered). In addition, fund managers pay brokerage dealing commissions, which are taken directly from the fund value.1

Pre-MIFID II, in return for dealing commissions, fund managers would receive not only trade execution services, but also additional goods and services (predominantly ‘research’) from their brokers. The terms on which these extra services were provided were not always explicitly agreed, but there was usually an understanding that the investment manager would generate a certain amount of business for the brokers in exchange for receiving the extra services.

This practice can be traced back to the fixed brokerage commission rates of the 1960s and 1970s. At that time, because brokerage commissions were fixed, brokers competed for trade execution business on the basis of other goods and services provided to the manager (‘free of charge’) for directing trades to that broker. Although the era of minimum commission rates has long since passed, the practice of bundled brokerage arrangements has continued.

The regulatory concern with bundled brokerage arrangements is that the research may be an inducement for the fund manager to send trades to a broker. In other words, rather than sending trades to the broker that would be best at executing the trade, fund managers would have an incentive to select brokers based on the quality and quantity of their research.

The best execution rules under MiFID II may have addressed some of these issues, but concerns about the quality of the research and potential overconsumption of research have also been raised. As the commissions come directly out of the fund value, they do not affect the fee revenues received by the fund manager, and therefore the fund manager may be less concerned about whether the services are really needed by the fund. This is likely to be a particular issue where the fund manager is able to move expenses (that they would otherwise have had to pay themselves—such as the costs of attending conferences) to commissions, where the fund rather than the fund manager pays for them directly. In economics jargon, the interests of the agent (the fund manager) are not necessarily aligned with those of the principal (the fund).

Furthermore, there was a concern that this practice would put certain players—such as execution-only brokers and third-party research providers—at a competitive disadvantage compared with brokers offering a bundle of trade execution services and research.2

In some countries, some of the concerns about bundling trade execution and research were addressed, pre-MiFID II, by requiring fund managers and brokers to specify what proportion of the commissions was spent on trade execution and what proportion on research. This was facilitated by putting commission sharing arrangements (CSAs) in place. Such arrangements also enabled the fund managers to use some of the commissions (‘soft commissions’) to pay for research from third parties—such as another broker or a research provider—thereby creating more of a level playing field between different types of provider. Fund managers were also required to disclose their CSAs to their clients to facilitate monitoring of how their money was spent. Furthermore, the types of services that could be purchased with commissions were restricted to ‘research’ to prevent fund managers from using commissions to pay for services (such as market data or conferences) other than trade execution and research.

The role of equity research

Before analysing the potential impact of the new rules on unbundling, it is useful to look at the economics of the market for equity research.

The availability of accurate and timely information for the various market participants is crucial if equity markets are to function effectively. However, the volume and complexity of the information relating to companies’ future prospects make it extremely costly, if not impossible, for each investor to filter through and interpret every piece of available information. This is particularly true for private investors, but also, to some degree, for trustees of institutional investment funds.

There are economies of scale and specialisation in the analysis of company information. It could, therefore, be efficient to have a market in which a number of specialised analysts research the raw data on firms and industries, form an opinion on the future prospects of the firms, and disseminate that analysed information to investors. In this way, costly duplication of research efforts can be avoided, while at the same time, the number of analysts covering a particular company and industry can still be large enough to allow for different views on the more subjective aspects of the research.

Indeed, this is very similar to the way in which the market has evolved over the years, in that research is currently produced by brokers, independent research houses, and in-house fund managers.

Equity research can help to highlight opportunities for investment that may otherwise be less visible, particularly where the research goes beyond traditional valuation metrics. Research can provide investors with a valuable consolidated source of information not found in a company’s own financial reporting—offering a second opinion that can support or challenge a firm’s own claims about its future prospects, as well as providing an important broader (e.g. industry or macro) context.

Empirical analysis confirms that, for listed companies, it is important to be covered by sell-side analysts,3 and that reductions in equity research coverage can result in less efficient pricing and lower liquidity, more volatile trading around subsequent earnings announcements, and increases in required returns.4

This means that the dissemination and pricing of research is affected by a potential market failure. Market efficiency—i.e. equity prices being in line with the underlying fundamentals of the company—is enhanced if all (or most) investors have access to all (or most) of the relevant information. The information disseminated by companies has the characteristics of a positive externality: the social benefit of production is greater than the private benefit, because there are beneficial spillovers of market research to third parties that may not pay for the research. The external benefits stemming from greater research coverage include the improved market liquidity and lower cost of capital for companies. This is supported by empirical analysis, which suggests that coverage positively affects company prospects and valuation.5 In normal market conditions, where market participants do not take into account such positive externalities, there would be a risk of under-provision of research.

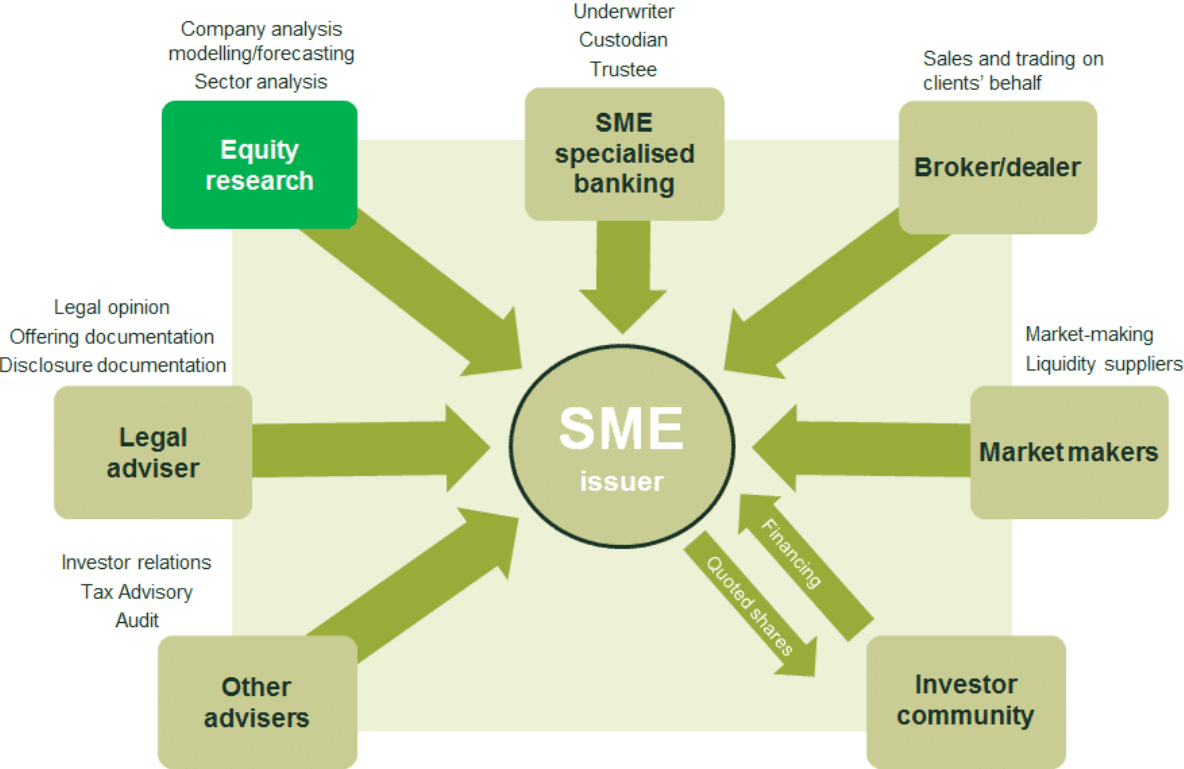

It is well understood by policymakers that equity research is an important element of developing a healthy ecosystem for SMEs’ equity finance (see Figure 1). Research providers for SMEs need to be able to tell investors the whole story about a company, rather than just provide key financial metrics that are generally publicly available.

As explained in the European Commission’s economic analysis on Capital Markets Union (CMU),6 equity research is particularly important for SMEs, given that they have lower visibility and information is more opaque and scarce than for other companies. The Commission’s analysis goes on to describe how, despite the clear need for equity research on SMEs, a market failure exists, as analysts tend to ‘orient their coverage to large caps…as research on large caps is more profitable’.7 Many SMEs, particularly at smaller market capitalisation sizes, have little research other than from their broker. A lack of research reduces the likelihood of attracting investment.

Figure 1 The ecosystem for SME equity offerings

Potential impact of unbundling

MiFID II did not adopt the regulatory practice of CSAs and disclosure described above. Instead, it went further, requiring fund managers and brokers to set separate charges for trade execution and research, and fund managers to pay for research themselves (i.e. recovering the costs through the annual management charge) or agree a separate research charge with their clients.

At first sight, this seems to address the concerns set out above. There will no longer be an incentive for fund managers to overconsume research and to send trades to the brokers who provide them with the most or best research. Where to trade and where to purchase research will become separate decisions, as fund managers will now need to pay for research themselves rather than out of commissions (or charge clients a separate research fee).

The evidence suggests that commission rates have come down following the implementation of MiFID II.8 This was expected, since research is no longer paid for out of commissions and its cost needs to be explicitly disclosed to the clients of the fund managers. There is also some evidence that the separate payments for research by fund management firms to brokers and independent research houses are less than the reductions in commissions, and this could be seen as evidence of overconsumption pre-MiFID II and the new rules having an impact.

However, the new rules on unbundling may also have resulted in some unintended consequences.

First, although MiFID II is intended to address the concerns about inducements (i.e. preventing brokers from competing on the basis of ‘free research’), there is another market failure: that relating to the positive externality of production of research. This positive externality of production remains, and is likely to result in under-provision of research, particularly in relation to SMEs. The new rules on unbundling do not address this, and may further expose the market failure relating to the under-provision of high-quality research on small companies. The over-provision of research pre-MiFID II is most likely to have related to ‘low-quality’ research and to have focused on larger companies.

After full implementation of the MiFID II rules, this may leave the market overall, and particularly SMEs, with an under-provision of research.

The second issue is that although separate charges need to be set for trade execution and research, and fund managers are no longer allowed to receive research for ‘free’, brokers may still have an incentive to offer research at very low (but not zero) fees, and potentially below cost, by using trade execution revenues to cross-subsidise the provision of research.9

This has the following potential implications.

- Brokers who offer research may have a competitive advantage over execution-only brokers and independent research providers. In other words, the new rules may reintroduce the distortion in the level playing field between different types of provider, which, in some countries, the introduction of CSAs had managed to address.

- Due to their scale, very large brokers may be more able to set very low fees and/or use trade execution to cross-subsidise the provision of research than small or medium-sized brokers. Indeed, some of the evidence to date suggests that very large brokers have managed to offer research at very low fees, meaning that fund managers have switched away from small and medium-sized brokers for the procurement of research.10 Concerns about large multi-service brokers internally cross-subsidising their research were also raised in a recent survey undertaken by the FCA in the UK.11

In other words, the new rules may not have fully addressed the inducement issue, and may have reintroduced a distortion of competition between larger brokerage firms, and smaller brokers and independent research houses.

If most of the research were produced by a smaller number of very large brokers, this could potentially also have a negative effect on the diversity of the research, which would have a disproportionate impact on local, smaller and newer research providers due to the economics of appraising smaller companies.

The concern would be that the very large brokers would focus on the larger and more actively traded firms (where their profitability is typically higher), which would contrast with the smaller and more localised brokers and boutique research houses, which would typically specialise in local markets and smaller companies.

Reduction in research coverage of SMEs

Recent market developments indicate that the new unbundling rules may indeed deter brokers from providing research coverage on SMEs. For example, a recent analysis finds a decrease in sell-side analysts covering European firms since the implementation of MiFID II, with 334 SMEs losing their analyst coverage completely.12 Although the FCA survey of fund management firms in the UK13 suggests that only a few firms had seen a reduction in research on SMEs, while a majority had not, a larger survey finds that 62% of investors believe that less research is being produced on SMEs since MiFID II came into effect.14 Data published by Reuters indicates a clear reduction in the number of analysts per company following the major European MSCI small cap indices.15

What next?

The European Commission has committed to assessing the impact of the MiFID II rules on equity research on listed SMEs, and has already commissioned a study that will assess the impact on the availability of research before and after the implementation of MiFID II, the quality and price of research, and SME access to finance.16

While these points are clearly relevant for an ex post review on this issue, there are some additional important aspects that would need to be examined:

- the issue of cross-subsidisation and the nature of competition between the larger and the small and medium-sized brokers, and between brokers and independent research providers. The FCA in the UK has indicated that it will review how sell-side pricing models are developing in 12–24 months’ time;17

- the question of how to develop the market for research, particularly for new and growing companies.

Ultimately, a post-implementation review should evaluate how the unbundling rules have affected competition for the provision of research and, more broadly, the functioning of financial markets—particularly equity markets.

1 Brokerage dealing commissions are fees that fund managers pay to brokers for trade execution services.

2 This issue was identified in Oxera (2003), ‘An Assessment of Soft Commission Arrangements and Bundled Brokerage Services in the UK’, April. Furthermore, in some countries, trade commissions are not subject to VAT, which would mean that it is more tax-efficient to pay for the research from brokers out of commissions, putting third-party research providers at a competitive disadvantage.

3 A survey undertaken among 344 buy-side analysts from 181 investment firms in the USA or Canada. Brown, L.D., Call, A.C., Clement, M.B. and Sharp, N.Y. (2016), ‘The Activities of Buy-Side Analysts and the Determinants of Their Stock Recommendations’, Journal of Accounting & Economics, 62:1, August, accessed 10 September 2019.

4 On announcement that a stock has lost all coverage, share prices have been found to fall, on average, by 110 basis points. Kelly, B.T. and Ljungqvist, A. (2012), ‘Testing Asymmetric-Information Asset Pricing Models,’ The Review of Financial Studies, 25:5, May, pp. 1366–1413, accessed 10 September 2019.

5 For example, see Womack, K.L. (1996), ‘Do Brokerage Analysts’ Recommendations Have Investment Value?’, The Journal of Finance, 51:1; Jegadeesh, N., Kim, J., Krische, S.D. and Lee, C.M.C. (2004), ‘Analyzing the Analysts: When Do Recommendations Add Value?’, The Journal of Finance, 59:3; Kelly, B.T. and Ljungvist, A. (2007), ‘The Value of Research’, NYU Working Paper.

6 European Commission (2017), ‘COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT Economic Analysis Accompanying the document COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS on the Mid-Term Review of the Capital Markets Union Action Plan’, SWD(2017) 224. Hereafter, ‘SWD(2017) 224’.

7 SWD(2017) 224, pp. 46–47.

8 See Greenwich Associates (2019), ‘Global equity trade execution rates decline in the wake of MiFID II’, press release, 29 January, accessed 25 June 2019; and Mooney, A. and Murphy, H. (2018), ‘Banks and brokers suffer “dramatic” fall in commissions’, Financial Times, 2 June, accessed 25 June 2019.

9 This issue was identified by Oxera (2014), ‘A new approach to conduct risk? The example of soft commissions’, Agenda, September.

10 See Kinder, T. (2017), ‘FCA sets sights on price-dumping in research market’, Financial News, 16 October, accessed 25 June 2019; and Flood, C. (2018), ‘FCA to launch asset management Mifid probe’, Financial Times, 18 June, accessed 25 June 2019.

11 See Financial Conduct Authority (2019), ‘Implementing MiFID II – multi-firm review of research unbundling reforms’, 19 September, accessed 18 October 2019.

12 Fang, B., Hope, O.-K., Huang, Z. and Moldovan, R. (2019), ‘The Effects of MiFID II on Sell-Side Analysts, Buy-Side Analysts, and Firms’, Rotman School of Management Working Paper No. 3422155, accessed 10 September 2019.

13 Financial Conduct Authority (2019), op. cit.

14 QCA/Peel Hunt (2019), ‘MiFID II: The Search for Research, Mid and Small-Cap Investor Survey’, February.

15 Pal, A. (2018), ‘UK stocks coverage shrinks after new research rules’, Reuters, 29 June, accessed 13 September 2019.

16 FISMA (2017), ‘Call for tenders: Study on the impact of MiFID II rules on SME and fixed income research’.

17 Financial Conduct Authority (2019), ‘Statement on MiFID II inducements and research’, 8 November.

Download

Related

Measuring and inferring anticompetitive effects from an exchange of information

In four rulings1 dated 3 November 2025, the Spanish National Court overturned the Decision of the Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia (CNMC) in case S/DC/67/17 Tabacos2 (‘the Decision’). These four rulings are significant because they close one of the first cases that the… Read More

Decoding the Digital Networks Act: the future of the EU electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework

On 21 January 2026 the European Commission published the long-awaited draft of its Digital Networks Act (DNA)—the proposed new regulation that seeks to ‘modernise, simplify and harmonise EU rules on connectivity networks’.1 As the draft is now being reviewed by the European Parliament and the Council, representing the… Read More