Washing out greenwashing: regulation and investment for a net zero future

What is the role of regulation in nurturing new markets for environmental, social and governance (ESG) investment? ESG investing has grown significantly in recent years as investors look for sustainable and ethical opportunities. This has generated issues such as financial ‘greenwashing’, whereby products are mis-sold as being more sustainable than they truly are. We take a closer look at the growth of ESG investing and the development of regulations and standards to combat financial greenwashing.

How can funds invest with impact? Is it possible to invest with a social agenda while generating returns for investors? What standards should there be for environmental, social and governance (ESG) compliant investments? These questions are becoming ever more relevant as flows into ESG-branded investment products have grown significantly in recent years.

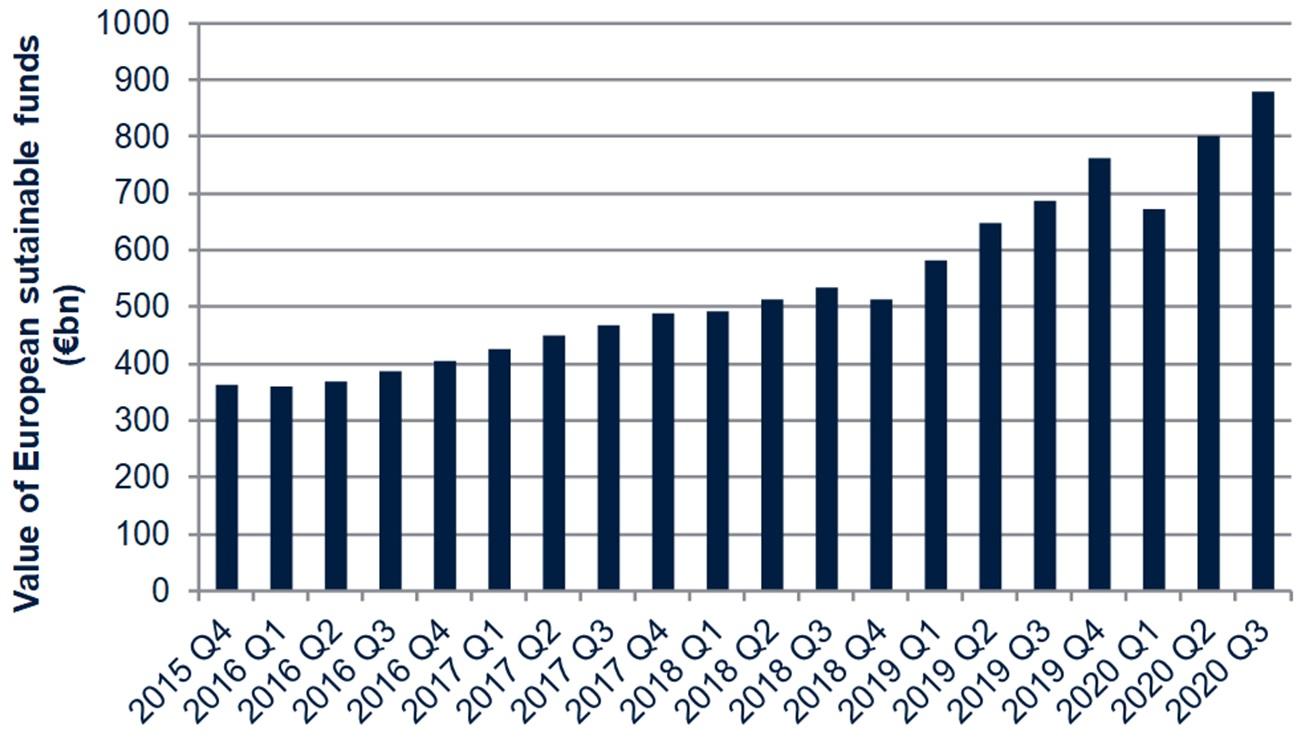

As shown below, the value of sustainable investment funds almost tripled between 2016 and the end of 2020, with the momentum behind ESG investing continuing to increase in the wake of high-profile events such as COP26 in November 2021.

Figure 1 Value of European sustainable investment funds (2015–20)

Source: Bioy, H. (2020), ‘ESG Funds Assets Hit £800 Billion’, Morningstar, 9 November.

As highlighted at COP26, the mobilisation of large amounts of private finance will be necessary to facilitate the green transition. Vast sums have been pledged as part of this. For example, the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, led by former Bank of England Governor Mark Carney, announced that its members, a number of financial institutions with assets totalling over $130trn, have pledged to support the global transition to a net zero economy.1

There is an important question as to how ESG funds should be regulated. Over the years, many new investment products and funds have been launched across the world to capitalise on the attention and financial backing that the ESG movement has received. While many of these funds are transparent, some have been found less true to the principles of ESG than required—performing so-called financial ‘greenwashing’, whereby a fund is branded as sustainable when in reality it is not. While the use of this term developed in response to its appearance in the consumer goods sector, it also applies when referring to financial products, where investors can be misled by the branding and specifically the naming of products.

We look at the development of new regulations to combat greenwashing, how both public and private regulations and standards interact, and which aspects of the regulations are particularly important to get right.

Rolling out regulation

The market for ESG-orientated investment products has expanded rapidly over the past two decades. Between Q1 2019 and Q1 2021, the size of inflows into sustainable funds grew by nearly four times globally, with more than 80% of the growth occurring in Europe.2 It is forecast that ESG-compliant assets under management could hit a total value of $53trn by 2025, or around one-third of the global total.3

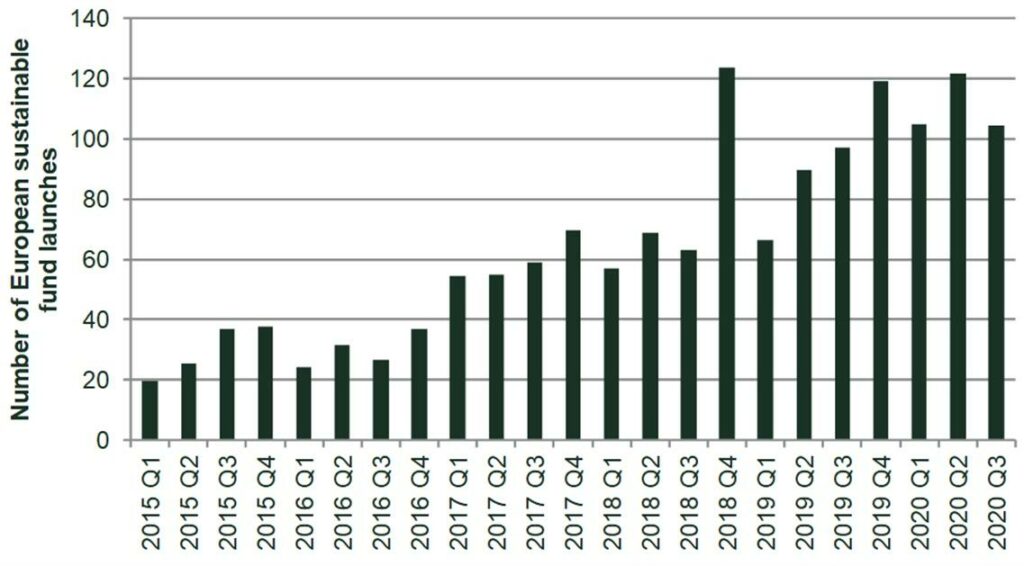

Figure 2 Number of European sustainable fund launches per quarter (2015–20)

Source: Bioy, H. (2020), ‘ESG Funds Assets Hit £800 Billion’, Morningstar, 9 November.

With a market as nascent and fast-growing as sustainable investing, it is probable that some funds will not adhere to the highest-quality ESG principles, and their methodology for tracking and maintaining standards will not be as robust as others. The lack of agreed ESG standards and compliance is a major inhibitor of the development of this market, and regulations on the quality of ESG investments and standards for reporting on them will be needed.

This issue was raised by Sacha Sadan of the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) during a panel at COP26. He highlighted the need for better regulation to enable the ESG market to grow and develop, so that it might eventually reach a more mature stage.4 Further regulation, Sadan claimed, is needed to combat the rise of ‘greenwashing’ in the financial sector.

This matter was discussed by the FCA in a letter to authorised fund managers. The letter made the case for clarity and reliability to maintain investor confidence in the products they are buying, and to ensure that these sustainability-focused financial flows remain available.5

While the FCA currently challenges firms at the point of their authorisation, it argues that more needs to be done to make the initial applications more rigorous. The rationale for this is that the FCA must protect consumers from being mis-sold products—but the implication is that the FCA must be able to assess products objectively and reliably against standards of ESG compliance to develop trust and reliability in the market, and to ensure that the funds required for the green transition continue to be mobilised and invested where they will achieve real climate impacts.

In light of these challenges, independent standards organisations, regulators and governments around the world are putting forward initiatives to clarify what an ESG-compliant investment product can be.

The EU’s sustainability-related disclosures in the financial services sector (SFDR), adopted in 2019 and applicable from March 2021, seeks to create disclosure requirements for all financial products that pursue the objective of sustainable investment.6 In the UK, the FCA has opened up a consultation on Sustainability Disclosure Requirements, including investment labels and consumer-facing disclosures for ESG-compliant investment products.7 This consultation was itself in response to the UK government’s policy paper ‘Greening Finance: A Roadmap to Sustainable Investing’, which seeks to make robust, consumer-facing and credible sustainability disclosure mandatory for investment products.8

Financial regulators in other countries, such as Switzerland and Sweden, have also put forward proposals to tackle financial greenwashing, and have put forward research as members of organisations like the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO).9

Furthermore, the International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation (IFRS), a body set up originally to formulate robust accounting principles for use internationally, announced the creation of a separate arm, the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), to produce sustainability-related disclosure standards.10 This will consolidate previous work undertaken by the Value Reporting Foundation, which created the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) to develop the SASB Standards, which were released in 2018.11 These standards outline financially material sustainability information in disclosure guidelines bespoke to specific industries.

Too much noise in the ESG ratings marketplace?

Despite these efforts to generate robust and consistent reporting standards and ESG frameworks, there is a risk that the wide variety of ESG classifications produced by various ratings agencies and maintainers of ESG indices could lead to increased noise in markets, making it more (rather than less) difficult for investors to assess the sustainability of an investment. Numerous sources cite a wide divergence and lack of common standards in ESG ratings and certification, which can then lead to mixed signals for companies trying to improve their ESG performance.12

One of the major issues in designing consistent ESG compliance regulations is that of metrics. As is the case with any regulation, the metrics that are used to assess a firm’s or investment’s performance must be reliable. It will be difficult to ensure that the metrics used are not easily distorted by the institutions creating investment products. For example, when assessing the emissions of an individual firm as scaled to their size, using a measure such as revenue or enterprise value to compare the size of different firms could be manipulatable.

While it would be necessary to scale the emissions of a firm to make them comparable, it would also expose the metric to the risk of being manipulated, as the denominator, revenue or another measure of corporate size could be inflated to artificially reduce the apparent climate impact of the firm. Avoiding manipulatable metrics like these will be an important task when formalising the definition of ESG compliance.

This is where the role of reporting standards comes in, as ensuring that the data firms report to investors is comparable and reliable matters when determining the climate impact of a firm. The Sustainable Accounting Standards Board’s (SASB) methodology and definitions for consistent accounting of a firm’s sustainability has been adopted by many large organisations wishing to report their environmental impact and sustainability in a consistent and transparent way. SASB has highlighted that its role is to make the ESG frameworks of ratings agencies and investors actionable by ensuring that they are supplied with reliable data.

Regulating sustainable investment

This effort to better regulate the ESG investment market will be crucial in the overall approach to tackling carbon emissions and climate change, alongside further social and corporate governance issues.

One of the major focuses of COP26 was on securing the support of international finance to make sure that there is the necessary capital to build the infrastructure, scale the technologies and support the businesses that will undertake the green transition. This was the reasoning behind ‘Finance Day’ at the conference, where speakers from across the public and private sectors spoke on the need to mobilise financial resources to address the climate crisis, and where institutions with more than $130trn of assets under management committed to help fund the pathway to net zero.13

To ensure that these funds and other investments are environmentally accountable and effective in facilitating the green transition, the new standards and regulations proposed by the FCA and other bodies must allow investors to rigorously assess different investment products on robust disclosures. Making sure that these regulations are rolled out quickly—but with the necessary requirements—will be a difficult but highly important step in making sure that finance is available on the scale and with the right direction needed to meet the challenge of achieving net zero.

The market for sustainable investing has grown rapidly in the last few years as a symptom of growing awareness of the issues of climate change and the need to decarbonise the economy. Many asset managers and owners have taken this opportunity to invest with impact, thinking about what the effects of their investment decisions will be on communities and the climate. In doing so, many have shown that there does not need to be a trade-off between the impact that an investment can have and the financial return to the investor.

As a result of this rapid growth, however, the sustainable investment products on offer have proliferated, and this has made it difficult to assess which products are truly compliant with ESG requirements. The push by regulators across the world to create disclosure requirements will ensure that the growth in the ESG investment market is supported by robust evidence, and that investors can make decisions with confidence.

The quality of metrics used in ESG frameworks, along with the use of data from consistent and reliable sustainability-related financial disclosures, will be crucial in ensuring the maturity of the ESG investment market. Regulations like those announced by various national and international regulators, as well as private and non-governmental initiatives, will nurture investor confidence in these products, as well as ensuring that investment flows are targeted so as to achieve genuine environmental impacts. Discussions at COP26 stressed that both private and public finance will be pivotal in the green transition. If funds are to be mobilised on the scale and with the direction necessary, such regulations will be crucial.

1 Walker, O. and Hodgson, C. (2021), ‘Carney-led finance coalition has up to $130tn funding committed to hitting net zero’, Financial Times, 3 November.

2 Flood, C. (2021), ‘Regulators step up scrutiny over investment industry “greenwashing”’, Financial Times, 8 November.

3 Bloomberg (2021), ‘ESG assets may hit $53 trillion by 2025, a third of global AUM’, 23 February.

4 Impact Investing Institute (2021), ‘Pensions with Impact – Adopting a transitional mindset for a better future’, 3 November.

5 Financial Conduct Authority (2021), ‘Authorised ESG & Sustainable Investment Funds: improving quality and clarity’, 19 July.

6 European Commission, ‘Sustainability-related disclosure in the financial services sector’.

7 Financial Conduct Authority (2021), ‘DP21/4: Sustainability Disclosure Requirements and investment labels’, 3 November.

8 HM Treasury (2021), ‘Greening Finance: A Roadmap to sustainable Investing’, 18 October.

9 Financial Times (2021), ‘Regulators step up scrutiny over investment industry “greenwashing”’, 8 November.

10 IFRS Foundation (2021), ‘About the International Sustainability Standards Board’.

11 IFRS Foundation (2021), ‘IFRS Foundation announces International Sustainability Standards Board, consolidation with CDSB and VRF, and publication of prototype disclosure requirements’, 3 November; Value Reporting Foundation, ‘SASB Standards connect business and investors on the financial impacts of sustainability’.

12 Fish, A.J.M., Kim, D.H. and Venkatraman, S. (2019), ‘The ESG Sacrifice’, 17 November, pp. 1–2; Cornell, B. (2020) ‘ESG Preferences, Risk, and Return’, 5 November; Berg, F., Koelbel, J.F., Rigobon, R. (2019), ‘Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings’, 15 August.

13 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2021), ‘COP26 Finance Day Guide’, 1 November.

Related

The 2023 annual law on the market and competition: new developments for motorway concessions in Italy

With the 2023 annual law on the market and competition (Legge annuale per il mercato e la concorrenza 2023), the Italian government introduced several innovations across various sectors, including motorway concessions. Specifically, as regards the latter, the provisions reflect the objectives of greater transparency and competition when awarding motorway concessions,… Read More

Switching tracks: the regulatory implications of Great British Railways—part 2

In this two-part series, we delve into the regulatory implications of rail reform. This reform will bring significant changes to the industry’s structure, including the nationalisation of private passenger train operations and the creation of Great British Railways (GBR)—a vertically integrated body that will manage both track and operations for… Read More