When regulators innovate, does innovation prosper?

In the third of a series of articles about digital markets,1 we look at the potential impact of proposed digital regulation on innovation. The European Commission’s proposals for the Digital Markets Act (DMA) aim to promote innovation by making markets more contestable. Contestability is an important driver of innovation, but economics identifies that innovators also need to be able to appropriate the gains from their innovation. Policies that promote contestability can be detrimental to appropriability, and this trade-off does not appear to have been captured in the Commission’s proposals for the DMA.

The European Commission has now published its proposals and impact assessment for the Digital Markets Act (DMA).2 In this article, we examine whether the Commission is fully accounting for the possible trade-offs between its goal of increasing the contestability of digital markets and promoting innovation.

Innovation is crucial for the development of the European economy. For a developed economy, the key source of economic growth in output per worker over the long term is innovation. Policies that increase the incentive or ability of European firms to innovate will therefore increase the European economy’s growth potential over the long term, and vice versa.

In this article, we first outline the measures included in the DMA and the impact that they may have on firms’ incentives to innovate. Second, we consider whether firms outside the scope of the DMA might increase their innovation efforts sufficiently to compensate for any loss of innovation from firms within the DMA’s scope. Finally, we examine the potential trade-offs between the goals of promoting contestability and promoting innovation, and whether these have been fully accounted for in the Commission’s considerations around the DMA.

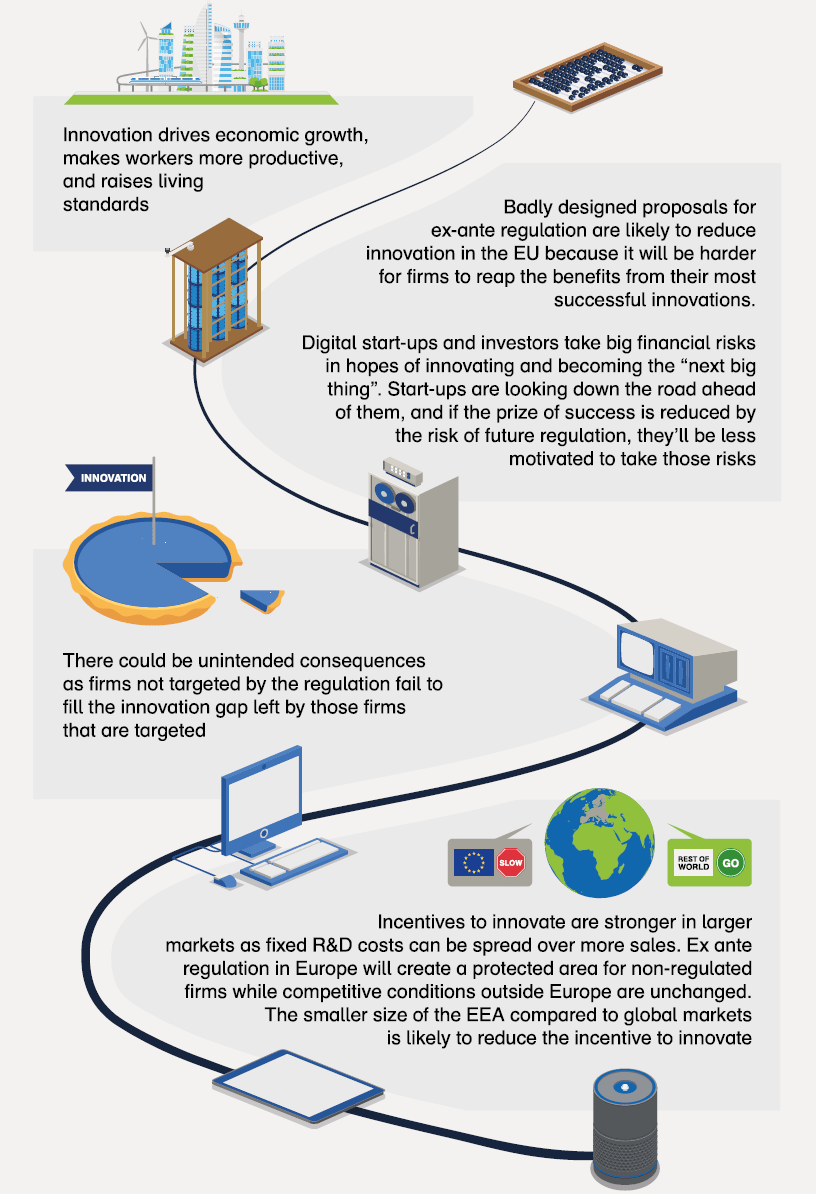

The discussion draws on research that Amazon commissioned from Oxera on the drivers and trade-offs for innovation.3 Some conclusions of this research are summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1 The impact of the Digital Markets Act on innovation

The DMA and innovation

In its current form, the Commission’s proposed DMA identifies platforms that have become large ‘gatekeepers’ and limits their conduct by imposing various obligations and prohibitions on them.

This is a departure from standard competition law, which is based on the principle that firms are permitted to grow (organically—i.e. not through mergers) as large as possible without consequences. In other words, it is not the development of earned market power that is perceived to be the problem; rather, it is the abuse of that market power in going beyond ‘competition on the merits’ to the detriment of the competitive process and consumers that is viewed as problematic.4

Defining gatekeepers

In order for a platform to be designated as being within the scope of the DMA, it must be a ‘gatekeeper’ provider of a ‘core platform service’. The core platform services include online intermediation services; online search engines; and online social network services, among others.5

A gatekeeper is a provider of a core platform service that:

- has significant impact on the internal market;6

- serves an important gateway for business users to reach end-users;7

- enjoys an entrenched and durable position.8

The quantitative thresholds associated with these definitions are effectively a set of rebuttable presumptions. A company that meets them can present arguments to the Commission as to why it qualitatively does not meet the definition of a gatekeeper in the environment in which it operates. Similarly, after an investigation, the Commission may designate a firm providing a core platform service as a gatekeeper even if it does not meet the quantitative thresholds, provided that the Commission considers that it does meet relevant qualitative thresholds. This gives the Commission substantial discretion in terms of choosing the platforms to which these regulations apply.

Obligations that could impede innovation

Among the prohibitions and obligations,9 there is a general prohibition on gatekeepers combining data from their core platform service with data from their other services, or requiring users to have accounts that are registered with other services of the gatekeeper.10 There is a further set of obligations concerning data-sharing and providing data to potential rivals either for free or on FRAND terms.11

One feature of the digital sector is that different business models compete with one another. For example, many firms offer email services; some monetise those email services through subscriptions or through data. Innovations that allow consumers to trade data for access to services at no monetary cost may cease to be profitable for platforms designated as gatekeepers if they are unable to combine the data from a new innovation with data from other sources, or if the data must be shared with potential rivals.12 The cost of this foregone innovation does not fall exclusively on the firm that would have provided it, but also on consumers who forego the benefits of such innovation.

Other prohibitions centre on governing gatekeepers’ relationships with their business users. The goal of these proposals is to rebalance the negotiating strength from ‘gatekeeper’ platforms towards business users and suppliers of services or products complementary to the core platform itself (‘complementors’). These include (among other measures):

- banning wide MFN clauses (which prevent suppliers from offering the same products on better terms through other sales channels);

- allowing business users to promote offers to and conclude contracts with end-users without necessarily using the core platform services for that purpose;

- banning platforms’ use of data generated by business users in competition with those business users;

- imposing restrictions on self-preferencing;

- giving access to third-party app stores;

- providing third parties with as much access to the operating system as the platform operator enjoys for the purpose of writing applications.13

Obligations designed to shift negotiation power away from gatekeeper platforms to business users and those supplying services that are complementary to the platform can also weaken platforms’ innovation incentives. Platforms create value by matching business users to end-users—innovations that improve that matching process increase the value of the platform, making it more useful for business users and end-users. However if the negotiating position of platforms is weakened with respect to business users, platforms may be able to capture less of the additional value generated by their matching innovations and so may have reduced incentives to innovate.

Innovation by non-designated platforms

If the Commission’s proposals reduce the incentives for innovation by designated platforms, this raises the question as to whether there might be a positive impact on innovation by firms that are not designated platforms. The DMA may have a positive impact on the innovation incentives of potential rivals to platforms that the Commission has designated as large gatekeepers. Forcing designated gatekeepers to share their data or imposing limits on how that data may be used may make it easier for rivals to reach the critical number of customers to be viable. This would tend to increase incentives for innovation from smaller firms.

However, there may also be negative impacts on innovation incentives. There are some important reasons why we might not expect any additional innovation to compensate for lost innovation by designated gatekeepers. Indeed, innovation by smaller firms may actually fall.

First, the big prize from innovation that innovators and investors are aiming for is that their innovation is so successful that it will help them become large firms. They want to be ‘the next big thing’. However, if such success results in being designated as within the scope of the DMA and the associated restrictions, then the value of becoming the next big thing is likely to fall. Innovators and their investors’ incentives may be weakened as the size of the prize is materially reduced if they are within the scope of the DMA.14 A similar point was made by Segal and Whinston, economists at Stanford and Northwestern University, in their 2007 article in the American Economic Review.15 This is why the position of competition law has been that there is no problem with firms becoming large, or even dominant (organically), provided that there is no abuse of that dominant market position.

Second, where innovation is a dimension of competition, if one firm cuts back on its R&D efforts, there is not a clear incentive for rivals to increase their own efforts sufficiently to compensate. Indeed, an expectation that this will not happen has been the reasoning behind past Commission decisions to make merger clearance subject to remedies requiring divestment of R&D facilities and resources.16

The trade-offs

When considering intervening in markets to improve outcomes, there are often trade-offs that have to be made. When looking at incentives to innovative, the economics literature identifies such a trade-off between appropriability and contestability.17 This trade-off has been at the heart of debates around IP and copyright for many years.

The drivers of innovation

The drivers of innovation by firms can be categorised into two groups:18

- appropriability—the ability of an innovator to extract some value from their innovation and recoup the R&D investments that led to the innovation;

- contestability—the ability to attract sales from rivals by offering consumers a higher-quality or lower-priced product.

Both of these factors are important when a firm considers an R&D investment that might lead to some innovation. If there is no way for a firm to protect its innovation from imitation by rivals, then successful innovation will not differentiate the firm from its rivals, reducing the overall incentive to innovate. This is why intellectual property law grants an innovator temporary monopoly rights over its innovation. There is a cost in terms of foregoing the benefits of static competition, but it is potentially outweighed by greater dynamic competition through innovation.

Similarly, if the market in which an innovation might be launched is genuinely incontestable, then improvements in the quality or value of an innovator’s product would not matter—customers still would not switch. This would also lead to reduced incentives for innovation.

The Commission’s proposals make much of their promotion of contestability, but there is no mention of the potential impact on appropriability.

Even if the innovator is not overly motivated by financial concerns and appropriability, and is more concerned with proving that its concept works or solves a problem, appropriability will still matter to those investing in the project. Without investors, innovators will struggle more to bring their innovations to the market.

The trade-off

It may be true that the Commission’s DMA proposals could improve the contestability of digital markets—this will depend on the extent to which the practices prohibited by the DMA are indeed harmful, and on the unintended consequences that they have on market dynamics. However, the proposals may also reduce the ability of innovators and investors to appropriate some of the value of their innovations if successful. This is also a bad signal for the appropriability of future innovations by future innovators (as discussed above). This is an issue that competition law has grappled with over the years, in terms of the impact of over- or underenforcement on dynamic efficiency.

This important trade-off does not appear to be considered by the Commission in its proposals or the associated impact assessment. For example, in the impact assessment documents, the word ‘innovation’ was used 131 times; the words ‘contestable’ or ‘contestability’ were used 133 times; and the words ‘appropriable’ or ‘appropriability’ were not used.19 Indeed, the Commission describes the main cost of their proposals as being the compliance costs for the designated firms.20 There does not appear to be any consideration of how the regulations might affect the strategic choices of designated firms, or of firms that might distort their strategic choices to avoid designation.

Trade-offs are key

There are important trade-offs between the objectives of securing better market outcomes for consumers today and the incentives to innovate that will provide consumers with better and cheaper products tomorrow. This trade-off has been important in the development of competition and intellectual property policy as they have evolved to trade off dynamic and static efficiency. This is why, for example, it is not an offence in competition law to become a dominant firm, but it is an offence to abuse that dominant position.

The development of good regulation should consider these trade-offs, otherwise market approaches to investment and technology are likely to respond in ways that the regulator did not intend, leading to suboptimal outcomes. These trade-offs do not seem to have been explicitly considered in the Commission’s proposals and impact assessments around the DMA.

Designing regulation to correct market failures and improve outcomes in digital markets is a challenge that governments around the world are facing. Grappling with the trade-off between contestability and appropriability, as has been done in intellectual property, is key to unlocking the benefits of innovation in technology. To achieve this balance, the Commission could consider both applying some of the regulations only when there is evidence that it will improve outcomes, and allowing successful firms defined grace periods to recover their investment before regulations are applied.

1 The first two articles in the series are: Oxera (2021), ‘If data is so valuable how much should you pay to access it?’, Today’s Agenda, February; and Oxera (2021), ‘Move fast and analyse things: sensible regulation for digital markets’, Today’s Agenda, January.

2 See European Commission (2020), ‘Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on contestable and fair markets in the digital sector (Digital Markets Act) COM/2020/842 final’.

3 See Oxera (2020), ‘The Impact of the Digital Markets Act on innovation’, November.

4 See Tirole, J. (2015), ‘Market Failures and Public Policy’, American Economic Review, 105:6, pp. 1665–82. See in particular p. 1670.

5 The ‘others’ include: video sharing platforms; number-independent interpersonal communication services; operating systems; cloud computing services; and advertising services, including ad networks or any other intermediation service.

6 Presumed by the Commission to be the case when annual EEA turnover has been at least €6.5bn in the last three financial years, or where market capitalisation or equivalent fair market value was at least €65bn in the last financial year, and the firm provides a core platform service in at least three member states.

7 Presumed by the Commission to be the case when there are more than 45m active monthly end-users in the EU and more than 10,000 yearly active business users in the EU in the last financial year.

8 Presumed by the Commission to be the case when the second condition has been met for the previous three financial years.

9 Note that the Commission draws a distinction between prohibitions or obligations that are listed under Article 5 and those listed under Article 6. The former will be applied and the latter are ‘susceptible of being further specified’, meaning that it is still open to discussion whether the Article 6 obligations and prohibitions will apply in their current form. For the purposes of this article, we ignore that distinction and merely consider the effects of all obligations and prohibitions whether listed under Article 5 or 6.

10 See in particular Article 5(a), (e), and (f).

11 See Article 5(g), and Article 6(g), (h), (i), and (j). To provide data on ‘FRAND terms’ is to charge Fair, Reasonable And Non-Discriminatory access prices.

12 In terms of the value of combining data from different sources, see Baldwin, Y. C. and Woodard, C. J. (2009), ‘The Architecture of Platforms: A Unified View’, in A. Gawer (ed.), Platforms, Markets and Innovation, Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 19–44.

13 See Article 5(b), (c), and Article 6(a), (d), (c), and (f).

14 It is not just the obligations that produce such unintended consequences. As one participant at a roundtable discussion organised by Oxera on the DMA proposals suggested, the rules surrounding designation itself could also have unintended consequences. Specifically, the criteria saying that a firm is presumed to have an impact on the internal market if, among other things, it is active in at least three member states might lead firms to delay rolling out their offerings across more than two member states as a way of delaying designation as a gatekeeper.

15 See Segal, I. and Whinston, M. D. (2007), ‘Antitrust in innovative industries’, American Economic Review, 97:5, pp. 1703–30.

16 See, in particular, Case M.7932 – Dow/Dupont and Case M.8084 – Bayer/Monsanto.

17 See Segal, I. and Whinston, M. D. (2007), ‘Antitrust in innovative industries’, American Economic Review, 97:5, pp. 1703–30.

18 See Shapiro, C. (2012), ‘Competition and innovation: Did Arrow hit the Bull’s Eye?’, in J. Lerner and S. Stern (eds.), The Rate and Direction of Inventive Activity Revisited, University of Chicago Press, pp. 361–410. Shapiro highlights a third consideration of ‘efficiencies’ that is relevant to the analysis of mergers.

19 European Commission (2020), ‘COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF THE IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT Accompanying the document Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on contestable and fair markets in the digital sector (Digital Markets Act)’.

The stated word counts apply to parts 1 and 2 of the document.

20 See European Commission (2020), ‘Proposal for a Regulation Of The European Parliament And Of The Council on contestable and fair markets in the digital sector (Digital Markets Act)’, p. 10.

Download

Related

Investing in distribution: ED3 and beyond

The National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) has published its vision for the UK’s electricity distribution network. Below, we review this in the context of Ofgem’s consultation on RIIO-ED31 and its published responses. One of the policy priorities is to ensure that the distribution network is strategically reinforced in preparation… Read More

Leveraged buyouts: a smart strategy or a risky gamble?

The second episode in the Top of the Agenda series on private equity demystifies leveraged buyouts (LBOs); a widely used yet controversial private equity strategy. While LBOs can offer the potential for substantial returns by using debt to finance acquisitions, they also come with significant risks such as excessive debt… Read More