Why vertical restraints? New evidence from a business survey

Vertical restraints refer to agreements or contract terms between firms that are in different layers of the supply chain—for example, an agreement between a manufacturer and a retailer or distributor. These can include restrictions on the overall number or type of retailers selling a particular product; on the geographic area where each retailer can sell; whether they can sell competitor products; and/or the price at which retailers may sell the products. The box below shows the types of vertical restraint that businesses often use.

Common vertical restraints

In practice, businesses can use a wide range of vertical restraints, including:

• selective distribution: the number of distributors/retailers through which a particular product is sold is restricted by the supplier;

• exclusive distribution: a supplier sells its products to only one distributor in a given territory;

• exclusive supply: a supplier is obliged or induced to sell its products to only one buyer;

• single branding: a retailer is obliged or induced to source its products from only one manufacturer/supplier;

• quantity forcing: the buyer is obliged or otherwise incentivised by a supplier to source most of its products from that one supplier.

In addition, some businesses may use restraints regarding the level of the retail price. One such restraint is resale price maintenance (RPM), where a manufacturer sets a fixed or minimum resale price that the retailer can charge. Under EU competition law, RPM is presumed to be illegal. Manufacturers may also recommend a retail price to the retailer (the recommended retail price, RRP). Although the specification of an RRP by a manufacturer is, by itself, not a restraint, forcing retailers to price at the RRP could amount to RPM.

Businesses also use most-favoured-nation (MFN) (or ‘parity) clauses regarding prices and other terms. These contractual provisions between a specific buyer and a specific seller of a product or service stipulate that the seller will offer its product or service to the buyer on terms that are as good as the best terms offered to other buyers. As such, the debate about when certain vertical restraints have anticompetitive effects, and when they might be beneficial for the consumer, is not new. There is a large and well-established body of economics literature highlighting the mechanisms by which vertical restraints may have anti- and/or pro-competitive effects. However, the growth of the Internet and, with it, e-commerce, has revived this debate among competition authorities, practitioners and academics.

For example, the European Commission, as part of its Digital Single Market strategy, has launched an inquiry into e-commerce, which will focus on ‘potential barriers erected by companies to cross-border online trade in goods and services’.1 It is also investigating a number of businesses (such as Amazon, Sky UK and six major Hollywood film studios) in relation to specific vertical restraints.2 National competition authorities have also been active in investigating vertical restraints in many markets. The most salient example is the online hotel booking market, which has been investigated by the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), the German Bundeskartellamt, and at least eight other authorities. There have also been inquiries into online retailing of running shoes in Germany (for example, into the practice by ASICS of banning the use of online marketplaces), mobility scooters in the UK (where the concern was also about online sales bans), and consumer electronics across Europe.

In this context, the Oxera report, prepared in collaboration with market research firm, Accent, presents much-needed primary evidence on why businesses use vertical restraints (including any anti- and pro-competitive reasons). It also looks at the impact on market players and consumers, and how this has been influenced by e-commerce, in order to inform the assessment of when potential benefits from these restraints may outweigh the potential consumer harm.3 Before discussing these survey results in more detail, it is worth exploring what the economic literature says on the impact of vertical restraints.

What are the insights from the economic literature?

There is a large body of literature exploring the harmful and beneficial effects of vertical restraints, including studies that assess how the Internet and e-commerce may affect the balance between anti- and pro-competitive effects.

On the anticompetitive front, economists note that vertical restraints can:4

- soften intra-brand competition—for example, by reducing the number of retailers that stock a given brand;

- soften inter-brand competition—for example, by restricting a retailer from stocking a competing brand;

- facilitate collusion—for example, through price agreements, such as RPM, that can aid collusion by facilitating monitoring and enforcement.

The literature suggests that vertical restraints that reduce intra-brand competition (i.e. competition between retailers selling the same product supplied by the same manufacturer) are less harmful for consumers if inter-brand competition (i.e. competition among manufacturers) is strong.

Pro-competitive reasons discussed in the literature include the following.

- Addressing vertical and horizontal externalities—in particular, manufacturers may use restraints such as selective or exclusive distribution (i.e. limiting the number of retailers) to ensure that retailers earn sufficient margins and therefore have the appropriate incentives to stock the product, and provide pre- and/or after-sales service to consumers on behalf of the manufacturer. Such restraints can also prevent other retailers from ‘free-riding’ on one retailer’s efforts to provide customer service (such as product information) and to remove double marginalisation.5

- Reducing transaction costs—for example, quantity forcing may reduce the number of trading partners and the costs incurred for associated negotiations; or RRPs may help manufacturers to convey information about market conditions, such as demand trends, to uninformed retailers.6

- Signalling the high quality of a product—this might include a direct signal through the level of the RRP and/or an indirect signal by restricting the distribution network to retailers with a reputation for quality, such that the fact that the retailer is stocking a product signals pre-selection of high-quality products for consumers.7

- Signalling a status good—branded-goods manufacturers may use selective distribution to limit usage and maintain a high price when they want to target a group of high-income consumers who derive a higher benefit from the ‘social status’ of using an expensive and/or exclusive product.8

The literature also indicates that the Internet is likely to influence these reasons due to the opportunities and challenges that it presents to businesses. For example, the Internet has reduced search costs for consumers and increased transparency for both consumers and suppliers; created a direct route to market; and increased the potential geographic reach and scope of both manufacturers and retailers. With greater opportunities for some market participants on the one hand, it has put businesses under more pressure on the other, which is likely to strengthen some of the justifications reported above.

Evidence on business rationale and impact of e-commerce

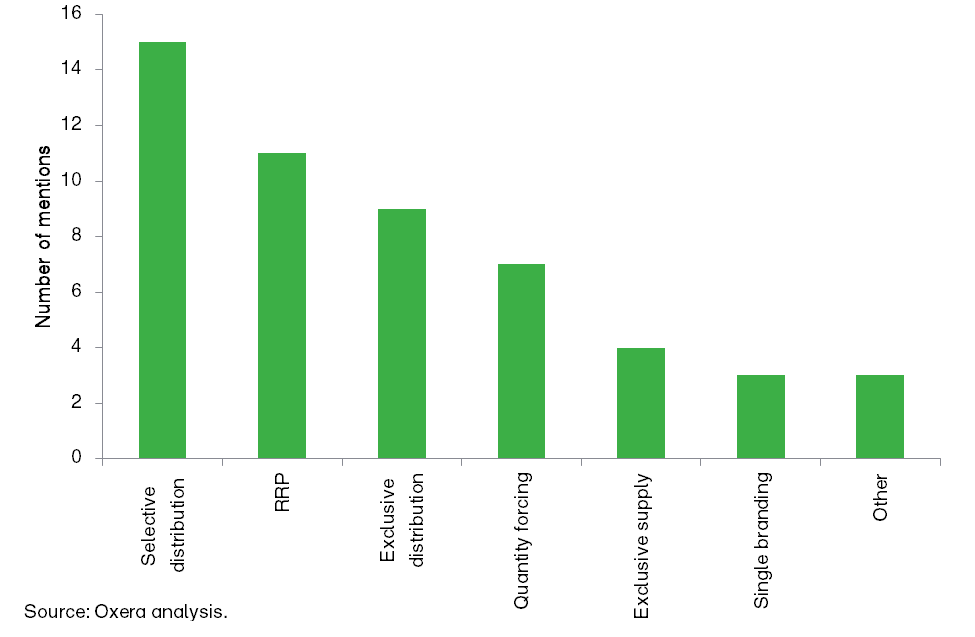

To explore these issues in more detail, telephone interviews with 33 small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs) were conducted as part of the Oxera study. The survey sought to test the above reasons, and whether they varied across markets. We also explored the impact of e-commerce on the use of vertical restraints and on different market participants and consumers. Participants included retailers and manufacturers, some of which were selling high-end brands, technical products, and products with some form of pre- and/or after-sales service. Figure 1 shows the practices they use.

Figure 1 Types of vertical restraint and related practices

There was variation in the way in which RRPs were used. Some manufacturers merely specified an RRP, while others took active measures to ensure that the retailers priced at or close to the RRP.

So, why do businesses use vertical restraints? Consistent with the economic literature, the most common reasons stated by participants in the survey were to prevent free-riding and thereby maintain pre- and after-sales service quality, and to protect brand image.

Other stated reasons (for example, for using quantity forcing or single branding) included increasing brand presence in stores, cementing the viability of the business relationship, and ensuring that the retailer had the necessary expertise. However, some responses also suggested that manufacturers and retailers use these practices only to secure a good commercial deal, without a clear link to any (actual or perceived) benefit to consumers. The two most common reasons stated are discussed below.

Preventing free-riding and promoting quality

Many of the participants using selective or exclusive distribution, and specifying RRPs, highlighted that the main rationale was to prevent free-riding and ensure quality of service. As also highlighted in the economics literature, this was particularly important for products requiring some form of customer service—either before or after the sale (such as advice on the quality of products or demonstration of use). Examples included high-end machines that require technical advice, a prescription product where personalised advice was necessary, bespoke bicycles that may require after-sales customer service, and special adult shoes that require expertise and training in shoe-fitting:9

If [retailers are] taking the time to fit the [product], to add the value…etc. then it seems only fair that you are long term rewarded for that effort and therefore they come back and buy the products from you. What we don’t want to have is a company whose…you know, they do all the work and then some Internet reseller nicks all the business.

if the consumer is wishing to invest in a premium product they want to be able to see it…and someone who has got competent knowledge to explain the product to them, so we [retailer] are able to ensure that they make the right decision.

As for the impact of vertical restraints, the responses highlight that, while they necessarily restrict the number of retailers and availability, and potentially increase prices in the short run, in the longer term such restraints help to increase retail service standards, maintain stock in stores, and improve the customer experience. This is particularly relevant in recent years, given the higher scope for free-riding by online businesses. For example, one retailer explained how the pressure from lower prices online may lead smaller stores to no longer stock the product:

[The manufacturer] had a bit of an issue with it being sold into both online and retail, you know, sort of bricks and mortar environment, and there was a big issue with retailers like myself not being able to take the product because it was being discounted heavily online.

then it would mean that potentially you wouldn’t find them on the high street because we [the retailer] wouldn’t be able to support the price.

The box below shows how vertical restraints can help to maintain product quality and protect retailers’ incentives to provide a pre-sales service for complex products.

Case study: a manufacturer of a custom-made prescription product

This manufacturer uses mainly independent bricks-and-mortar retailers, and has a stated policy of not supplying Internet resellers, for two reasons:

• to ensure safety and quality for the consumer, given the complexity of the prescription: ‘it would be very unhealthy and risky for a patient to try and access our product without going through a [specialised retailer]’

• to prevent Internet resellers from free-riding on the efforts of the retailer in providing the product and service: ‘What we don’t want to have is a company…[that] do all the work and then some Internet reseller nicks all the business.’ In selecting retailers, the manufacturer has a preference for smaller firms, stating that they seek retailers who would ‘]sync with [their] values, that are looking to elevate [the service], have more experience with their patient, are really committed to…to do something a little bit…a little bit more than just the average [retailer] will do.’

The selection criterion also appears to help smaller retailers to compete effectively with larger ones, as they can ‘differentiate themselves as well from the likes of the Internet, and the bigger…the bigger, bigger volume chains and therefore they could more have an emphasis on quality, more of an emphasis on an experience and adding value to the patient’.

The manufacturer also suggests that there has been a reduction in quality of service in the broader mass market (i.e. as opposed to custom-made products) due to commoditisation following the growth of online sales and the consequent downward pressure of price. This is because ‘in an effort to try and protect and say, you know, any margin that they can, [retailers] reduce the amount of time they spend, reduce the effort they spend, don’t add as much value to the patient’.

Source: Oxera survey.

Protecting brand image

Protecting the brand image was also viewed as important by respondents. As explained by participants, this reason can in turn be linked to two separate reasons highlighted in the literature:

- to signal the actual or perceived high quality of the product and/or service to the customer;

- to maintain the image of the product as a status good for consumers (particularly for luxury brands).

This was often achieved by using selective distribution systems based on the reputation or brand of the retailer, as well as by specifying an RRP (although the responses suggest that the retailers did not always price at the relevant RRP, albeit some were influenced by the RRP and the pressure from some manufacturers to price at the RRP):

you got your upmarket shops and your downmarket shops I suppose, you know it would want to be in the right place.

it’s more about being seen in the best stores, you know, it’s being seen with the best partners, being seen in the best malls, you know, that brand.

Interestingly, although selective distribution would be expected to reduce intra-brand competition, one response showed that there could be an increase in inter-brand competition due to adjacent positioning of competing brands within a specific retailer:

the job is really you always want to set up next to the best and like minded brands. If we have a choice we would sit alongside [Brand 1, 2 and 3].

In general, while some participants mentioned that the Internet had helped their business by making it easy to find business partners and reach customers, the responses generally suggest that the rise of e-commerce has made it more difficult for manufacturers to ensure that the brand image and quality perception are maintained, and that this often dissuades them from selling through online platforms.

Concluding remarks

The insights from the interviews confirm much of the understanding from the economics literature on the costs and benefits to consumers of vertical restraints. Indeed, the strength of any pro-competitive rationale would be expected to vary across markets. However, the need for SMEs to have vertical restraints in place, in order to offer widespread availability and quality service to consumers, seems to have increased with the ever-growing challenges posed by e-commerce.

Therefore, while there are legitimate concerns about some of these agreements, this study highlights a need for caution when analysing the impact of certain vertical restraints, including a need to account for both the short- and long-term impacts on consumers.

Download

Contact

Dr Avantika Chowdhury

PartnerRelated

- Energy

- Financial Services

- Pharmaceuticals and Life Sciences

- Telecoms, Media and Technology

- Transport

- Water

Download

Related

Future of rail: how to shape a resilient and responsive Great British Railways

Great Britain’s railway is at a critical juncture, facing unprecedented pressures arising from changing travel patterns, ageing infrastructure, and ongoing financial strain. These challenges, exacerbated by the impacts of the pandemic and the imperative to achieve net zero, underscore the need for comprehensive and forward-looking reform. The UK government has proposed… Read More

Investing in distribution: ED3 and beyond

In the first quarter of this year the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC)1 published its vision for the UK’s electricity distribution network. Below, we review this in the context of Ofgem’s consultation on RIIO-ED32 and its published responses. One of the policy priorities is to ensure… Read More