Women and work: the impact of childcare support

In April 2024, the UK government will roll out the first phase of its new childcare funding programme, as announced in the Chancellor’s Spring Budget 2023. Official estimates may be understating the expected beneficial effects, underplaying the likely responsiveness of women to this support in terms of increased participation and hours worked. Furthermore, evidence from Canada suggests these policies can have far-reaching positive effects on women’s work-related choices. Therefore, careful implementation and appropriate attention must be given to this policy to ensure that the UK is able to benefit from all of its potential impacts.

The first phase of the government’s new childcare funding programme extends 15 hours of free childcare to all children aged two or older. When the rollout is complete in September 2025, all children under the age of five will be entitled to 30 hours of free childcare per week if each parent earns less than £100,000, but more than £167/week. Previously, parents could only receive the 30 hours of free childcare the term after their child turned three.

The effects of this policy should not be understated. It has the potential to increase mothers’ participation in the labour force, reduce the gender wage gap, increase the fertility rate and economic productivity, addressing some of the issues constraining the UK’s economic growth in the longer term. Official estimates may be understating the expected beneficial effects, underplaying the likely responsiveness of women to this support in terms of increased participation and hours worked. Furthermore, the broader long-term benefits may not have been factored in. Therefore, careful implementation and appropriate attention must be given to this policy to ensure that the UK is able to benefit from all of its potential impacts.

A seismic change in policy direction with real-world implications

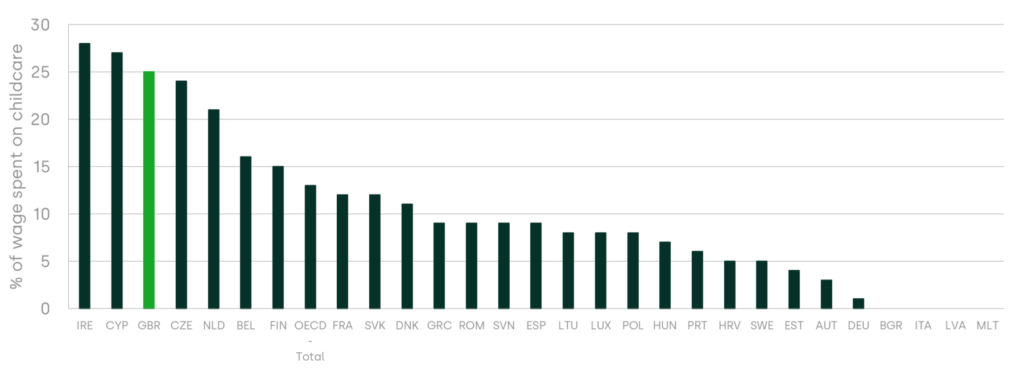

This is a seismic change in policy direction, given that the UK faces some of the highest childcare costs in the OECD net of government supports. For couples earning an average wage, net childcare costs account for 25% of their earnings in the UK, as shown in the figure below.1

Figure 1.1 Net childcare costs for a couple earning an average wage, as a percentage of wage

Source: Oxera analysis of OECD data.

What does this mean practically? A parent who re-joined employment when their child was one year old, for example, would have paid out of pocket for nursery fees during this two-year period. Fees for one child attending nursery full-time (50 hours a week) are on average £270 a week in Great Britain, which translates to £14,000 annually, or £28,000 over this two-year period (without factoring in any additional government support such as Tax-Free Childcare). This means that the new 30-hours-free-childcare policy would save a family in this situation roughly £17,000 over this two-year period. This is a significant amount for most families in the UK, given that the median household disposable income in 2022 was £32,300.2 For middle- and lower-income parents, that £17,000 is the difference between one parent (usually the mother3) staying at home or re-entering the labour market.

The significance of this cost to a family can also mean that many couples delay or choose not to have children due to the cost of childcare alone. Consider the following survey findings.

- A recent survey of 1,000 parents with children under four found that 63% would delay having or not have another child due to high childcare costs.4

- A 2022 survey conducted by charity Pregnant Then Screwed and Mumsnet of 27,000 parents found that ‘two-thirds of respondents…said they were paying as much or more for their childcare than for their rent or mortgage.’ [emphasis added]5

- Another survey conducted by Pregnant Then Screwed found that of those who had had an abortion in the last five years, 60.5% said that the cost of childcare influenced their decision and 17.4% said that it was the main reason they chose to have an abortion.6

By alleviating the significant cost of childcare, this policy may have a positive impact on birth rates beyond the five-year horizon considered in the OBR’s outlook. The economic impact of an increase in the fertility rate over the long run is self-explanatory—more babies means more future workers.

In its November 2023 economic and fiscal outlook, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) states that ‘we anticipate a fall in inactivity due to caring responsibilities as recent drops in birth rates mean that the share of children in the population is set to fall in the medium term.’7

While this general birth rate decline is broadly aligned with the rest of the developed world, if the survey results reported above reflect attitudes more broadly across the UK, by alleviating the significant cost of childcare, this policy may have a positive impact on birth rates beyond the five-year horizon considered in the OBR’s outlook.

Conservative estimates of labour market entry by the OBR

The OBR estimates that this will result in 60,000 workers entering the labour market by 2027–28, working an average of approximately 16 hours per week (average of part-time workers). The OBR also estimates that approximately 1.5m mothers of very young children who are already formally employed will increase the hours they work outside of the home (albeit by less than 16 hours per week).8

Yet there are many reasons to believe that the OBR’s outlook may be understating the potential benefits of this policy change. First, the OBR itself notes that there is uncertainty around how responsive parental employment will be to the childcare provisions. Thus, the labour market decisions of parents may be more or less responsive to the new provisions than expected.

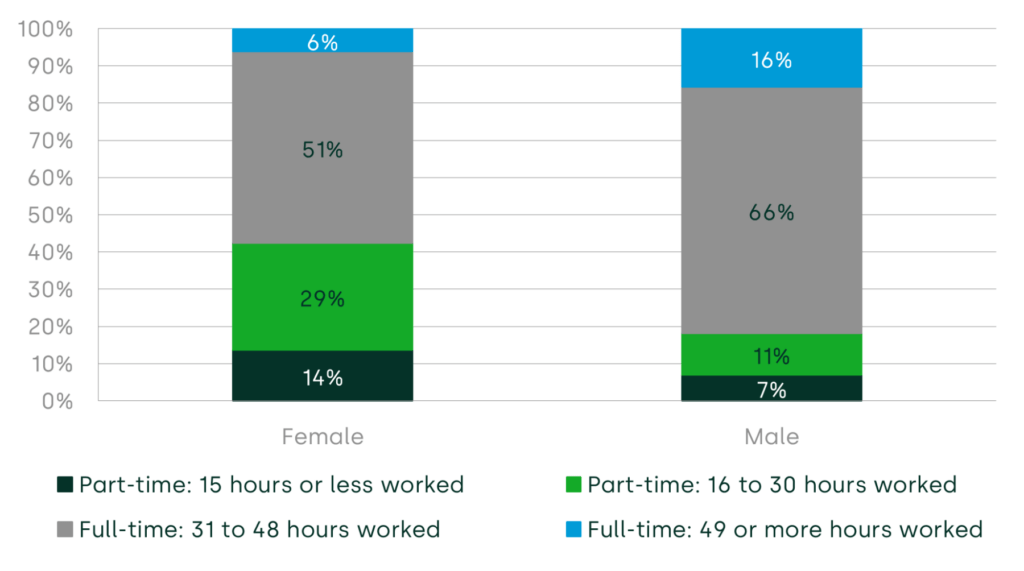

Moreover, women are almost twice as likely as men to work part-time, and most part-time work is between 16 and 30 hours a week. It appears that the OBR’s 16-hours estimate is based on the lower bound of a part-time worker. However, as shown in Figure 1.2 below, 57% of women on average work 31 or more hours a week, compared with 82% of men. In fact, after childbirth, the number of hours of work for women in paid employment falls from 40 hours to between 25 and 30 hours a week on average.9 Based on this data, it is reasonable to conclude that by using 16 hours a week as a benchmark, the OBR is underestimating the total hours worked by parents entering employment due to this policy initiative by almost a half.

By definition the OBR’s outlook is limited—focused on the next five years—and it would therefore not consider these long-term impacts. However, a policy change of this magnitude and with this level of potential socioeconomic and equality implications is likely to realise its full impact in the longer term.10

Figure 1.2 Hours worked by sex

After childbirth, the number of hours of work for women in paid employment falls from 40 hours to between 25 and 30 hours a week on average. It is therefore reasonable to conclude that by using 16 hours a week as a benchmark, the OBR is underestimating the total hours worked by parents entering employment due to this policy initiative by almost a half.

It is of course possible that those who remain in paid work following childbirth are a different cohort to those who left paid work following childbirth and are re-entering due to the childcare provision. As this policy has not yet taken effect in the UK, the progress of this should be closely followed to see if material differences do exist between these two groups.

International experience

This is where international comparators become key. The province of Quebec in Canada has been running a subsidised day-care programme for two decades and provides a model on which many other countries have based their universal subsidised childcare initiatives.11

The evidence from Quebec’s experience is striking in terms of its impact on the employment rate of women of ‘core working age’ as well as on the fertility rate.

First, while the employment rate of women with children under five years of age was comparable before the introduction of the policy in 1998, after its introduction, the employment rate for this cohort was 8 percentage points higher in Quebec—79% in 2014—compared to 71% in all other provinces in Canada. Moreover, the employment rate for women in Quebec has remained consistently higher than all other provinces since the introduction of subsidised day care.12 Subsequent research has demonstrated the causal link in this observation, and concluded that mothers who use childcare support (particularly middle- and low-income mothers) before their child is of school age are likely to remain in work later, once the child begins schooling.13

In addition, a comparison of the provinces of Quebec and Ontario demonstrated that the total fertility rate was higher in Quebec starting in 2004 (approximately five years after subsidised childcare was introduced), after four decades of similarity in fertility rates between the two provinces. This difference was not explained by differences in the composition of the population (i.e. more women of childbearing age in Quebec) or the divergent trends in labour force participation. In fact, the fertility rates of women aged 15 to 44 in Quebec increased alongside their labour force participation rate.14

The economic impact of an increase in the fertility rate over the long run is self-explanatory—more babies means more future workers.

The rest of the country has followed suit, with the Canadian federal government recently introducing a programme to dramatically cut day-care fees to $10 a day by 2026. There are early indications of an increase in female labour force participation in response to the first phase of this programme which has seen day-care costs cut in half across the country. The labour force participation rate of women aged 25–54 (considered the ‘core working age’) reached a record high of 85.1% in November 2022.15 This was also evidenced in a record-high employment rate for women in this cohort of 81.6%, compared to a steady rate of between 79.5% and 79.9% pre-pandemic.16

What the Quebec case study demonstrates is that there are many long-term impacts and a fundamental change in decision making by parents of young children, particularly mothers.

Research also finds that maternal employment has positive outcomes for sons and daughters when they are adults. Daughters of mothers who work outside the home are more likely to work outside the home themselves as adults, and in higher-paid and managerial work. While the employment rate for sons is not affected by maternal employment, there is evidence that sons of mothers who work outside the home spend more time on caring responsibilities than men whose mothers did not work in formal employment.17

The potential impact of this childcare policy is that not only will it increase women’s labour force participation in the medium run, it is likely to stay higher in the longer term as successive generations of women raised by mothers in paid employment are more likely to be in paid employment as well.

Impact on the gender wage gap

It is also possible that there will be impacts on the gender wage gap, which the OBR’s public documents do not seem to consider.

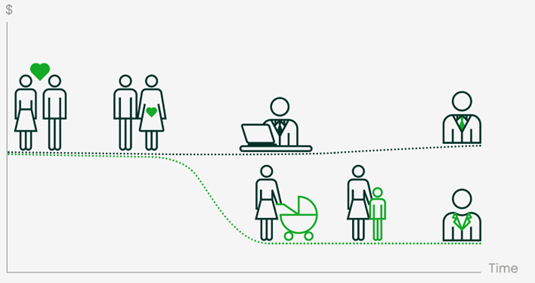

Through her Nobel-Prize-winning research, American economic historian Claudia Goldin has demonstrated how childcare decisions in a family have a direct impact on the gender wage gap. In particular, ‘the bulk of this earnings difference is now between men and women in the same occupation, and that it largely arises with the birth of the first child.’ [emphasis added]18 Put simply, women make different decisions due to often disproportionately bearing the weight of childcare.

Figure 1.3 The impact of parenthood on the earnings of men and women

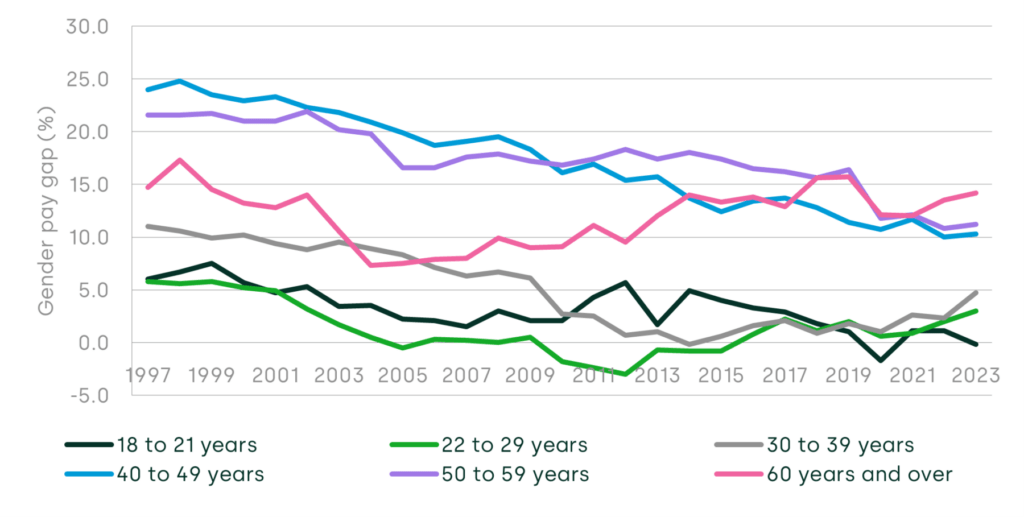

It is no secret that women more often choose careers that afford more flexible work, and are more likely to work part-time, as discussed above.19 These decisions send them down different career paths, which may limit their ability to realise the same lifetime earnings as their male counterparts. This is reflected in the data (see Figure 1.4 below), which shows that while the pay gap for full-time employees has been declining overall over time, the pay gap for those aged 40 or above has been consistently greater than for younger employees. In addition, fewer women in their 40s and 50s are in senior roles (e.g. manager, director, senior officials) when pay for these occupations typically increases at this time in a person’s career.20

Figure 1.4 21Gender pay gap for full-time median gross hourly earnings (excluding overtime), by age group, UK, April 1997 to 2023

By making childcare more affordable, this policy has the potential effect of reducing the differences in career decision making between men and women. In other words, if women have more affordable childcare options, they may make different career decisions that lead them down career paths where they are able to earn more, thereby reducing the gender pay gap. This has the potential to positively affect labour productivity—where labour productivity in economic terms refers to total output (measured in GDP) per hour worked.

Why does this matter?

In summary, this policy has significant potential to have a positive impact on the UK’s economy, which may not be fully reflected in the conservative estimates put forward by the OBR to date.

First, as illustrated above, there is the potential for it to lead to more hours worked than the 16 hours assumed by the OBR for new labour market entrants due to this policy, given employment patterns among working parents (and mothers in particular) borne out in the statistics. This is likely to lead to a greater net economic benefit than has been estimated by the OBR.

There is also the strong possibility that demand elasticity for parents is higher than expected, as shown in the Quebec example, and thus more parents will take up the policy than the 60,000 estimated by the OBR. This is subject to parents’ responsiveness to the policy. Yet if the experience in Quebec and, more recently, in the rest of Canada is any indication, there is likely to be a positive medium- and long-run impact on the employment rate. Thus, take-up of this policy may be higher than anticipated by the OBR.

Finally, there is the very real possibility that by reducing childcare costs, there could be a positive impact on the gender wage gap, since the policy has the potential to provide a more level playing field for career decision making for men and women after having children. In doing so, it will allow the labour market to clear at a more resource-efficient level, filling gaps in employment where they are needed. In other words, it has the potential to allow for better matching between people and jobs in society, analogous to Oxera’s research findings about the relationship between social mobility and job matching. In other words, better job matching occurs when a job can be filled by someone with the highest level of potential to perform well in that job rather than by someone who may be less well suited but, for example, less encumbered by childcare arrangements. This, in turn, means that the average productivity of a job should increase as employees are, on average, better suited to the job they are doing.22

In a period of sluggish productivity growth, and with an ageing population, there is a real opportunity for this policy to make a measurable difference in addressing some of the issues constraining the UK’s economic growth. The success of this policy now hinges on its execution.

1 OECD (2024), ‘Net childcare costs (indicator)‘, last accessed on 5 March 2024.

2 Office for National Statistics (2023), ‘Average household income, UK: financial year ending 2022’.

3 Fawcett Society (2023), ‘Paths to Parenthood: Uplifting New Mothers at work’, November, last accessed 28 February 2024.

4 Priestly, I., (2023), ‘Parents plan to have less children due to spiralling childcare costs’, National Day Nurseries Association, March, last accessed 5 March 2024.

5 Pregnant Then Screwed (2022), ‘1 in 4 parents have had to cut down on heat, food & clothing to pay for childcare’, press release, 25 March, last accessed 5 March 2024.

6 Pregnant Then Screwed (2022), ‘6 in 10 women who have had an abortion claim childcare costs influenced their decision’, press release, 8 July, last accessed 29 February 2024.

7 Office for Budget Responsibility (2023), ‘Economic and Fiscal Outlook November 2023’, para. 2.31.

8 Office for Budget Responsibility (2023), Economic and Fiscal Outlook March 2023, Chapter 4, p. 21.

9 Institute for Fiscal Studies (2021), ‘The careers and time use of mothers and fathers’.

10 Doepke, M., Hannusch, A., Kindermann, F. and Tertilt, M. (2022), ‘The New Economics of Fertility’, IMF, July, last accessed 29 February 2024.

11 Bloomberg (2018), ‘The Global Legacy of Quebec’s Subsidized Child Daycare’, December, last accessed 29 February 2024.

12 Fortin, P. (2017), ‘What Have Been the Effects of Quebec’s Universal Childcare System on Women’s Economic Security?’, March, submitted to the Standing Committee on the Status of Women of the House of Commons, Ottawa, pp. 8–9.

13 Fortin, P. (2017), ‘What Have Been the Effects of Quebec’s Universal Childcare System on Women’s Economic Security?’, March, submitted to the Standing Committee on the Status of Women of the House of Commons, Ottawa, p. 10.

14 Statistics Canada (2018), ‘Fertility rates and labour force participation among women in Quebec and Ontario’, last accessed 12 January 2024.

15 Bailliu, J. and Leung, D. (2023), ‘Measuring the value of women’s contribution to the Canadian economy: New insights based on recent work,’ Statistics Canada, February, last accessed 5 March 2024.

16 Record high since 1976, when this data point first became collected. See: Statistics Canada (2022), ’Labour Force Survey, November 2022’, November, last accessed 29 February 2024.

17 McGinn, K.L., Castro, M.R. and Lingo, E.L. (2018), ‘Learning from Mum: Cross-National Evidence Linking Maternal Employment and Adult Children’s Outcomes’, Work, Employment and Society, April, 33:3

18 Office for National Statistics (2023), ‘Gender pay gap in the UK: 2023‘, November, last accessed 2 February 2024.

19 Office for National Statistics (2023), ‘Gender pay gap in the UK: 2023‘, November, last accessed 2 February 2024.

20 Office for National Statistics (2023), ’Gender pay gap in the UK: 2023, November, last accessed 2 February 2024.

21 Gender pay gap refers to the differences in earnings between those identifying as male and those identifying as female.

22 Oxera (2017), ‘Social mobility and economic success‘, July, p. 3.

Related

Investing in distribution: ED3 and beyond

The National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) has published its vision for the UK’s electricity distribution network. Below, we review this in the context of Ofgem’s consultation on RIIO-ED31 and its published responses. One of the policy priorities is to ensure that the distribution network is strategically reinforced in preparation… Read More

Company valuation in post-M&A disputes—the Mahtani v Atlas Mara ruling

Post-merger and acquisition (‘post-M&A’) disputes can take many different forms, such as breach of representations and warranties, fraud and misrepresentation claims, and post-completion breach of contractual obligations. This article discusses the valuation issues in a post-completion breach case based on the ruling handed down by the Hon Mr Justice Butcher… Read More